The Myth of Trickle-Down Economics: Why the Next Dollar Doesn’t Reach the Middle Class

The argument shows up the way it always does. Not in a journal. Not on a chalkboard. But in a breakroom. At the dinner table. Visiting your parents (yikes).

Someone brings up taxes. Someone else says the same familiar line: Cut taxes for the people at the top, and the benefits will spread. They invest. They hire. Everybody wins. This is Trickle-down Economics in a nutshell.

It sounds intuitive, like pouring water at the top of a hill and trusting gravity to do the rest.

But in the real economy, the hill is full of traps: savings accounts, debt paydowns, asset markets, and corporate balance sheets that can absorb a dollar without turning it into a paycheck for anyone else. Whether money “trickles down” is not a law of physics. It is a question of behavior.

And that is where a wonky phrase ends up doing more explanatory work than a thousand campaign speeches.

Marginal propensity to consume.

It is the difference between “this tax cut might boost growth eventually” and “this tax cut will show up at the grocery store next week.”

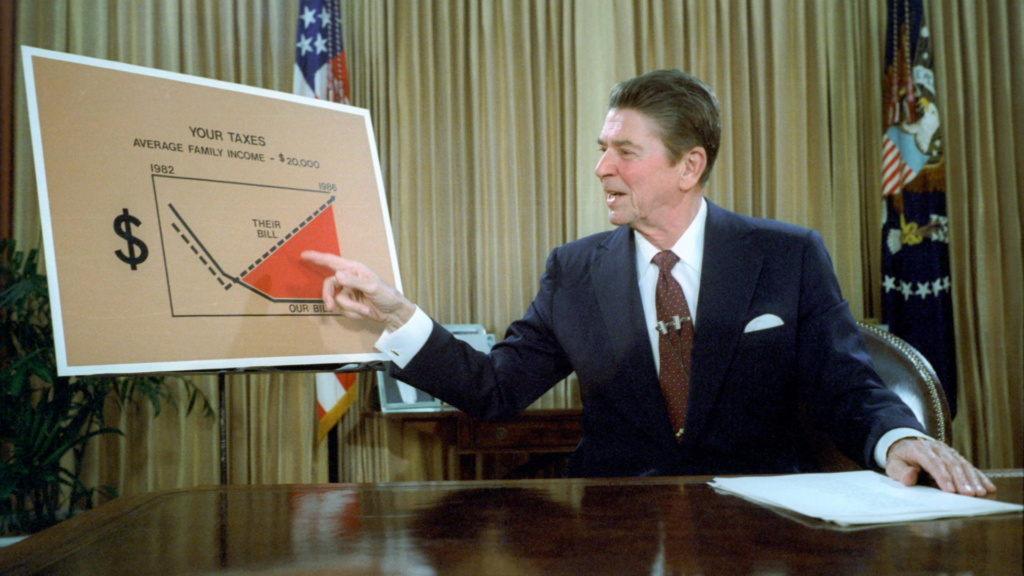

What people mean when they say “Trickle-down” Economics

Economists rarely use “trickle-down” as a precise technical term. It is mostly a political label, often used critically, for policies that tilt benefits toward high-income households and corporations with the claim that growth will spread outward through investment, job creation, and higher wages.

Sometimes that claim overlaps with supply-side ideas: lower marginal tax rates could increase incentives to work, save, invest, start businesses, and expand productive capacity. Sometimes it overlaps with a simpler story: rich people spend money too, so giving them more money must help everyone.

The problem is that these are different mechanisms, operating on different timelines, under different economic conditions.

If you want to know whether a policy is likely to lift broad demand soon, you need to ask a simpler question:

Who gets the next dollar, and what do they do with it?

The “next dollar” question: marginal propensity to consume

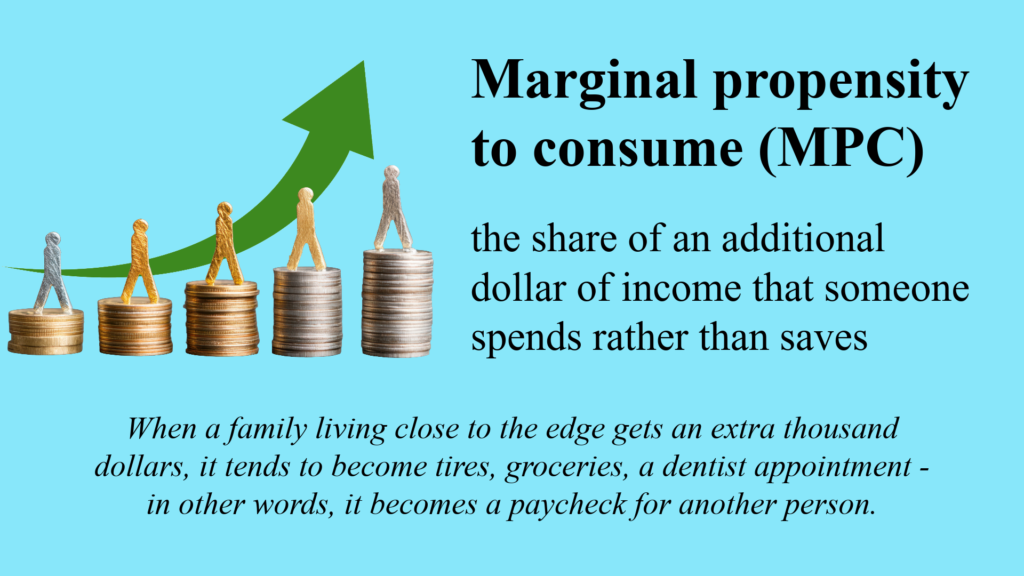

Marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is the share of an additional dollar of income that someone spends rather than saves. If your MPC is 0.8, you spend 80 cents of each extra dollar and save 20.

That sounds abstract until you put it in a scene.

Two households, two tax cuts

- Household A gets a $1,000 tax cut.

- They are behind on bills, their car needs work, and they have been delaying a dentist appointment.

- They spend most of it quickly.

- Household B gets a $1,000 tax cut.

- They are financially comfortable.

- They pay down a chunk of a credit line, add to savings, or buy a financial asset.

Both “used” the money. But only one version reliably turns into immediate purchases of goods and services.

A large body of research finds MPC tends to be lower among higher-wealth households, meaning a dollar shifted toward the top is less likely to translate into near-term consumer demand.

This is about incentives, not virtue. It is math and circumstance. If your essentials are already covered, the next dollar is easier to park than to spend.

Why MPC turns into real-world power: the multiplier

When someone spends that extra dollar, it becomes someone else’s income. That second person spends a portion of it, too. That chain is the basic intuition behind the Keynesian multiplier, and why MPC matters so much when policymakers are trying to boost demand.

The Keynesian multiplier is a macroeconomic theory stating that an initial increase in government spending results in a larger increase in national income and GDP. It posits that one person’s spending becomes another’s income, generating a chain reaction of consumption.

But the multiplier is not magic. The chain weakens when dollars leak into:

- Savings and debt repayment

- Imports

- Higher prices instead of higher output

- Financial assets that do not immediately fund new production

So the policy question becomes: Are we trying to increase demand soon, or expand supply over time?

Those are not the same project.

The part trickle-down gets right

Here is the steelman case for the “top-down” approach.

High-income households and corporations do more saving and investing. If tax cuts increase after-tax returns, you could see:

- More capital formation

- More business investment

- More innovation

- Higher productivity

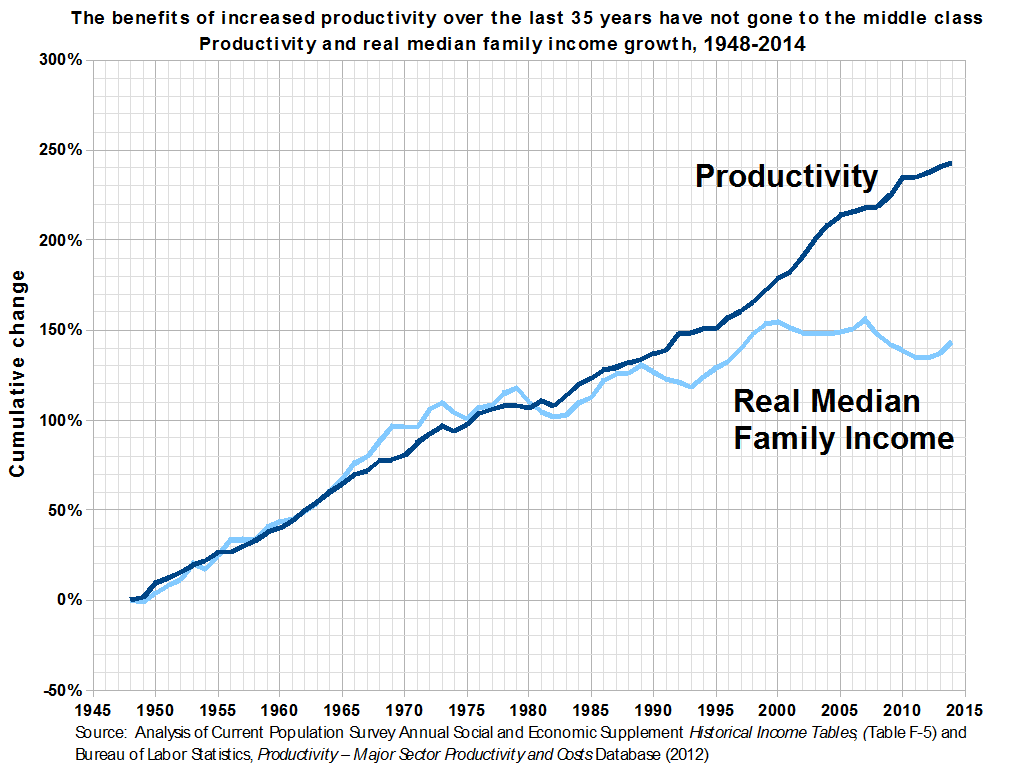

Over time, higher productivity can support higher wages and lower prices, even for people who never got the tax cut.

That is the argument. And it is not nonsense.

The real dispute is about how reliably it happens, how long it takes, and who captures the gains in the meantime.

In plain English: investment-led growth is real, but it is not automatic, and it can coexist with wages that lag behind profits for a long time.

The part “trickle-down” economics often gets wrong

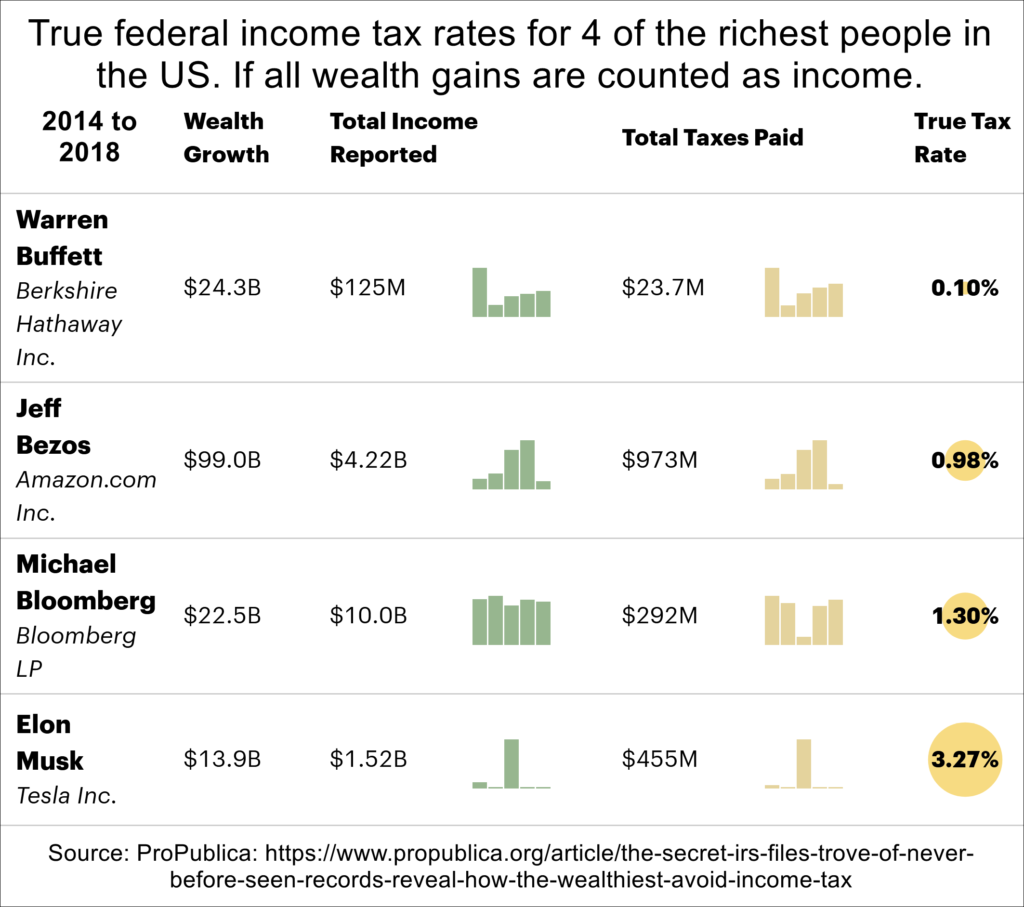

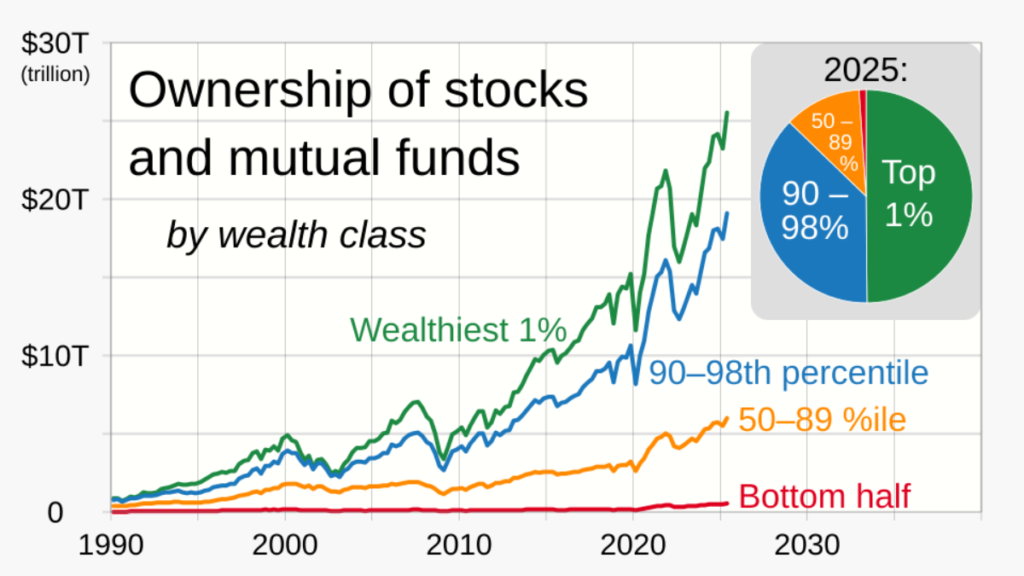

1) It assumes money becomes investment, not just wealth

A tax cut for a high-income household can become:

- A new factory, or

- A larger portfolio

Both are “investment” in casual conversation. Only one expands productive capacity in the near term.

In a modern financial system, it is easy for extra money to flow into asset prices, especially when businesses do not see enough customer demand to justify expansion.

If demand is weak, companies can respond to tax cuts by:

- Buying back stock

- Paying dividends

- Paying down debt

- Sitting on cash

None of those are inherently bad. But they are not the same as broad-based job growth.

2) It treats “the rich” as a single behavior type

Even among wealthy households, MPC is not uniform. Some households appear “wealthy” on paper but are cash-constrained, a condition researchers call “wealthy hand-to-mouth.” They may hold illiquid assets but still spend a large share of extra cash.

So the real world is messy. Still, the broad empirical pattern remains: Marginal propensity to consume (MPC) tends to fall as wealth rises.

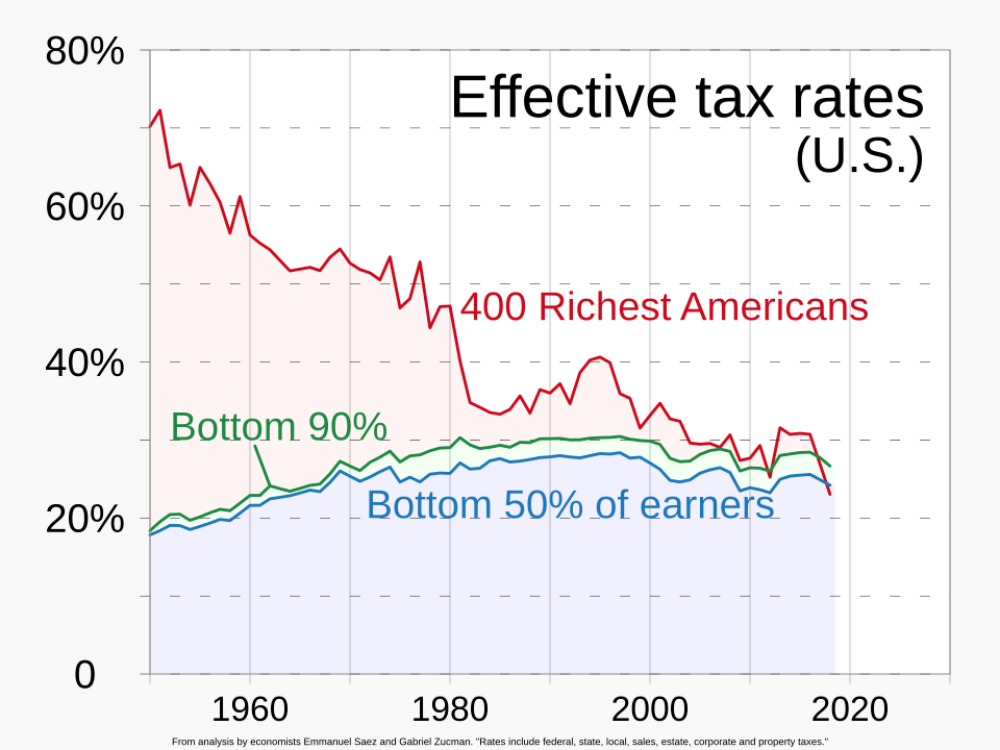

3) It oversells the growth record of tax cuts for the rich

If “trickle-down” were a consistent growth machine, you would expect a simple pattern: major tax cuts on top incomes would predictably produce stronger broad economic performance.

Cross-country evidence has found that major tax cuts for the rich are associated with higher income inequality, while not showing clear, statistically significant improvements in growth and employment on average.

US-focused research also finds that tax cuts targeted to lower-income groups tend to have stronger effects on employment and growth than tax cuts aimed at higher-income groups.

This is the empirical spine of the critique: if your goal is broad demand and jobs, who gets the dollar matters.

Why “trickle-down” economics keeps winning arguments anyway

Because it offers a comforting shortcut.

It tells people you can have:

- lower taxes for those with the most political power,

- higher growth,

- and rising living standards for everyone,

without naming tradeoffs.

And in some conditions, it can feel true. If the economy is already booming, if credit is flowing, if technology is exploding, many boats rise. But that does not prove the policy caused the tide.

It is easy to mistake a rising market for a rising economy.

What the MPC lens changes about policy debates

Once you take MPC seriously, a lot of political fights look different.

Tax cuts vs. transfers

If you want near-term demand, dollars directed to households with higher MPC tend to move faster into consumption.

Inequality and growth

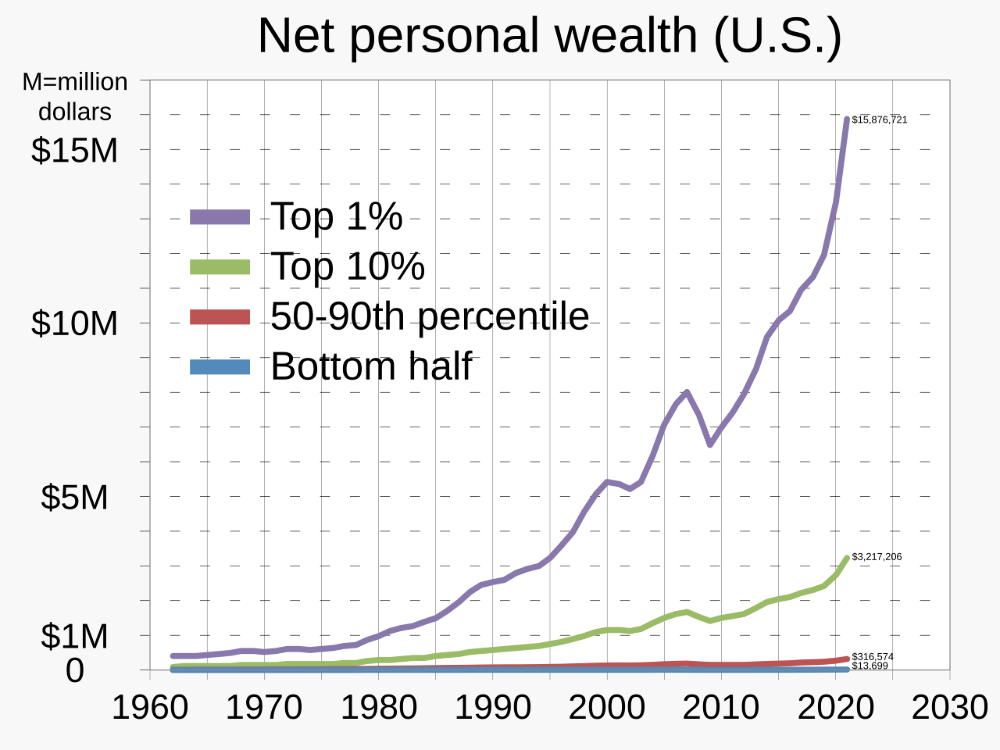

When more income flows to the top and less to the bottom, aggregate demand can weaken if the top saves more of the marginal dollar. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has argued that excessive inequality can undermine the durability of growth, in part because higher-income households spend a smaller share of their income.

Timing matters

If your goal is long-term productivity, policy that boosts investment, education, infrastructure, R&D, and competition can matter more than simple rate cuts.

MPC does not say “never cut taxes at the top.” It says: do not pretend all dollars are equal in their short-run economic impact.

The honest version of the story

The most accurate takeaway is also the least slogan-friendly.

- Short run: Money directed toward households with a higher MPC is more likely to raise demand quickly.

- Long run: Investment and productivity growth drive living standards, but the path from “tax cut” to “new factory” is not automatic.

- Distribution: Even when the economy grows, who captures the gains depends on institutions and bargaining power, like labor markets, union strength, corporate governance, and competition policy.

- Context: The state of the economy matters. A demand boost during high unemployment can produce more output. The same boost in a supply-constrained economy can show up as higher prices.

This is why “trickle-down” is best understood as a myth in the rhetorical sense: a simple story that flattens a complex system into one neat promise.

The economy does not trickle. It routes.

Bottom line

Trickle-down economics sells the idea that benefits delivered to the top will reliably spread to everyone else.

Marginal propensity to consume explains why that often fails in the short run: higher-wealth households tend to spend less of the next dollar, so top-heavy tax cuts can produce a weaker immediate demand boost than policies aimed at households more likely to spend.

Meanwhile, the strongest evidence base suggests that tax cuts for the rich tend to raise inequality and do not consistently deliver broad growth and employment gains on average.

If you want to argue about economic policy honestly, start here:

Stop asking whether money will “trickle down.” Ask where the next dollar goes, and how quickly it returns to the real economy.

Quick definitions

- Trickle-down economics: A political label, usually critical, for policies that disproportionately benefit higher-income households or corporations on the theory that gains will spread through investment and growth.

- Marginal propensity to consume (MPC): The share of an additional dollar of income that is spent rather than saved.

- Multiplier: The idea that one person’s spending becomes another person’s income, creating rounds of additional spending, with strength shaped by MPC and economic conditions.