Medicare Advantage, Explained: What It Is, How It Works, and Why It Often Fails the People Who Need It Most

Medicare Advantage (MA) has become one of the most heavily marketed and widely misunderstood parts of the U.S. healthcare system. It’s advertised as a low-cost, benefit-rich version of Medicare, but the reality is far more complex—and often troubling for the people it claims to serve.

TLDR:

What this is about. This article breaks down Medicare Advantage (MA)—a privately administered alternative to traditional Medicare—using specific facts, examples, and figures.

Why now. Medicare’s open enrollment runs October 15 – December 7 each year, a period saturated with celebrity-fronted TV ads (Joe Namath, William Shatner, Meredith Vieira, Jimmie “JJ” Walker, etc.). In one recent season, over 500,000 of these spots aired—about 8,000 per day—many blurring the line between “Medicare” and “Medicare Advantage.”

The key distinction. Traditional Medicare is administered by the federal government. Medicare Advantage (Part C) is different: the government pays private insurers to administer beneficiaries’ coverage.

Enrollment trend. More than half of eligible beneficiaries are now in Medicare Advantage, with projections approaching two-thirds by 2034.

Expert warning in one line. “The best candidate for Medicare Advantage is someone who’s healthy. We see trouble when someone gets sick.” And people do get sick—especially in the older population Medicare serves.

Understanding the Context

Each year, from October 15 to December 7, Medicare’s open enrollment period floods television screens with celebrity-endorsed ads from Joe Namath, William Shatner, and Meredith Vieira urging seniors to “call now” for “extra benefits.” In one recent season, more than 500,000 of these ads aired—about 8,000 every day—many blurring the line between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage (MA).

Despite sharing the word “Medicare,” the two are fundamentally different. Traditional Medicare is run directly by the federal government, while Medicare Advantage (Part C) is administered by private insurance companies that receive government payments to manage beneficiaries’ care. The distinction is critical but often lost in the advertising.

Over half of all Medicare beneficiaries are now enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, a number projected to rise to two-thirds by 2034. Yet, experts warn the system primarily benefits those who are healthy. As one put it, “The best candidate for Medicare Advantage is someone who’s healthy. We see trouble when someone gets sick.”

How Medicare Works—And Where MA Fits In

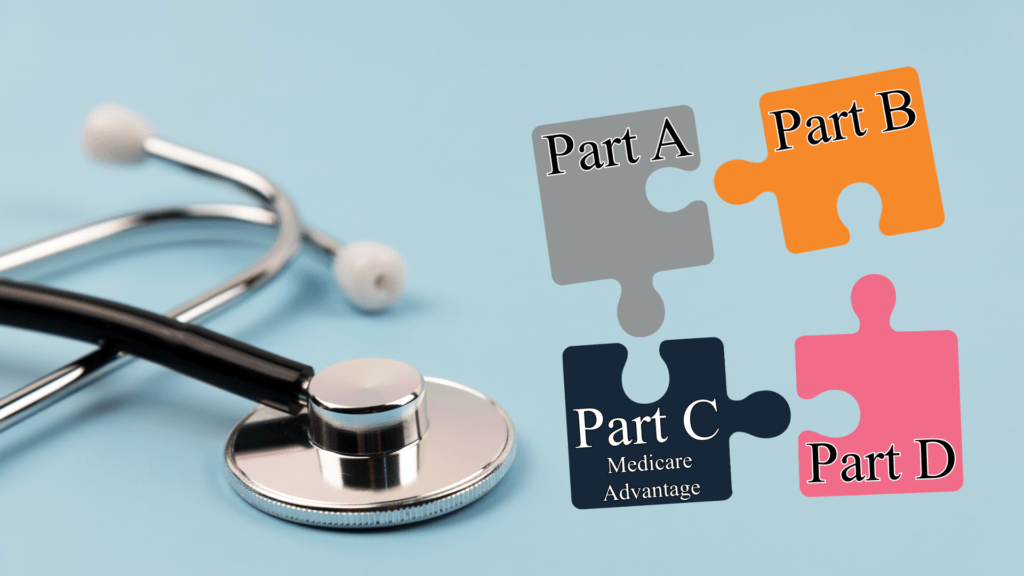

Medicare is divided into four parts:

- Part A covers hospital and inpatient care. Funded through payroll taxes, it typically carries no premium after age 65.

- Part B covers outpatient and doctor visits. Beneficiaries pay a monthly premium—usually deducted from Social Security—which covers 80% of costs. The remaining 20% can be offset by purchasing Medigap, a supplemental plan that often costs $200 or more per month.

- Part D provides prescription drug coverage through a separate monthly premium.

- Part C, or Medicare Advantage, bundles the above into a single, privately administered plan. It often includes extras like dental, vision, hearing, or even grocery debit cards. Over three-quarters of enrollees pay no additional premium beyond their standard Medicare deduction.

These benefits, coupled with aggressive advertising highlighting traditional Medicare’s 20% coverage gap, make Medicare Advantage appear to be an “all-in-one” solution. But the simplicity is deceptive.

The Promise vs. the Reality

Medicare Advantage (MA) was created under the belief that competition among private insurers would lower costs and improve choice. Instead, a 2022 report found that over the past 18 years, MA has cost taxpayers $591 billion more than traditional Medicare. The reason: the structure of the program incentivizes profit, not savings.

How the Payment System Encourages Abuse

Under traditional Medicare, providers are paid per treatment. Under Medicare Advantage, insurers are paid a fixed amount per member each year—adjusted for how “sick” each member is, based on diagnosis codes. The sicker the patient appears, the more money the insurer receives. This system, known as risk adjustment, has led to widespread abuse through a process called upcoding—the artificial inflation of diagnoses.

An investigation found $50 billion in excess Medicare payments over three years tied to conditions added by insurers. Patients often had no idea they’d been coded for diseases they didn’t have, and in many cases, there was no record of treatment.

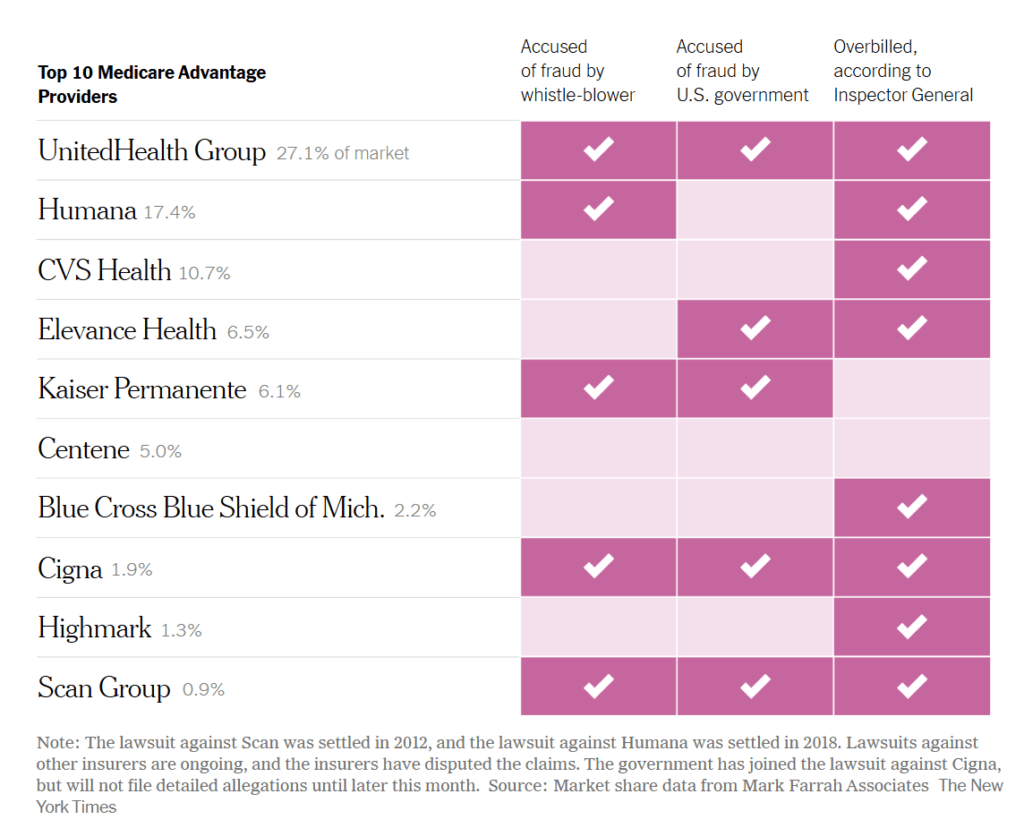

In 2022, 8 of the 10 largest Medicare Advantage insurers were found to have inflated bills, and 4 of the 5 largest faced federal fraud lawsuits over upcoding.

Source: Market share data from Mark Farrah Associates

The New York Times

One common strategy is through so-called “home visits.” Companies like UnitedHealthcare advertise them as free in-home wellness checks, but investigations revealed they were used to pad patient charts with expensive diagnoses. Each hour-long visit generated an average of $1,800 in additional government payments.

In one striking example, UnitedHealthcare’s software prompted nurses to code patients with “secondary hyperaldosteronism,” a rare hormonal disorder, without requiring lab confirmation. Between 2016 and 2019, the company reportedly added this diagnosis nearly 250,000 times, resulting in $450 million in extra government payments. A Department of Justice investigation into the company’s billing practices is ongoing.

Another insurer, Independent Health, paid $98 million to settle allegations that its internal policy coded both spouses with the same illness—leading, infamously, to a woman being listed as having prostate cancer.

What Patients Experience

When you’re healthy, Medicare Advantage feels like a good deal: low or zero premiums, gym memberships, and limited dental or vision benefits. But once you get sick, the problems begin.

Network restrictions are a major issue. Traditional Medicare is accepted by most providers nationwide. Medicare Advantage plans, however, limit enrollees to in-network doctors within a specific service area—and networks can change without warning. One cancer patient who had been treated at Boston’s Dana-Farber Cancer Institute for years was suddenly told she could no longer go there because, while her doctor was in-network, the building itself was out-of-network.

Even finding a covered doctor can be challenging. Reviews show that 30% to 60% of provider directories contain inaccurate or outdated information. One diabetic patient searching for an endocrinologist discovered that two of the four listings in his area were actually grocery store pharmacies.

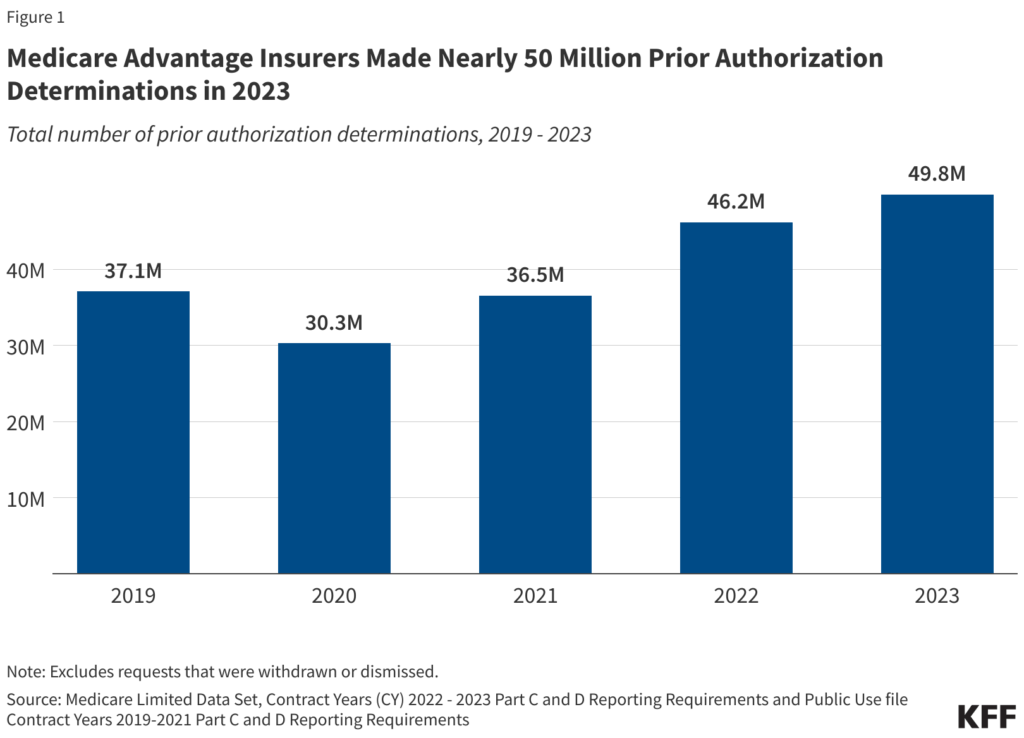

Then there’s the barrier of prior authorizations—permissions required from insurers before receiving treatment. Traditional Medicare rarely requires them; nearly all Medicare Advantage plans do. Doctors describe hours of phone calls and faxes for approvals, with some requests delayed or denied outright. Millions of these authorizations are denied each year.

The consequences can be devastating. After brain surgery, patient Gary Bent needed long-term rehab. His UnitedHealthcare plan approved only short-term care. His family won a few appeals but ultimately lost when the company denied further coverage. He was discharged early with a fever and neck pain, returned to the ER within 11 hours with meningitis, and died the following winter. His wife said fighting for his coverage added to his suffering.

The Ripple Effects on Hospitals

Hospitals, especially in rural areas, are also feeling the strain. Constant denials and delayed payments erode finances and force difficult choices. In Holly Springs, Mississippi, Alliance Healthcare had to close its entire geriatric psychiatry unit, with its CEO saying the facility “died the last few years with Medicare Advantage.”

Nationwide, nearly 20% of health systems in 2023 stopped accepting at least one Medicare Advantage plan due to administrative costs and underpayment.

The “Trap Door” Effect: Why It’s Hard to Leave

Many seniors believe they can simply switch back to traditional Medicare if they become unhappy with an Advantage plan. But that’s often not true.

When first enrolling in Medicare, anyone can buy a Medigap policy to cover the 20% of Part B costs not paid by Medicare. After joining Medicare Advantage, however, most states allow insurers to reject Medigap applicants or charge higher rates based on pre-existing conditions. As a result, many enrollees find themselves stuck in Medicare Advantage, unable to afford switching back.

The Industry’s Defense—and Independent Findings

Insurance companies argue their plans save money and improve outcomes. Yet when independent experts reviewed the industry’s own studies, they found fundamental flaws, biased data, and exaggerated conclusions, describing the results as an “alternate reality.”

In short, while Medicare Advantage performs well in marketing materials, the evidence shows it costs more, delivers less flexibility, and often denies care when patients need it most.

The Policy Debate

The problems in Medicare Advantage point to deeper issues in America’s fragmented healthcare system. Many experts argue for single-payer healthcare, or at least a stronger, simpler traditional Medicare that removes the need for private intermediaries.

Fixes could include expanding traditional Medicare to cover the 20% cost gap that drives seniors to private plans and renaming Medicare Advantage altogether—since, as critics point out, it isn’t Medicare in the sense most people understand.

What Consumers Should Know

If you can afford it, experts recommend enrolling in traditional Medicare with a Medigap plan and Part D drug coverage.

If you’re considering Medicare Advantage, proceed carefully. Verify which doctors and hospitals are actually covered, understand that networks can change, and prepare for potential prior authorization hurdles.

Avoid calling numbers from television ads—brokers are often paid higher commissions for steering callers into MA plans. Instead, contact your State Health Insurance Assistance Program (SHIP) for unbiased guidance tailored to your state.

The Bottom Line

Medicare Advantage is not truly Medicare—it’s private insurance paid for with public funds. It has cost taxpayers nearly $600 billion more, while often leaving patients facing narrower networks, delayed care, and denials when they become ill.

The structure of the system rewards over-diagnosing on paper while under-delivering care in practice, and hospitals, particularly in rural areas, are bearing the brunt. Once enrolled, many seniors can’t easily leave.

The evidence is clear: if the goal is affordable, reliable healthcare for America’s seniors, strengthening traditional Medicare—not expanding private versions of it—would be the real advantage.

Key Takeaways

- Medicare Advantage ≠ Medicare. It’s private insurance paid with public dollars.

- Costs are higher for taxpayers (≈ $591B more over 18 years) while care often becomes harder to access when you’re sick.

- Payment rules reward upcoding, not necessarily better care.

- Patients face narrow networks, error-filled directories, and prior authorization hurdles.

- Hospitals—especially rural—are financially strained; some drop Medicare Advantage plans; some close units.

- Once enrolled, many can’t easily leave Medicare Advantage due to Medigap underwriting later on.

- Policy direction: strengthen and simplify traditional Medicare; at minimum, stop calling it “Medicare Advantage.”