The Cloud Is America’s New Critical Infrastructure. Three Companies Run Most of It.

It is 2:07 a.m. and the “incident” channel is a wall of red.

A hospital’s patient portal is timing out. A payroll system is stuck mid-run. A small city’s 311 requests will not load. A startup’s entire product is returning errors because a single authentication call is failing upstream. None of these organizations share a CEO, a board, or a budget. But, increasingly, they share something more consequential: the same invisible landlord.

We call it “the cloud,” as if it is weather. It is not. It is concrete, cables, power, software, contracts, and a small number of corporate control rooms.

And right now, the digital infrastructure landscape is drifting toward a dangerous truth: the modern economy runs on a stack controlled by three hyperscalers, and the incentives that made cloud computing fast and cheap are also pushing us into a consolidation trap.

That is the core tension of the modern digital economy: we have deliberately centralized enormous amounts of computing into a small number of global platforms because centralization is efficient, powerful, and secure when done well. But the same centralization raises a harder question that is not about any single outage or any single company.

If most of the world’s “compute” lives in a few places, what happens when the world needs choices?

The Big Three and the Shape of the Market

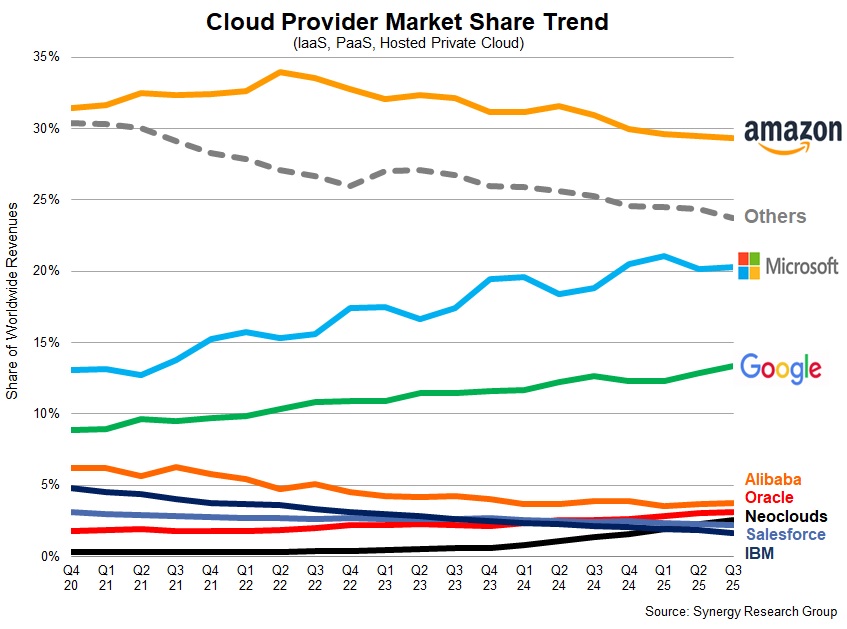

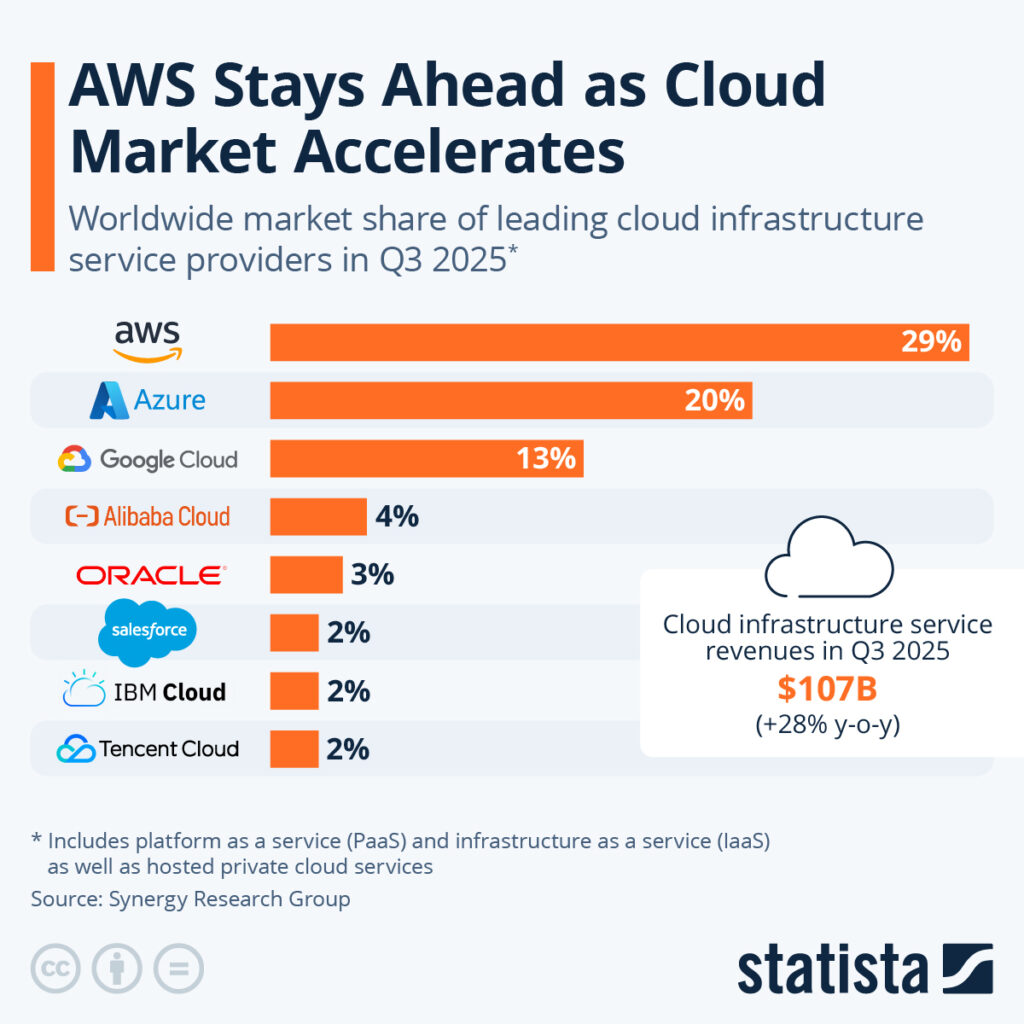

The “big three” hyperscalers, Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud, collectively take over two-thirds of global cloud infrastructure spending, and that share has inched upward over time.

There are plenty of other providers. Oracle, IBM, Alibaba Cloud, regional clouds, and a growing set of specialized “neo-clouds.” But when big enterprises, governments, universities, or hospitals decide where their core systems will run, the short list is usually the same three.

This is the part many people miss: cloud consolidation does not have to look like a single monopoly to create monopoly-like outcomes. When three firms sit beneath huge portions of the internet’s day-to-day operations, they can function like a shared chokepoint even while competing fiercely with each other.

Competition at the top can coexist with fragility underneath.

What “hyperscaler” really means

A hyperscaler is not just “a big cloud company.” It is a company that can do all of this at once, at global scale:

- Build and operate massive data center fleets.

- Buy hardware, networking gear, and electricity at industrial bargaining power.

- Offer thousands of services on top of raw computing: databases, AI platforms, security tooling, analytics, identity systems, developer pipelines.

- Keep launching new capabilities fast enough that customers feel behind if they are not on that platform.

This is why “cloud” is no longer only a cheaper server. It is an operating system for the economy.

Why Consolidation Keeps Winning

Consolidation is not an accident. It is an engineered outcome of cloud economics.

1) Scale advantages are real, and they compound

Hyperscalers buy compute, chips, bandwidth, and electricity at a scale that is hard for smaller providers to match. Their data centers are not just large, they are optimized factories. Once a provider gets big, it gets cheaper to get bigger.

2) Customers do not just buy compute. They buy ecosystems.

This is where consolidation concerns get sharper.

If your cloud provider is also your office suite provider, your identity provider, your endpoint security platform, your developer platform, and your AI assistant vendor, then “cloud choice” is not a clean, standalone decision. It becomes a bundle decision, where leaving one part of the bundle can create downstream costs elsewhere.

That is why regulators have started treating cloud not just as a tech market, but as a foundational market that other markets sit on top of.

3) Lock-in is not a side effect. It is a business strategy.

Lock-in can be technical (rewriting workloads). It can be contractual (egress fees, committed spend). And it can be legalistic and licensing-based.

In the United Kingdom, the Competition and Markets Authority’s cloud market investigation concluded that competition is not working well, and it singled out issues that make switching harder, including Microsoft licensing practices.

Even if you love your provider, a market where leaving is punitive is not a healthy market. It is a market where power accumulates.

4) AI accelerates the “rich get richer” loop

AI is compute-hungry, data-hungry, and capital-hungry. The hyperscalers are not just selling the infrastructure for AI. They are often financially entangled with the AI developers and model providers that drive demand for that infrastructure.

The FTC has been investigating and reporting on major AI partnerships and investments involving big cloud providers, focusing on control rights and exclusivity-like structures.

AI is not only a new product category. It is a consolidation engine.

The Consolidation Concern Most People Underestimate: Dependency

Worry #1: Competition.

If three providers dominate, do prices rise, innovation slow, and smaller entrants get squeezed out?

Worry #2: National and economic resilience.

If core public and private services depend on a narrow stack, do we create systemic risk? Do we end up with “too big to fail” infrastructure, where the practical ability to diversify is limited?

When one bank fails, regulators worry about contagion. We should start thinking about the cloud the same way.

A large outage at a hyperscaler is not “a tech problem.” It is a multi-sector disruption. Recent reporting around AWS outages and public-sector dependence has pushed this concern into the open.

Even without outages, concentration creates quieter risks:

- Security monoculture risk: one vulnerability class repeats across thousands of customers.

- Operational dependency: critical services become hostage to one vendor’s incident response timeline.

- Policy leverage: a small number of firms become de facto rulemakers for how identity, data, and AI are deployed.

- Innovation tax: startups build for the ecosystems that control distribution, not the architectures that might be best.

If you want to see where this goes, look at how governments are reacting. The EU has been assessing whether AWS and Azure merit extra scrutiny under the Digital Markets Act framework, reflecting rising concern about cloud gatekeeping.

This is not paranoia. It is a recognition that the cloud has crossed a threshold: it looks and behaves less like a product and more like essential infrastructure.

The Counterargument, Taken Seriously

The strongest argument against intervention is simple: hyperscalers earned their position by building reliable services, lowering costs, and accelerating innovation.

There is truth there. Cloud has made it possible for a two-person team to deploy globally, for researchers to run workloads that once required supercomputers, and for organizations to scale without buying their own hardware. That is not trivial.

And regulators can absolutely overreach. Heavy-handed rules could raise costs, slow security improvements, or create compliance burdens that only the biggest firms can afford, which would be an irony-rich way to deepen the very consolidation we are trying to address.

But here is the problem: doing nothing is also an intervention. It is an intervention on behalf of lock-in.

When exit is expensive, competition becomes theater. When a market’s structure produces systemic risk, “trust us” is not a resilience plan.

If The Cloud Is Becoming a Utility. We Should Regulate It Like One.

We do not need to punish success. We need to reduce dependency risk and restore credible exit options.

That means regulators and large buyers should focus less on breaking up companies and more on breaking up captivity.

What that looks like in practice

1) Portability and interoperability requirements that actually bite

Not “nice to have” APIs. Concrete expectations for workload portability, identity federation, logging formats, and data export that reduce switching costs over time.

2) Egress fee and switching friction scrutiny

If leaving a provider costs a fortune, the market is not competitive. Make providers justify pricing structures that function as exit penalties.

3) Licensing and bundling guardrails

If an incumbent can use dominance in one software category to tilt the playing field in cloud, regulators should treat it as a competition problem, not a pricing quirk. The CMA’s focus on licensing practices shows exactly why.

4) Public-sector procurement should diversify by design

Governments should avoid single-provider default choices for critical services unless there is a compelling, documented reason. If the public sector becomes a captive anchor tenant, concentration becomes self-fulfilling.

5) Resilience expectations for critical cloud service providers

Not every cloud vendor needs to be regulated like a utility. But when a provider becomes a critical dependency for essential services, baseline resilience and transparency obligations are reasonable.

The Bottom Line

Cloud consolidation is not just “big tech getting bigger.” It is the quiet redesign of the economy’s foundations.

When three companies sit under the software that runs hospitals, schools, small businesses, and governments, we should stop treating cloud choice as a purely private purchasing decision. It is also a collective risk decision.

The goal is not to make the cloud smaller. The goal is to make the cloud safer to depend on by ensuring that the exit doors are real, the switching costs are not punitive, and the market cannot drift into a handful of unavoidable chokepoints.

If we wait until the next major outage, breach cascade, or AI-driven lock-in wave forces a political reaction, we will get rushed policy and bad policy.

Let’s call it what it is: cloud is essential infrastructure now, and concentration should be managed like essential infrastructure, too.