Redistricting and Gerrymandering: How Drawing Lines Shapes—and Distorts—American Democracy

Why the fight over political maps is reshaping elections, empowering some voters, silencing others, and determining who holds power in America.

Every decade, the United States redraws its political maps. It sounds simple—update districts after the census so that each one contains roughly the same number of people. But in practice, this process is one of the most powerful, least visible forces in American politics. It determines who represents us, which communities have a voice, and sometimes even which party controls Congress.

In 2025 and 2026, redistricting is back in the headlines because courts in multiple states are reviewing or overturning maps passed after the 2020 Census, reshaping the playing field for the 2026 midterms. Newly elected leaders are attempting to revise districts to strengthen their party before the next election cycle, while the Supreme Court’s recent rulings continue to narrow what is considered illegal gerrymandering. As both parties maneuver for advantage, voters across the country face the reality that lines on paper may matter just as much as votes in a ballot box.

To understand why, we must look at how redistricting works, where gerrymandering came from, how its use has transformed over centuries, and why the fight over drawing maps remains one of the central structural battles in American democracy.

Where Redistricting Came From — And Why It Exists at All

The framers of the Constitution never used the word “redistricting,” but they did require that representation be based on population, measured every ten years. As people moved, cities grew, and the country expanded, the districts had to be adjusted. The idea was simple: each person should have roughly equal representation.

By the mid-1800s, Congress required states to use single-member districts (one representative per district), which made map-drawing a recurring political responsibility. Over time, population growth, immigration, industrialization, and suburbanization made the redistricting process essential—and increasingly ripe for manipulation.

Redistricting, when done fairly, updates districts to reflect real communities and a changing nation. But when politicians draw the lines to benefit themselves or their party, the practice becomes something else entirely: gerrymandering.

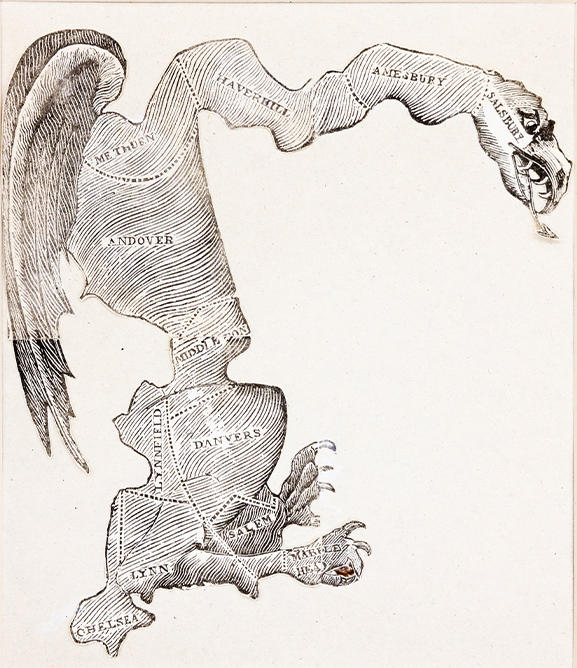

Gerrymandering: The American Political Shortcut

Gerrymandering began as soon as redistricting began. In 1812, Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry approved a state senate district so contorted that critics joked it resembled a salamander. They called it a “Gerry-mander,” and the name stuck.

But the practice did not begin with Gerry and has never stopped. Gerrymandering means drawing districts in a way that creates unfair advantages—cracking some voters into many districts to dilute their influence, or packing them into one district so they cannot influence others. The results can be dramatic: elections may appear competitive, but the maps themselves guarantee a predetermined outcome.

With modern political data and software, gerrymandering has evolved from a crude art into a precise science. Map-drawers can now target specific neighborhoods, blocks, households, or demographic traits with extraordinary accuracy. This ability to finely tailor districts allows lawmakers to choose their voters instead of voters choosing their representatives.

Redistricting vs. Gerrymandering: One Necessary, One Corrupted

Redistricting is required, routine, and legally mandated.

Gerrymandering is the manipulation of that process for political gain.

Not all oddly shaped districts are gerrymandered. Communities rarely live in neat squares; some maps are intentionally shaped to keep distinctive communities together or to comply with the Voting Rights Act by preserving minority representation. Redistricting scholars note that compactness, competitiveness, and community-of-interest boundaries often conflict, and it is physically impossible to satisfy all three perfectly.

But while distortion alone does not equal wrongdoing, intentional manipulation does. And American history is filled with examples of both parties exploiting the power to draw maps—including some that reshaped national politics for a decade or more.

Why Politicians Gerrymander

There are three main motivations:

1. Partisan Advantage

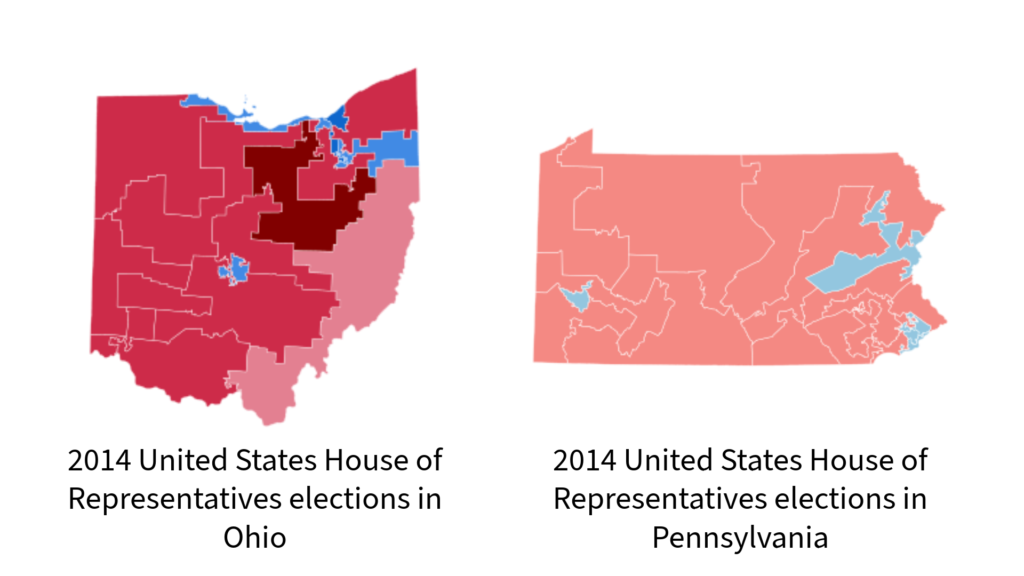

The most common form today. Parties draw maps to maximize seats even when their statewide vote share does not justify it. For example:

- Pennsylvania (2014): Democrats won 44% of votes for the U.S. House but secured only 5 of 18 seats.

- Ohio (2014): Democrats won about 40% of votes but only 4 of 16 seats.

These gaps are possible when maps crack or pack voters with mathematical precision.

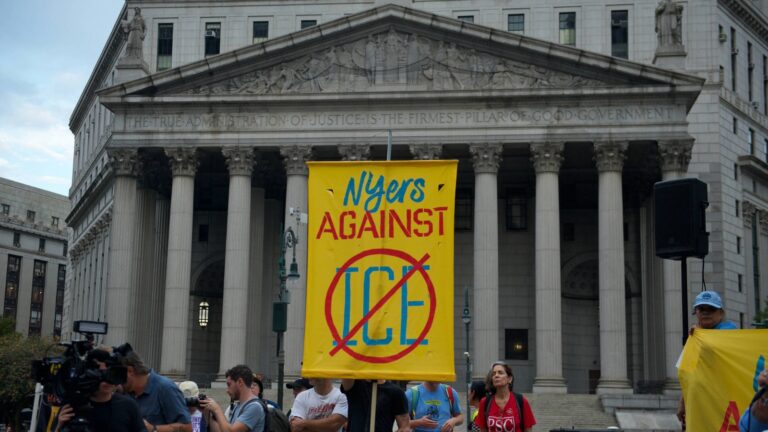

2. Racial Gerrymandering

Manipulating lines to weaken or dilute the political power of racial groups is illegal under the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Courts still regularly strike down such maps, but the boundaries between unlawful racial gerrymandering and permissible partisan gerrymandering have grown increasingly blurry—especially when race and political affiliation overlap.

3. Incumbent Protection

Parties sometimes carve districts to protect sitting officials—even from their own party challengers. In one notable example*, a state assembly map was drawn so precisely that the home block of a potential challenger was carved out of the district entirely. Both parties have engaged in this kind of defensive map-making.

*Hakeem Jeffries ran for NY State Assembly in 2002; the new map drawn by Democrats carved out the block where he lived from Assembly District 57.

How Gerrymandering Works: Packing, Cracking, and Data

The two classic techniques are:

- Packing: Concentrate opposition voters into as few districts as possible.

- Cracking: Split them across many districts so they cannot form a majority anywhere.

Because modern algorithms can simulate thousands of map variants, gerrymandering has become extraordinarily effective. In some states, computers can draw lines weaving around individual blocks to favor one party by single percentage points—enough to flip districts without drawing attention.

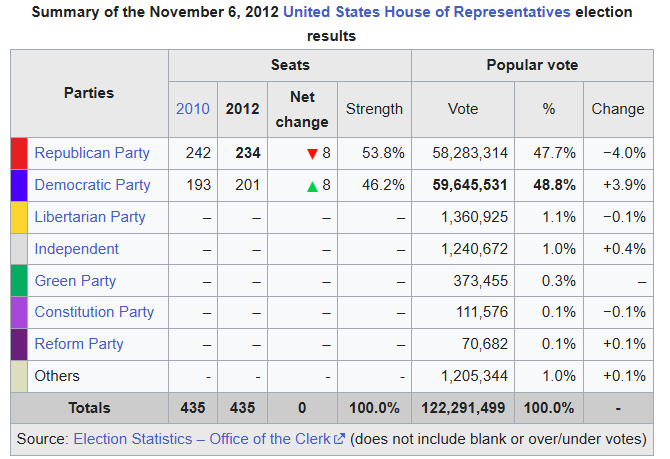

This precision has helped parties secure disproportionate representation. After the 2010 wave election, for instance, a coordinated strategy known as the Redistricting Majority Project invested heavily in state legislative races that determined who would draw the maps. The result: even when a party won more nationwide House votes in 2012, the other party won more seats due to the maps drawn two years before.*

*Although Democratic candidates received a nationwide plurality of more than 1.4 million votes (1.1%) in the aggregated vote totals from all House elections, the Republican Party won a 33-seat advantage in seats, thus retaining its House majority by 17 seats

The Legal Rules: What Is Allowed, What Is Not

U.S. law draws a sharp line:

- Racial gerrymandering with discriminatory intent is unconstitutional and illegal.

- Partisan gerrymandering, however, is largely permitted.

The Supreme Court has ruled in recent years—most notably in Rucho v. Common Cause (2019)—that partisan gerrymandering claims are “nonjusticiable,” meaning federal courts cannot decide them. States may regulate partisan gerrymandering themselves, but the federal judiciary will not intervene.

Key rules that are enforced:

- Districts must be contiguous.

- Districts must follow the principle of equal population.

- States cannot intentionally dilute minority voting power.

- States may consider—but are not required to prioritize—compactness or competitiveness.

This mix of strict rules and wide discretion is why some bizarrely shaped districts survive legal scrutiny while simple-looking ones are struck down.

How Gerrymandering Has Changed Over Time

19th and early 20th centuries

Maps were hand-drawn, population data was imprecise, and manipulation was crude but common.

Mid-20th century

Supreme Court rulings such as Baker v. Carr (1962) and Reynolds v. Sims (1964) established the principle of “one person, one vote,” forcing states to equalize district populations.

Civil Rights Era

The Voting Rights Act added protections for minority voters—but also led to legal battles over whether maps that grouped minorities together were empowering or segregating them.

Computerization (1990s–2000s)

Parties acquired sophisticated voter files, allowing precision gerrymandering.

Big Data Era (2010s–2020s)

Mapping software advanced to the point where line-drawing could predict election outcomes with striking accuracy. Lawsuits surged across the country, but partisan gerrymanders increasingly survived federal court review.

Today (2025–2026)

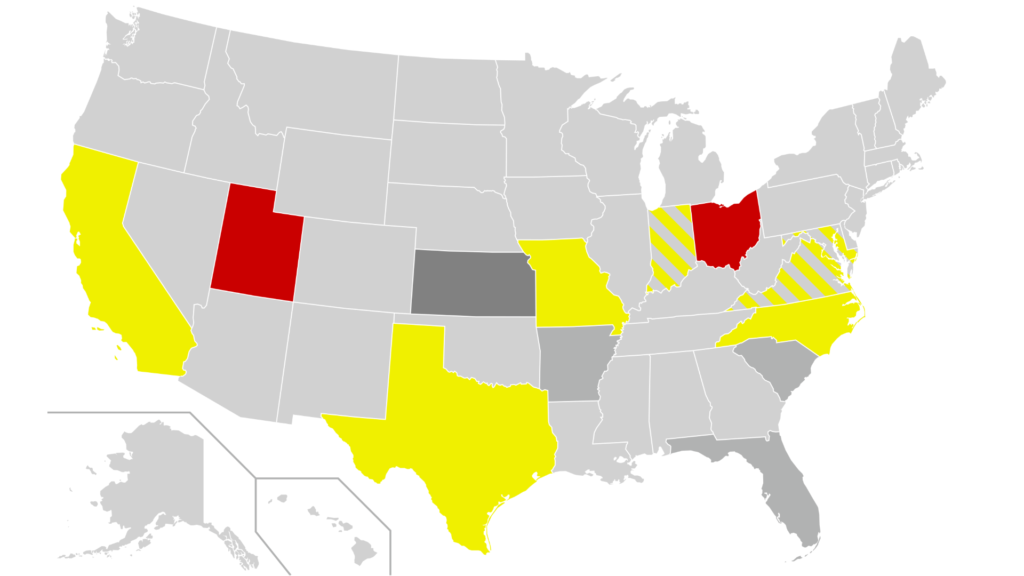

States continue revising their maps mid-decade as courts order redraws and new majorities seek political advantage. According to 2025–2026 redistricting projections, several states—including North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and New York—will have altered maps by 2026, shaping the next midterm elections.

Planned or not yet in effect (Dark Grey): Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, New York, Virginia, and Maryland

Unsuccessfully attempted (Dark Grey): Arkansas and South Carolina

Why It Matters: The Impact on Elections and Governance

Gerrymandering affects nearly every part of American political life:

Distorted Representation

Parties can win a majority of statewide votes yet a minority of seats—undermining the principle of equal representation.

Uncompetitive Elections

Safe districts remove incentives for compromise, increasing polarization. The real contest happens in the primary rather than the general election.

Voter Disillusionment

When outcomes feel predetermined, turnout declines and trust erodes.

Policy Extremes

Lawmakers in safe seats often worry more about primary challenges than general elections, rewarding ideological purity over coalition-building.

National Consequences

Because House control can hinge on a handful of engineered districts, gerrymandering can influence national policy, budgets, and even constitutional debates.

How Gerrymandering Is Being Used Today

In the 2025–2026 redistricting fight:

- Some states are expanding partisan gerrymanders after recent court rulings gave them greater freedom.

- Other states are facing court-ordered redraws due to racial gerrymandering claims.

- Parties are using gerrymandering to counter demographic change, especially as voter preferences shift in key suburban battlegrounds.

- Incumbents continue carving districts to avoid internal challengers.

NPR’s 2025 reporting notes that both parties are aggressively seeking map advantages ahead of a highly competitive 2026 midterm cycle, with some states expected to swing several seats purely due to new district lines.

Why Gerrymandering Persists

Despite public frustration, gerrymandering endures because:

- The Constitution leaves most redistricting power to the states.

- Many politicians benefit from the system and have no incentive to reform it.

- Federal courts will not regulate partisan gerrymandering.

- Voters are residentially clustered—especially Democrats in urban areas—making proportional maps more difficult even without intentional manipulation.

- Reform requires changing state laws or constitutions, which can be politically difficult.

As a result, the system favors those already in charge of drawing the lines.

How We Could Fix It — And What Solutions Exist

Several reforms have been proposed and tested:

1. Independent Redistricting Commissions

Used in states like California, Michigan, and Arizona, these citizen-led bodies aim to remove direct partisan influence. Research shows they create more competitive and representative maps, though critics note that “perfect neutrality” is impossible.

2. Clearer Federal Rules

Congress could set uniform standards for compactness, competitiveness, or partisan fairness—but such reforms have repeatedly stalled.

3. State-Level Reforms

Some states have enacted anti-gerrymandering amendments or court standards defining what counts as excessive partisan bias.

4. Proportional Representation

An alternative electoral system—such as multi-member districts with ranked-choice voting—could reduce the incentive to manipulate boundaries. But it would require federal legislation and major political will.

5. Enhanced Transparency

Public map-drawing software and open hearings can expose manipulation and build trust.

No reform is perfect, but nearly every expert agrees on one point: the current system—where politicians draw maps that decide their own political futures—creates structural distortions incompatible with democratic accountability.

The Bottom Line

Gerrymandering is not new, and it is not partisan in any consistent direction. Both parties have used it whenever they’ve held the pen. But its impact has grown dramatically with modern technology, polarized politics, and court rulings that leave partisan map-drawing largely unchecked.

At its core, redistricting is supposed to reflect how the country changes. Gerrymandering, however, reflects how those who hold power try to keep it.

As the 2026 midterms approach, new maps across key states will again shape the balance of the House, sway state legislatures, and influence whose voices are amplified—or silenced. And while many proposed reforms could improve the system, their adoption depends on political will that has not yet materialized widely.

Until that changes, the battle over who draws the lines will remain one of the most consequential—and least understood—fights in American democracy.