Iran in 2026: The currency crash, the uranium clock, and the thin line between a deal and a war

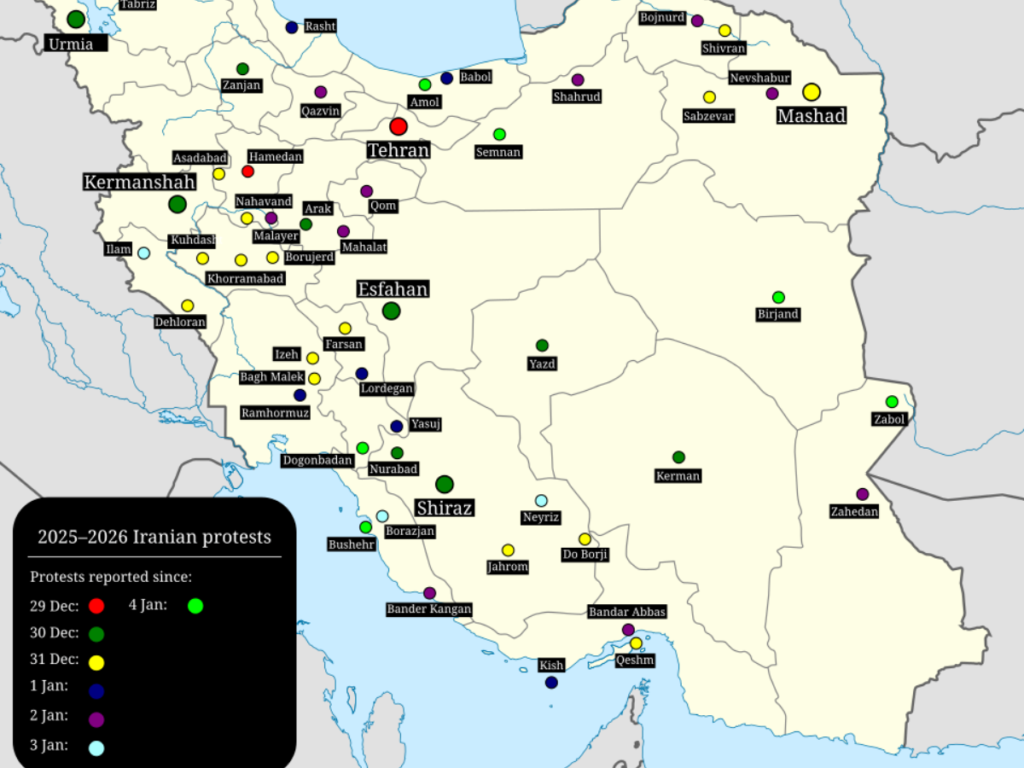

In Abdanan, a Kurdish town in Iran’s Ilam province, people came to a cemetery to mark the dead. Witnesses and activists said security forces opened fire on the crowd. Video shared from the scene showed people scattering as gunfire cracked through chants of “Death to the dictator,” a slogan aimed at Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

That is the atmosphere Iran is living in right now: mourning ceremonies that turn into flashpoints, protests that keep resurfacing, and a state response that rights groups and witnesses describe as increasingly lethal. Reuters reporting last month described deaths that did not stop with protesters, including bystanders, and cited competing tallies from an Iranian official and a rights group that said thousands had been killed, with many more cases under review. Human Rights Watch has also said Iran’s security forces carried out mass killings after nationwide protests escalated in early January, while communications restrictions made the scale harder to verify from the outside.

The protests themselves are not occurring in a vacuum. They sit on top of an economic pressure cooker: currency declines, high prices, sanctions, and the feeling among many Iranians that the system cannot or will not deliver a stable life. When money stops feeling real, politics gets more combustible, because every day becomes a referendum on whether the state is still in control.

But Iran’s domestic crackdown is unfolding at the same time as the country’s most dangerous international standoff. Tehran’s nuclear program has become the fuse everyone is watching. Iran has amassed highly enriched uranium up to 60 percent, and the IAEA chief has warned that time is short to lock in constraints before another military escalation makes oversight even harder.

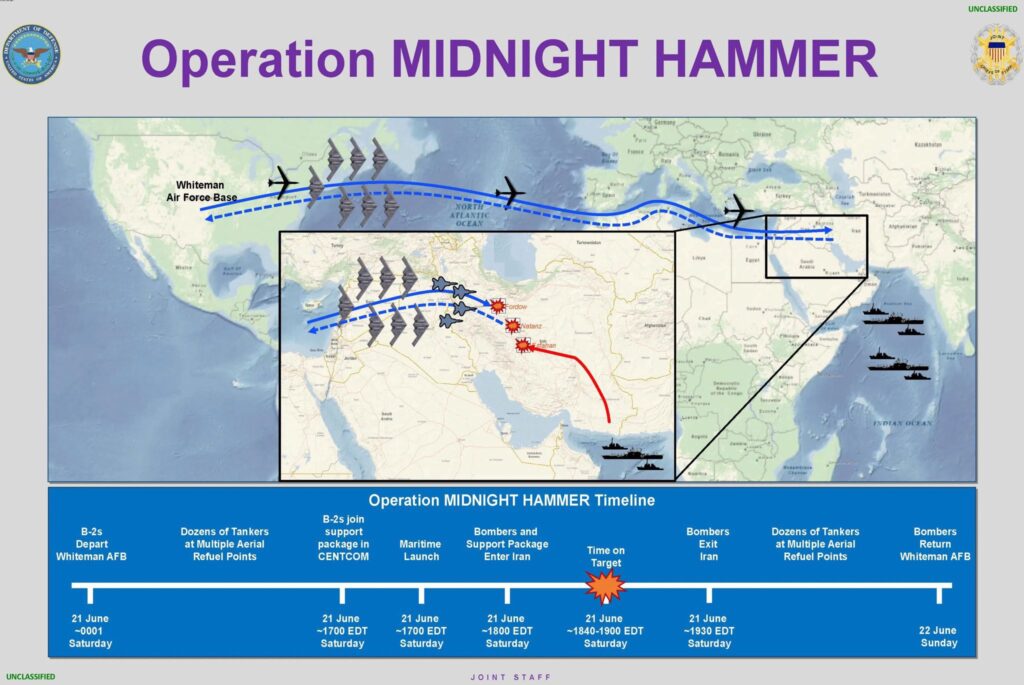

That is why the negotiations feel less like diplomacy and more like a countdown. On Friday, Reuters reported that Iran is preparing a counterproposal as indirect talks continue, even as President Donald Trump publicly weighs limited strikes to force an agreement, with U.S. officials describing advanced planning and options that range from targeted attacks to more expansive aims. Earlier Reuters reporting described the same internal logic more bluntly: the idea that striking security forces or leaders could be used to try to reignite protests after the January crackdown.

So Iran is boxed in from two directions at once. Inside the country, the streets keep demanding change, and the state keeps showing it will meet that demand with bullets. Outside the country, uranium enrichment keeps compressing timelines and shrinking room for error, while Washington signals that military action is not a hypothetical.

And that leaves the questions that make this moment feel like a sealed room with the temperature rising: If the protests swell again, does the regime double down, or does something in the system crack? If a nuclear deal is floated, is it strong enough to matter and fast enough to stop the spiral? If strikes come, do they delay a program or detonate a region? And in the middle of all of it, what does Iran’s leadership do when it is trying to survive both its own public and a world that is running out of patience?

The pressure cooker economy

Iran’s economy has been battered for years by sanctions, corruption and mismanagement, capital flight, and the hard reality of trying to run a modern country while being partially cut off from the global financial system. Oil still matters because oil still pays the bills. But that lifeline is under strain again.

Reuters has reported repeated episodes of sharp currency declines and the domestic anger they help ignite, including protests tied to the rial’s dwindling value and the rising cost of living.

When Iran’s currency hits new lows, it does more than bruise national pride. It accelerates a cycle: households rush to convert savings into dollars or gold, merchants raise prices to protect themselves from the next drop, and the government’s credibility erodes because no one believes tomorrow’s exchange rate will resemble today’s. That dynamic can become politically destabilizing even when the state retains strong security control.

Meanwhile, the “macro” outlook is bleak. The IMF’s country data shows weak projected growth for 2026. And the World Bank has described Iran’s recent growth as heavily tied to oil recovery, while sanctions and geopolitics continue to hang over the economy.

This matters because sanctions relief is not just a diplomatic prize for Tehran. It is one of the few levers that could plausibly slow the economic spiral without a fundamental restructuring of governance and corruption. And that reality is why nuclear negotiations keep coming back, even after years of breakdowns and recriminations.

The uranium clock and why 60% is the number that scares everyone

Iran insists it does not seek a nuclear weapon. But it has built something that looks, to many outside observers, like a “latent” weapons capability: the ability to move quickly if it ever chose to cross the line.

The core technical issue is enrichment.

- Most civilian nuclear power programs use low-enriched uranium.

- Iran has enriched uranium up to 60%, which is not weapons-grade but is close enough that the remaining technical distance to roughly 90% can shrink dramatically. Arms Control Association notes that 60% has no practical civilian application and underscores how much “reversibility” has already been lost because knowledge gained cannot be unlearned.

- A Congressional Research Service explainer lays out another important point often lost in cable-news shouting: enriching uranium is not the same as possessing a deliverable nuclear weapon. Weaponization involves additional steps, including developing a workable design and a functioning detonation system, and producing and shaping uranium metal components.

Still, the enrichment level matters because it changes timelines.

The Institute for Science and International Security has analyzed IAEA reporting and estimated that Iran’s stockpile and centrifuge configuration could allow very rapid production of enough weapon-grade uranium for multiple weapons if enrichment were pushed further.

That is the “breakout time” fear. Not that a bomb appears overnight, but that the world could wake up to a reality where the material hurdle is largely gone, leaving only the weaponization hurdle and the political decision.

The strikes, the uncertainty, and the problem of “you can’t bomb knowledge”

Another reason the tension feels sharp now is that Iran’s nuclear infrastructure has already been attacked.

Reuters published an explainer on the status of Iran’s main nuclear facilities following strikes, noting that while enrichment had reached up to 60% before the attacks, the IAEA’s assessment was that much of the nuclear material likely remained, even if verification was difficult and some damage occurred.

This is the brutal logic of the nuclear file: airstrikes can destroy machines, buildings, and power supplies, but they cannot erase expertise. If a country retains personnel, know-how, and enough of its supply chain, it may be able to rebuild, disperse, and harden.

That reality makes diplomacy feel both more urgent and more fragile. Urgent, because timelines can shrink. Fragile, because each escalation incentivizes Iran to move more activity underground, reduce transparency, and treat inspectors as liabilities rather than guardrails.

The talks and the ultimatum: diplomacy with a gun on the table

This week’s moment is defined by negotiations and an overt threat.

Reporting from the Financial Times and The Guardian describes a U.S. deadline-driven push for a deal alongside a significant U.S. military buildup in the region, with the president signaling that decisions could come within days. Al Jazeera has reported on the Geneva talks and the wider context of pressure and counterpressure, including military signaling and regional posturing.

The International Atomic Energy Agency’s director general, Rafael Grossi, has been publicly warning about time and risk, urging a deal and emphasizing the proliferation danger posed by highly enriched uranium that remains in Iran’s possession.

There are two overlapping negotiating fights inside “the negotiations”:

- The nuclear limits question

How much enrichment is Iran allowed to do, at what purity, with what stockpile caps, and under what inspection regime? Arms Control Association’s status tracking makes clear how far Iran has moved since the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA and why rolling it back is not a simple rewind. - The sanctions relief question

Iran wants meaningful relief it can feel in oil sales, banking channels, and investment. The United States wants constraints that last and can be verified. If sanctions relief is weak or easily reversible, Tehran’s incentive collapses. If constraints are weak or unverifiable, Washington’s incentive collapses.

In other words: each side wants the other to go first, and each side fears getting locked into the worst of both worlds.

Why the U.S. keeps talking about military intervention, and why that threat is risky

The military option is not new. It is the shadow that has followed every round of talks for two decades. But the present situation raises the stakes because of the combination of advanced enrichment, damaged sites, and regional tension.

The “case” for military action, as hawks frame it, is straightforward: if diplomacy fails and Iran can shorten the path to weapons-grade material, strikes could delay a dash and re-establish deterrence.

The “case” against it is also straightforward: military action could trigger retaliation against U.S. forces and partners, escalate through proxy networks, disrupt shipping and energy markets, and push Iran to expel inspectors and rebuild with fewer constraints. The CFR’s conflict tracker documents how proxy dynamics and regional escalations have repeatedly pulled the U.S. and Iran toward confrontation even when neither side claims to want a full war.

The oil market is already reacting to the risk. Reuters has reported crude prices moving on expectations about U.S.-Iran tensions and the possibility of disruption around the Strait of Hormuz, a key artery for global oil flows.

This is where the economic story snaps back into view: Iran is both vulnerable to sanctions and capable of causing global pain if conflict closes shipping lanes or raises insurance and security costs. That leverage is part of why the standoff is so hard to resolve cleanly.

The missing piece in most discussions: what Iran’s leaders are trying to survive

It is tempting to treat Tehran as a single actor with a single objective. In reality, the Iranian system is a coalition of power centers: elected institutions with limited authority, unelected institutions with enormous authority, security forces, clerical networks, economic interests, and factions that rise and fall.

Under intense economic strain, leaders often do one of two things:

- Seek a deal to buy time and calm markets.

- Or escalate externally to unify internally, justify repression, and shift blame.

Iran’s domestic economic distress, currency volatility, and the legitimacy challenge that comes with both are not side plots. They are the stage on which the nuclear drama is playing.

Where this goes next

Barring a sudden breakthrough, there are three realistic near-term paths.

1) A limited deal, not a grand bargain

This might look like capped enrichment, tighter monitoring, partial sanctions relief, and phased compliance. It would not solve everything, but it could slow the clock and lower the temperature.

2) No deal, continued pressure, and a “managed escalation”

More sanctions, more military deployments, more covert activity, and intermittent strikes. This path often becomes the default because it postpones political pain in Washington and Tehran while increasing long-term risk.

3) A strike and a cascading retaliation cycle

If diplomacy collapses and leaders decide credibility requires action, the region could slide into a wider conflict that neither side can fully control.

None of these outcomes is preordained. But Iran’s collapsing currency and its advanced enrichment program are pushing events toward decision points faster than in prior years.

The bottom line

The world keeps returning to the Iran question because it is not just about centrifuges. It is about what happens when a sanctioned, economically strained state believes nuclear capability is the ultimate insurance policy, while the United States believes allowing that capability invites a regional arms race and a permanent crisis.

For ordinary Iranians, the story begins with prices and paychecks. For diplomats, it begins with verification and timelines. For military planners, it begins with targets and retaliation.

But it ends in the same place: whether a deal can be strong enough to slow the uranium clock, real enough to ease the economic pressure, and credible enough that neither side feels forced to prove something the hard way.