Tariffs in the United States

TL;DR

Tariffs are taxes on imported goods imposed by governments. In the U.S., they have been used historically both as a source of revenue and as a tool of protectionism. Over time, the U.S. shifted from high tariffs toward trade liberalization, with modern tariffs now deployed more selectively (e.g. trade remedies, national security). Key turning points include the Tariff Act of 1789, the Fordney‑McCumber and Smoot‑Hawley acts, and the shift to reciprocal trade authority in the 1930s. Contemporary tariffs can raise consumer prices, provoke retaliation, and distort trade.

What It Is

A tariff is a tax or duty that a government charges on goods entering (imports) or, less commonly, leaving (exports) its borders. It raises the cost of foreign goods, making them less competitive relative to domestically produced goods.

Why It Matters

- Tariffs shape trade flows, consumer prices, and diplomatic relations.

- They remain one of the most visible—and politically charged—trade tools.

- Modern economies use tariffs more selectively, but they can have wide-reaching effects.

How It Works

- Ad valorem tariffs: a percentage of the good’s value (e.g. 10%).

- Specific tariffs: a set amount per unit (e.g. $5 per ton).

- Paid by importers: Importers pay the tariff when goods cross the border. These costs are usually passed to businesses or consumers.

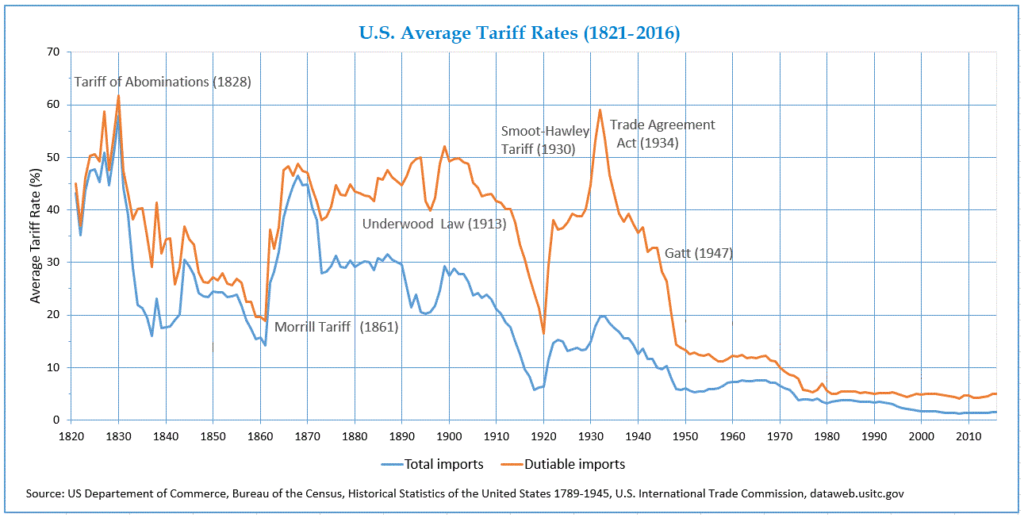

Brief History

- Tariff Act of 1789: One of the first U.S. laws, aimed at revenue and protecting American industry.

- 19th century: Tariffs were the main source of federal revenue. Average duties could exceed 20%.

- Post-Civil War: High protective tariffs prevailed, especially under Republican administrations.

- Smoot-Hawley Act (1930): Raised tariffs sharply; widely blamed for worsening the Great Depression.

- Trade Agreements Act (1934): Started a shift toward reciprocal trade liberalization and lower tariffs.

- Post-WWII–Present: Through GATT and WTO, U.S. tariffs fell significantly, though selective tariffs still occur (e.g. steel, solar panels).

Limitations and Risks

- Higher prices: Tariffs increase the cost of goods for consumers and manufacturers using imported inputs.

- Retaliation: Trade partners may respond with their own tariffs, hurting exporters.

- Revenue role: Tariffs now contribute only a small share of federal revenue, compared to the past.

- Political capture: Protected industries may push for tariffs that benefit them at broader economic expense.

FAQ

- Q: Who pays a tariff?

A: Importers pay the tariff, but the cost is often passed along to consumers. - Q: Are tariffs still important?

A: While less central than in earlier centuries, tariffs remain a powerful—and controversial—policy tool. - Q: Do tariffs work?

A: It depends—some may help targeted industries short term, but they often raise broader costs or invite retaliation.

Sources

- Oxford Economics – “Tariffs 101: What are they and how do they work?“

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary – Definition of “Tariff”