The For-Profit College Problem

How a Promise of Opportunity Became a Pipeline to Debt—and Why It’s Back in the News

A familiar headline, a familiar story

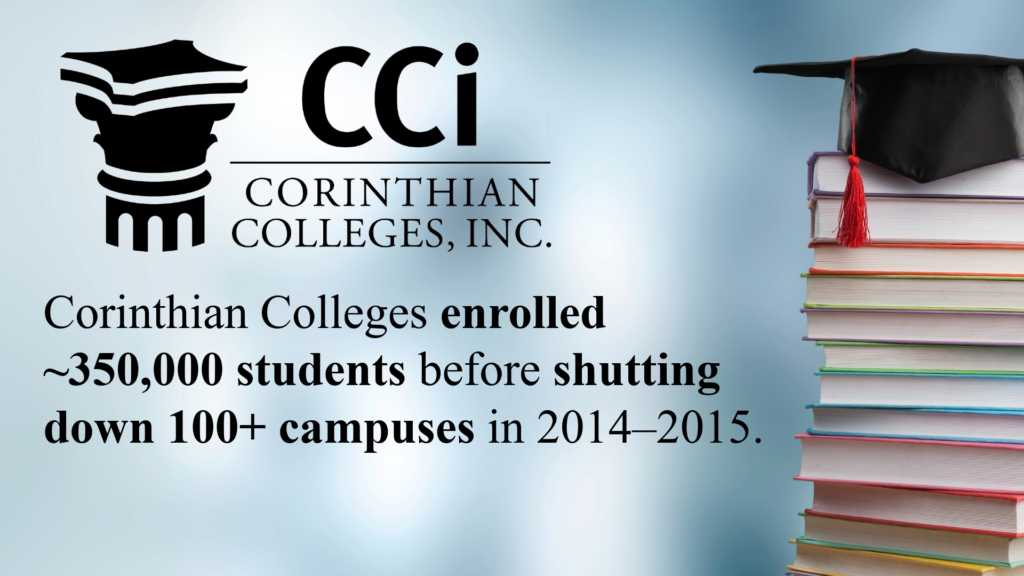

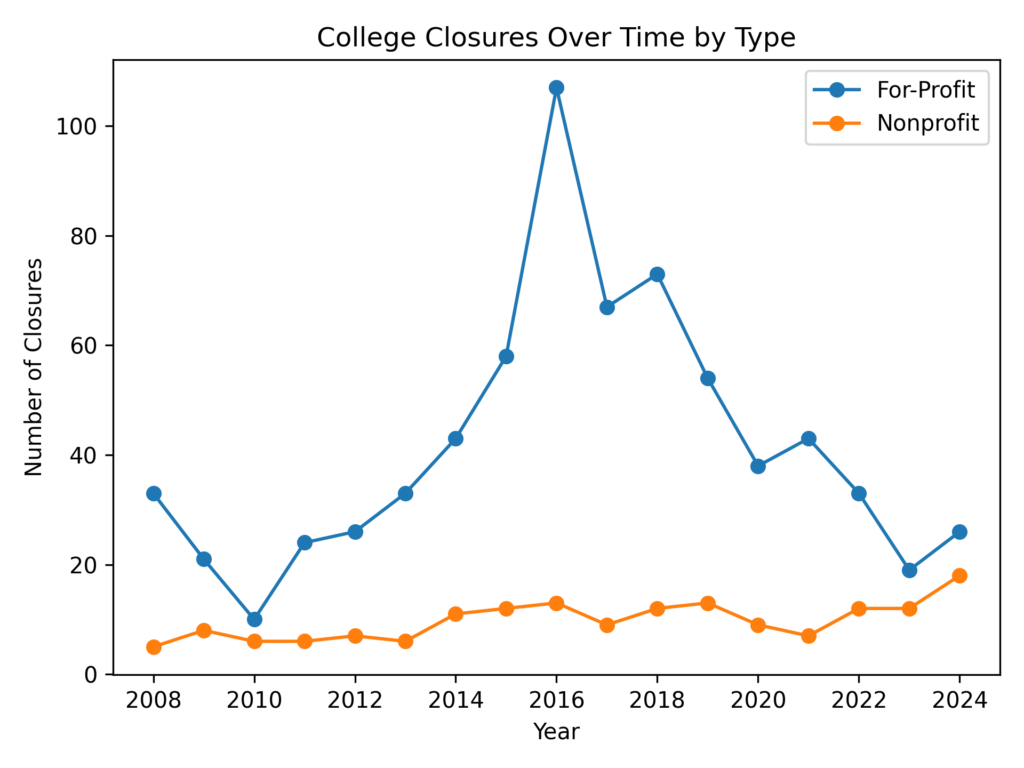

In recent months, federal and state regulators have once again turned their attention to for-profit colleges—institutions accused of misleading students about job placement, program quality, and future earnings, while leaving many graduates buried under debt. New enforcement actions, revived accountability rules, and lawsuits from state attorneys general echo a cycle that has played out repeatedly over the last two decades.

For many Americans, these stories feel déjà vu. For others—especially working adults, veterans, first-generation students, and low-income learners—they are deeply personal. Behind every policy debate is a student who believed education would be a ladder to stability, only to discover it was a trapdoor.

To understand why for-profit colleges remain such a persistent problem, we need to step back—into their origins, their business model, and the structural incentives that have repeatedly put profit ahead of students.

What is a for-profit college?

At a basic level, for-profit colleges are postsecondary institutions owned by private companies or shareholders, rather than by states (public colleges) or nonprofit boards.

Unlike traditional colleges:

- Their primary legal obligation is to generate profit

- A significant share of their revenue comes from federal student aid

- Many focus on short-term, career-oriented programs such as medical assisting, IT, criminal justice, or business administration

- Instruction is often delivered online or in accelerated formats

On paper, this sounds like innovation—flexible schedules, career focus, and access for nontraditional students. In practice, research and decades of enforcement actions show a very different reality.

Labor market outcomes are worse for for-profit students than for similar students in similar programs in other sectors. – Education Policy Research

Why they grew so fast

The modern for-profit college boom began in the 1990s and early 2000s, driven by three converging forces:

- Federal student aid expansion

As Pell Grants and federal loans became more widely available, tuition dollars followed—regardless of outcomes. - Aggressive marketing and recruitment

For-profit colleges invested heavily in advertising, lead generation, and high-pressure admissions tactics, often targeting:- Veterans and service members

- Single parents

- Unemployed workers

- Students without family college experience

- Deregulation and weak oversight

Accreditation and accountability systems were slow to adapt to corporate-owned education models.

At their peak, for-profit colleges enrolled millions of students and absorbed a disproportionate share of federal aid—despite consistently worse outcomes than public and nonprofit peers.

The business model problem

At the heart of the issue is not just poor execution, but structural incentives.

Research summarized by organizations like Public Agenda shows that many students experience the same pattern:

- Promises of quick credentials and high-paying jobs

- Little transparency about total cost and debt

- Credits that do not transfer to other schools

- Degrees that employers do not value as advertised

Meanwhile, internal documents and investigations have repeatedly revealed that some institutions spend more on marketing and shareholder returns than on instruction, faculty, or student support.

When revenue depends on enrollment volume rather than student success, outcomes become secondary.

An investigation by the Department of Education found that 72 percent of for-profit graduates with associate’s degrees were earning less than high school dropouts. – Department of Education

[Data from The Hechinger Report]

The debt-without-degree crisis

The most damaging consequence is debt.

Across multiple studies and government reviews:

- For-profit students borrow more

- They default at higher rates

- They are less likely to graduate

- Their post-college earnings are often no better—and sometimes worse—than peers without degrees

Compared to students in other sectors, students in for-profit colleges are more likely to borrow for college and less likely to repay that debt. They are also more likely to default on student loans. – Education Policy Research

This combination is especially devastating because federal student loans are rarely dischargeable in bankruptcy. Students who leave without a credential—or with a low-value one—carry the consequences for decades.

As one synthesis from Brookings Institution bluntly concluded: the system is broken, not just flawed.

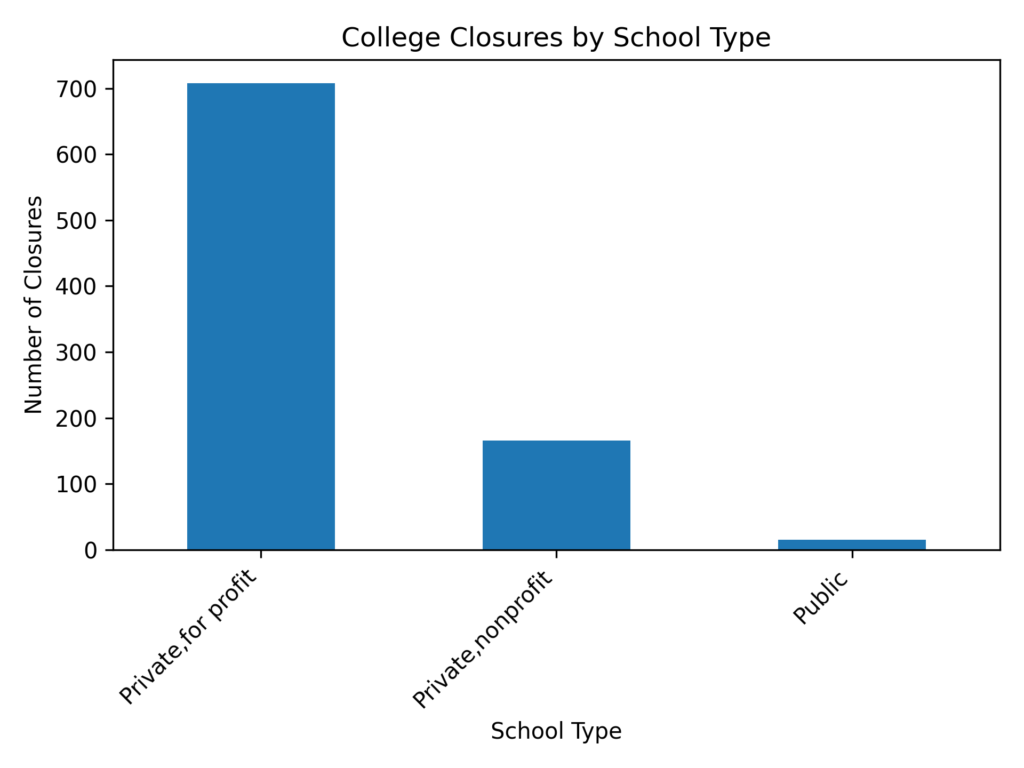

More than 60 percent of those were run by for-profit operators.

[Data from The Hechinger Report]

Why regulation keeps swinging back and forth

Successive administrations have tried—then rolled back—rules meant to curb abuse.

Key examples include:

- “Gainful employment” rules, tying access to federal aid to graduates’ debt-to-income ratios

- Restrictions on incentive-based recruiting, meant to prevent commission-driven enrollment tactics

- Enhanced disclosure requirements around costs, outcomes, and job placement

Each time oversight tightens, enrollment shrinks. Each time rules loosen, predatory behavior resurfaces.

This regulatory whiplash is one reason the problem never fully disappears.

For-profit colleges are highly dependent on Pell Grants, student loans, and the GI Bill. Regulatory changes involving eligibility for these programs have driven fluctuations in enrollment over the last several decades. Ongoing debates over the rules governing federal student aid policy will shape the sector and its students in the years to come. – Education Policy Research

The human cost behind the data

Investigative reporting and firsthand accounts—like those compiled by the Hechinger Report—reveal a consistent emotional through-line:

Students describe feeling misled, rushed, and pressured, often signing enrollment paperwork within hours of first contact. Many believed they were enrolling in something akin to a community college or public university, only to later discover stark differences in credibility and cost.

For first-generation students especially, the damage extends beyond finances. It erodes trust in education itself.

Are all for-profit colleges bad?

Not every for-profit institution is identical. Some provide legitimate training, particularly in niche or technical fields.

But system-wide data shows that as a sector, for-profit colleges:

- Produce worse outcomes at higher cost

- Depend disproportionately on taxpayer funding

- Serve vulnerable populations without delivering proportional value

That makes this not just a consumer protection issue, but a public accountability issue.

For-profit colleges disproportionately recruit and enroll students who are lower-income, women, single parents, veterans, and from traditionally marginalized groups. – Education Policy Research

What solutions actually work?

Evidence suggests several approaches make a real difference:

- Strong, consistent federal rules tied to student outcomes

- State-level enforcement and consumer protection actions

- Clear, standardized disclosures before enrollment

- Investment in community colleges and public alternatives, especially for adult learners

- Pathways for debt relief when schools mislead students

Critically, solutions work best when they focus on outcomes, not promises.

The bigger question: what is education for?

The for-profit college debate ultimately forces a deeper reckoning.

Is higher education:

- A public good, meant to expand opportunity and civic participation?

- Or a commodity, optimized for revenue extraction?

When education is treated primarily as a financial product, students become customers—and risk becomes their problem alone.

The recurring scandals around for-profit colleges are not an accident. They are the predictable result of a system that allowed public dollars to flow with minimal accountability.

Bottom line

For-profit colleges didn’t fail because a few bad actors slipped through the cracks. They failed because the incentives were wrong from the start.

As policymakers once again debate oversight, loan forgiveness, and accountability, the lesson is clear:

Access without protection is not opportunity—it’s exposure.

Until student outcomes matter more than enrollment numbers, this story will keep repeating, one headline at a time.