Inside America’s Nuclear Weapons: Aging Systems, Expensive Upgrades, and the Risks We’ve Learned to Ignore

For decades, America’s nuclear weapons arsenal has sat hidden beneath the plains—vast, aging, and dangerously overlooked. With thousands of warheads still on alert, trillion-dollar modernization underway, and talk in Washington of resuming nuclear testing for the first time in more than 30 years, the Cold War’s deadliest legacy is stirring again.

From decaying silos and cost-overrun missiles to political gridlock and renewed fallout fears, this deep dive examines how the world’s most powerful deterrent became one of its greatest risks—and why ignoring it may be the most perilous mistake of all.

In America today, the fear of nuclear annihilation has faded into the background of public consciousness.

Where once children practiced “Duck and Cover,” and government films warned of mushroom clouds, most citizens now worry about cyberattacks, pandemics, or even AI—while the nation’s most powerful weapons quietly age in silos and submarines around the world.

Yet the danger didn’t disappear. Instead, the U.S. maintains an enormous, increasingly brittle nuclear arsenal at tremendous cost and under troubling human-systems strain.

A Triad of Power — Nuclear Weapons Then and Now

As of early 2025, the United States is estimated to have around 3,700 nuclear warheads in its military stockpile—with about 1,770 deployed warheads ready on missiles and bombers.

These nuclear weapons are distributed across the three legs of the so-called nuclear “triad”: land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) in Wyoming, Montana, and North Dakota; sea-based submarines armed with ballistic missiles; and strategic bombers capable of delivering nuclear gravity bombs or cruise missiles.

While the Cold War peaked at over 30,000 warheads in the U.S. arsenal, the numbers have been dramatically reduced since. But a reduction in quantity has not necessarily meant a less hazardous system. Many delivery systems remain Cold War vintage, human-factor errors persist, and modernization efforts are enormous in scope and cost.

Cracks in the Foundation

In recent years, the U.S. nuclear enterprise has revealed troubling signs of wear. A 2024 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report described aging infrastructure, cyber vulnerabilities, and poor morale among missile crews.

For example, although the Air Force officially retired many floppy-disk-based control computers years ago, other legacy systems are still in operation. Meanwhile, the forthcoming Sentinel ICBM program—intended to replace the decades-old Minuteman III—has exceeded cost and schedule thresholds and required a major replan.

Operational readiness raises further concerns. Across missile bases in the Northern Plains states, inspections have flagged unacceptable performance, officers have been disciplined for cheating on proficiency tests, and routine maintenance issues such as failing doors or unsecured silos have been reported.

Each of these failures compounds risk in a system where mistakes can trigger catastrophic outcomes.

Testing the Bomb: Legacy, Fallout, and What It Means Today

From the ten-thousand-foot flash over the desert to the coral-reef blasts in the Pacific, nuclear testing helped shape modern warfare even as it scarred communities and fostered an enduring legacy of risk.

The U.S. conducted more than 1,000 nuclear explosive tests between 1945 and 1992, according to comprehensive datasets. The first atomic detonation, codenamed Trinity Test (July 16, 1945), ushered in the nuclear age. After World War II, the U.S. conducted massive atmospheric and underwater tests—famously at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands during the Operation Castle series of 1954.

One bomb, Castle Bravo, yielded 15 megatonnes—10 million tons of sand, coral, and water vaporized, a fallout cloud 100 miles wide, and long-term health and environmental damage for nearby atoll populations. By the time the U.S. entered a moratorium in 1992, it had tested a vast arsenal of weapons under a variety of conditions.

The consequences of those tests were far from theoretical.

Research published in 2023 reconstructed radionuclide deposition from U.S. atmospheric tests in New Mexico and Nevada, revealing measurable contamination across the contiguous U.S. — and raising fresh questions about human health impacts.

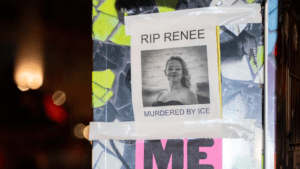

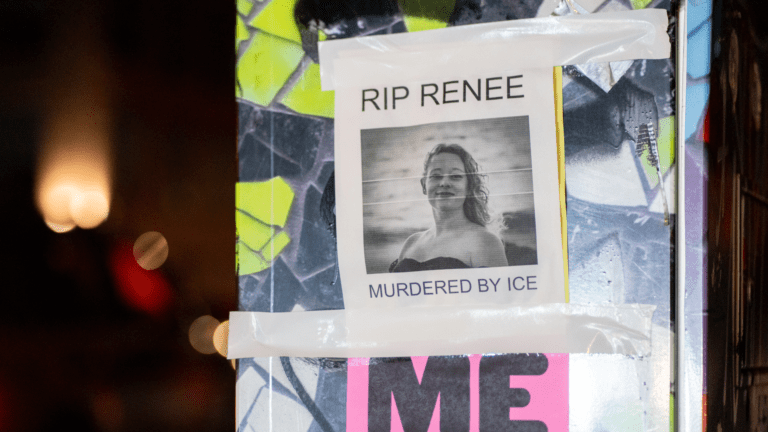

Meanwhile, Indigenous communities, Pacific atoll residents, and downwind populations in states like Utah and Nevada continue to live with the legacy of testing.

Since the early 1990s, the U.S. has maintained a policy of not conducting full-scale nuclear detonations. That remained the practice even as other nuclear powers slowed but did not always halt their own testing.

In 2024–25, a dramatic shift emerged: senior U.S. officials and commentators argued for resuming explosive testing. Then in October 2025, the president announced a directive to “immediately” resume testing—a move that triggered warnings from the Comprehensive Nuclear‑Test‑Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) that any explosive test would undermine global non-proliferation, sending shock waves through arms-control regimes.

The argument for testing: Testing isn’t simply an engineering exercise—it is a signal of capability, reliability, and deterrence. Proponents argue that without real nuclear weapons explosive testing, adversaries might doubt the effectiveness of U.S. warheads.

But opponents warn of several cascading risks:

- Resuming nuclear weapons tests breaks decades of norm-building established by the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty and the still-unratified 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty.

- It could trigger a new arms race, encouraging Russia, China, or others to resume tests and thereby destabilize international security.

- Technical challenges remain: even after years of computer simulation, detonations carry the risk of unpredictable yield outcomes, safety failures, or environmental contamination.

The testing question highlights the broader vulnerabilities of the arsenal. For a system already stressed by aging silos, cyber-risks, and personnel issues, asking whether we can safely test large nuclear weapons—and then control them—raises hard questions.

The legacy of earlier tests reminds us that the consequences of miscalculation extend far beyond boardrooms: they imprint on landscapes, communities, and public health.

Why So Many Nuclear Weapons?

Why keep thousands of warheads if they’re hard to manage and carry immense risk? The answer lies in politics, strategy, and inertia.

First, from a strategic standpoint, many military and defense officials argue that the U.S. must maintain credible deterrence against Russia and China. This means having a force that’s large, ready, and technologically advanced.

Second, at the political level, many missile bases sit in states whose economies lean on the nuclear mission—Montana, North Dakota, Wyoming, and Nebraska have elected officials who vigorously protect silo operations, even when the Pentagon suggests scaling back.

Third, modernizing or reducing the arsenal is expensive in its own right. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that current plans to operate, sustain, and modernize U.S. nuclear forces will cost approximately $946 billion through 2034. This figure reflects ballooning costs, program delays, and expanded scope.

In short, the system we have is expensive, unwieldy, and difficult to change.

Dollars, Risk, and Oversight

The sheer scale of spending on nuclear forces invites scrutiny.

When nuclear weapons cost more to maintain than some parts of the domestic safety net, questions arise about value and risk. According to GAO and other oversight entities, many modernization programs have suffered cost overruns and schedule slips.

Yet the risk isn’t only in dollars—it’s in human and system reliability. Historical examples show how fragile the deterrent system can be.

In 1961, a U.S. B-52 broke apart over North Carolina and dropped two bombs, one of which was armed and nearly detonated. In 1980, a socket dropped down a missile silo in Arkansas and nearly triggered a catastrophe. More recently, in 2007, six live nuclear-armed cruise missiles were mistakenly loaded onto a bomber and left unguarded for 36 hours.

Each incident shows how small errors or contingency factors can escalate into a national catastrophe.

Why the Public Doesn’t Care

Despite the stakes, public attention to nuclear weapons has waned.

In the 1980s, protests against nuclear buildup brought large crowds to central parks; today, congressional hearings on nuclear security draw attendance low enough to be described as comparable to a weekday open-mic night. People no longer see mushroom clouds looming overhead, so complacency creeps in.

That lack of urgency creates a dangerous mismatch: an arsenal that demands vigilance is being managed in an era of distraction.

What’s At Stake

The U.S. nuclear deterrent depends not simply on warheads, but on the people, systems, and processes behind them. A delivery system fails if the command chain misfires, a silo door sticks, or a fatigued crew member misses a cue. Modern nuclear weapons don’t reduce the need for human reliability—they actually increase the complexity of the system, and complexity often means more failure points.

Each near-miss in the past should serve as a warning, not reassurance. The margin for error remains slender.

Looking Ahead: What To Watch

Over the coming years, four issues merit particular attention:

- Sentinel ICBM and Triad Recapitalization: The rollout of the new Sentinel ICBM has slipped beyond its original timetable, now expected post-2035. Its cost overruns and delays will influence future options for the ICBM force.

- Arms Control Erosion: With the last major nuclear arms treaty (New START) set to expire in February 2026 and no follow-on agreement imminent, we risk entering an unconstrained arms race.

- Cyber and AI Threats: As nuclear command and control systems modernize, their digital vulnerabilities expand. Ensuring cybersecurity for the most powerful weapons on the planet is essential in the age of AI-enabled threats.

- Public Oversight and Reform: Congress and the public must decide whether the nuclear enterprise should continue expanding or be reorganized for sustainability and safety. The rising cost and the aging infrastructure cannot be ignored indefinitely.

The Bottom Line

America’s nuclear arsenal remains the ultimate paradox: the most powerful force ever built, intended to prevent war—yet vulnerable to system decay, human error, and strategic drift. The weapons themselves may rarely be used, but the infrastructure supporting them must function nearly flawlessly.

If history teaches us one lesson, it is that complacency is humanity’s greatest foe. The next accident may not be spectacular—it might just begin with a stuck door, a flawed test, or a miswired alert.

Deterrence remains vital. But maintaining it demands far more than warheads and silos. It demands competence, vigilance, and the political will to reform what is increasingly fragile.

In the end, the greatest risk may not be from the weapons we imagine—they may already be in our worst oversight.

Further reading on U.S. nuclear weapons & arms control:

- Further reading on U.S. nuclear forces & arms control – Reuters, April 30, 2025, by Jonathan Landay

- With only one nuclear arms pact left between the US and Russia, a new arms race is possible – AP News, August 6, 2025, by Emma Burrows

- China stockpiling nuclear warheads at fastest rate globally, new research shows – The Guardian, June 17, 2025, by Amy Hawkins

- Nuclear risks grow as new arms race looms—new SIPRI Yearbook out now – Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, June 16, 2025

- Status of World Nuclear Forces – Federation of American Scientists, March 26, 2025, by Hans Kristensen & Matt Korda & Eliana Johns & Mackenzie Knight-Boyle & Kate Kohn