Why You Should Join a Club to Help Save Democracy

Loneliness is rising—and so is the cost of living without a “we.” As clubs, halls, and local groups fade, everyday hardships isolate us, trust erodes, and democracy grows brittle—but the simplest repair may be the oldest: show up, join, and belong again.

On paper, America is more connected than ever. In reality, a lot of people are living the same quiet sentence: I don’t really belong anywhere anymore.

In early December, The Washington Post reported on a new AARP survey of adults 45 and older: 40% were classified as lonely in 2025, up from 35% in 2018. Many of the people who felt lonely had felt that way for more than six years. The reasons weren’t dramatic. They were mundane and human: a divorce, a parent’s illness, a job change, grief, money stress, moving, caregiving—life doing what life does.

Now connect that to a different scene.

In October, Stars and Stripes reported on the slow fade of places that used to function as community anchors—Veterans of Foreign Wars halls, American Legion posts, Disabled American Veterans (DAV) chapters. One veteran described them as “stale beer and stories from the past,” a blunt way of saying: the institution isn’t pulling in the next generation. Membership numbers tell the same story: DAV membership fell below 1 million members in 2024, and the VFW’s membership is roughly half what it was 30 years ago, according to reporting.

Here’s the line between the two stories:

When the places that absorb life’s shocks disappear—clubs, chapters, leagues, congregations, neighborhood groups—ordinary hardships don’t just hurt. They isolate. And when hardship isolates, loneliness stops being a feeling and becomes a condition: fewer people to lean on, fewer chances to be seen, fewer “third places” where you can show up as yourself and be expected.

Robert Putnam gave this condition a civic name: a decline in social capital—the trust, reciprocity, and networks that make a society feel like a “we” instead of a crowd of strangers.

And when the “we” thins out, democracy doesn’t explode. It corrodes.

For over 100 years, Arch Social has been a fixture of Black Baltimore’s civil society. Many scholars have asserted that Arch Social is the oldest known, continuously operating African American men’s club in the United States.

[Wikimedia Commons, Preservation Maryland]

What a club really produces (and why that matters)

A club can be a bowling league, a volunteer squad, a PTA, a union local, a Rotary chapter, a book club, a running group, a choir, a neighborhood association—anything that meets regularly and asks something of you.

The activity is the wrapper. The real product is:

- repeated contact (you see people again and again)

- shared norms (how we treat each other here)

- obligation (you matter because you’re counted on)

- practice (disagreeing without exile; leading without dominating)

Two centuries ago, Alexis de Tocqueville noticed Americans’ instinct to form associations or clubs for everything—from serious causes to small undertakings—and warned that if citizens don’t learn “the art of uniting,” tyranny grows easier.

Putnam’s modern update is simple: those clubs are not decoration. They are civic infrastructure.

What clubs have done—when they’re strong

Sometimes the impact is local and immediate: a volunteer crew that keeps a food pantry staffed, a veterans hall that raises money for families, a neighborhood group that turns a neglected park into a place kids can safely play.

Sometimes it’s global.

Rotary’s decades-long campaign against polio is one of the cleanest examples of what organized membership can do at scale. Rotary says it has helped immunize billions of children and contributed billions of dollars, working with partners through the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. The GPEI says polio incidence has decreased by 99.9% since 1988.

That’s the hidden superpower of clubs: they turn goodwill (which is plentiful) into capacity (which is rare).

[Wikimedia Commons, Herbert Mulford]

The problem: the “joining” began to fall—and the timing wasn’t random

Putnam’s 1995 essay, “Bowling Alone,” describes a long rise in American civic connectedness into the early-to-mid 20th century, then a plateau, and then a meaningful decline beginning around the late 1960s and 1970s.

Why then?

Because society was changing in ways that quietly made “joining” harder and less habitual:

- Life got more scheduled and less communal. Work patterns, commuting, and the sense of constant time pressure leave fewer “free” evenings for meetings. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that full-time employed people average 8.4 hours of work on weekdays they work.

- Entertainment moved indoors. Putnam argued television didn’t just fill time—it displaced the time that used to belong to civic life.

- Geography changed. Car-centered sprawl and mobility reduced the frictionless neighborliness of denser communities—more people you drive past, fewer you actually know.

- Civic life changed shape. Theda Skocpol argued that America shifted from local, chapter-based membership organizations toward professionalized advocacy groups with fewer rooted, face-to-face ties—“associations without members.”

When joining stops being the default, belonging becomes something you have to hunt for. And when belonging becomes hard to find, many people simply go without.

[Wikimedia Commons, Zubick Art Studio]

The downward trend into today—and what it’s doing to us

Here’s what the decline looks like when it reaches the present:

Loneliness becomes widespread—and persistent

AARP’s data suggests tens of millions of older Americans are living with sustained loneliness, and the story notes practical barriers to reconnecting: low confidence, fear of rejection, and lack of time.

Health costs rise

The U.S. Surgeon General’s 2023 advisory on social connection frames loneliness and social isolation as serious health risks—linked to higher risks of premature death and disease, and comparable in effect size to major risk factors like smoking and excessive drinking.

Trust drops

Pew Research Center reports that the share of Americans who say “most people can be trusted” fell from 46% in 1972 to 34% in 2018 (General Social Survey trend).

When you don’t regularly live alongside people who are different from you, “other people” become an abstraction—and abstractions are easy to distrust.

Civic life turns episodic

The Census Bureau reports that while volunteering has rebounded from pandemic lows, the average hours per volunteer dropped from 96.5 (2017) to 70 (2023) per year—consistent with more “episodic” volunteering.

Not worse intentions—just thinner commitment. Less of the “I’m on the roster.”

Civic norms get brittle

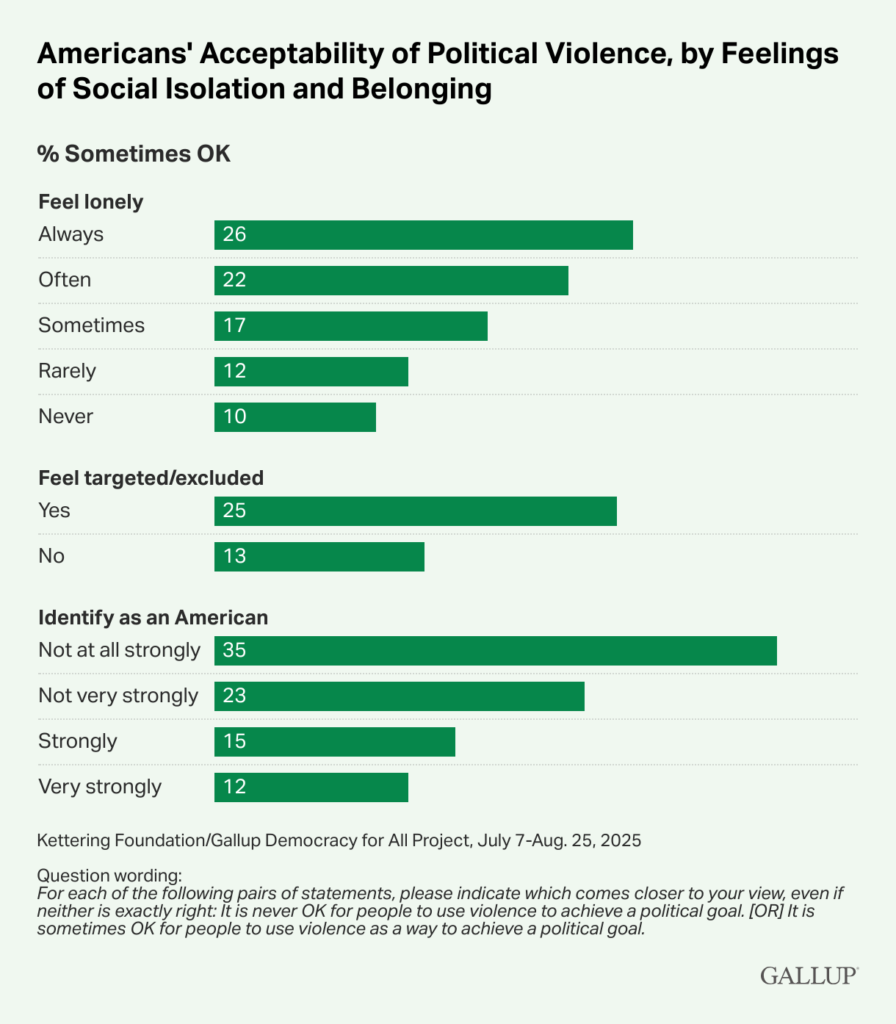

A December 2025 Gallup analysis found that among some groups—especially young men who feel lonely—acceptance of political violence (“sometimes OK”) is much higher than among peers who don’t feel lonely.

This is the most direct democratic consequence of social disconnection: when people feel unseen and untethered, some become more willing to burn the system down rather than repair it.

Why solutions are hard (even when the problem is obvious)

If loneliness were solved by information, the AARP report wouldn’t exist.

The obstacles are built into modern life:

- It’s easier to consume community than to build it. Screens offer frictionless company without obligation.

- Joining requires risk. You can’t guarantee you’ll be welcomed. (AARP’s reporting captures that fear.)

- Many legacy institutions feel like museums. Veterans organizations are wrestling openly with relevance, culture, and who the space is “for.”

- We’ve lost the habit. Putnam’s core point: social capital is built by repetition. When the repetition ends, rebuilding feels awkward—like starting the gym after years away.

That’s why the fix can’t be a slogan. It has to be a new era of joining.

The other side of the curve: before membership fell, it rose—and we can learn from that

Putnam’s story isn’t only decline. It’s also invention.

America’s great associational boom in the early 1900s wasn’t nostalgia—it was adaptation. Industrialization and urbanization disrupted older patterns of rural life; people responded by building new organizations that matched the new country they were living in.

Skocpol’s work similarly highlights how chapter-based, federated organizations once knit Americans together across towns and states—creating local identity and national purpose.

When big social change broke old bonds, civic entrepreneurship built new ones. The bonds strengthened democracy because they taught millions of ordinary people how to cooperate, argue, vote, lead meetings, and solve problems together.

That pattern—disruption → reinvention—is available again.

The upswing: what it could look like now

In the last couple of years, “joining” has re-entered the culture as a serious idea. The documentary Join or Die—explicitly inspired by Putnam—frames club membership as a democratic imperative, not a hobby.

And there are early signs of motion: formal volunteering has rebounded post-pandemic, even if sustained hours remain down.

So what would a real upswing require?

Not more opinions. More rooms.

- rooms where you are expected

- rooms where you are useful

- rooms where you encounter people you didn’t handpick

- rooms where disagreement doesn’t equal exile

Or in Putnam’s language: more bridging social capital—ties that cross age, class, party, and background, the exact ties democracy needs to stay elastic under stress.

The goal: join a club for you—and for all of us

Join a club because your life will likely be healthier if you do. The former Surgeon General is clear that social connection is not a luxury; it’s a protective factor.

But join for the larger reason, too:

Because democracy is not only ballots and courts and laws. Democracy is a daily muscle—trained in small rooms, on weeknights, by people who are tired but show up anyway.

A club teaches you something the internet can’t reliably teach: how to be part of a “we” without surrendering your “me.” How to commit. How to repair. How to disagree and keep the relationship.

That’s why this isn’t self-help.

It’s civic duty.

So pick something. Anything that meets again next week. Put your name on the list. Be the person who returns. Not because your community owes you belonging—though it does—but because your country needs citizens who still know how to belong to one another.

Not “ask what your country can do for you.”

Ask: Where can I show up—reliably enough—that other people start to feel less alone in this country?

That’s how the “we” comes back.