How Labor Unions Changed Work in America

From 19th-century fights for the eight-hour day to today’s Hollywood and auto strikes, learn how unions emerged, what they won for workers, how laws and industry reshaped them, and why they’re once again at the center of debates over wages, safety, and inequality.

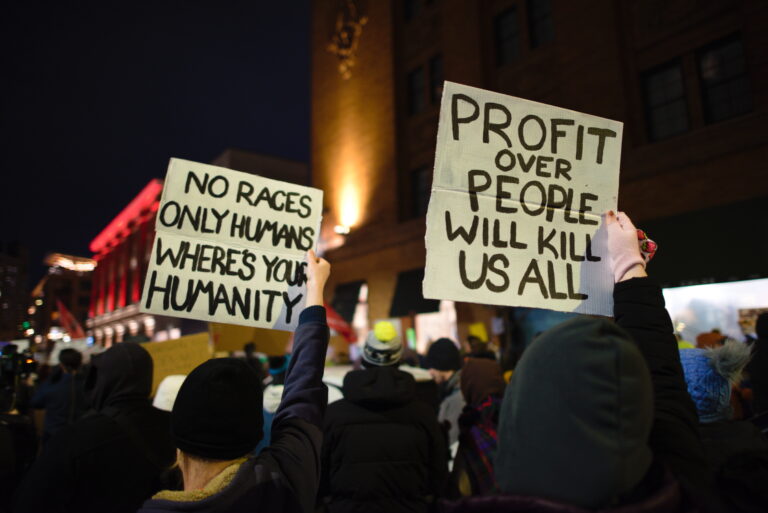

On a gray morning in the fall of 2023, actors in Los Angeles, auto workers in Michigan, and health-care staff in California all did the same quiet, radical thing: they stopped working. Their strikes helped make 2023 one of the most strike-heavy years in recent decades, with nearly 459,000 workers involved in major work stoppages—an increase of more than 280% over the year before.

To some people, these scenes look like a comeback story for organized labor. To others, they’re a reminder of the disruption unions can bring. To understand what unions are doing today, and whether they’re helpful or harmful to workers and the wider economy, you have to go back more than two centuries—because the story of unions is basically the story of how American work changed.

What is a labor union, in plain language?

At its core, a labor union is simple: it’s an organization of workers who band together to bargain as a group for better pay, safer conditions, and fairer treatment. Instead of each worker negotiating alone, they negotiate collectively. If negotiations fail, they may use their biggest source of leverage—refusing to work, via strikes or other collective actions.

Unions are funded by dues paid by members and governed by elected leaders. They negotiate binding contracts that typically cover wages, hours, benefits, and grievance procedures. The details change over time, but the basic idea has stayed remarkably consistent: workers pooling power to balance the power of employers.

Early roots: from colonial craft workers to the first unions

The first stirrings of organized labor in what would become the United States began long before factories and assembly lines.

- In 1768, journeymen tailors in New York City went on strike to protest wage cuts—often cited as the first recorded strike in what would become the United States.

- In 1794, shoemakers in Philadelphia formed the Federal Society of Journeymen Cordwainers, one of the first sustained trade unions in the country.

These early groups were small, local associations of skilled craftsmen—carpenters, printers, cordwainers—who published price lists for their work and pushed back against wage cuts and longer hours.

Their power, however, was fragile. In 1806, employers sued the Cordwainers for “criminal conspiracy,” arguing that workers banding together to demand higher wages was illegal. A court agreed, essentially criminalizing union activity for decades.

Only in 1842, through the Massachusetts case Commonwealth v. Hunt, did courts begin to recognize that unions, in themselves, were not criminal conspiracies. That ruling opened the door for more sustained organizing.

Meanwhile, the economy was changing. The Industrial Revolution brought factories, long hours, and dangerous conditions, especially in urban centers. Workers began to see that individual complaints weren’t enough. If employers could coordinate, workers would have to as well.

The 19th century: long hours, dangerous work, and the fight for the 8-hour day

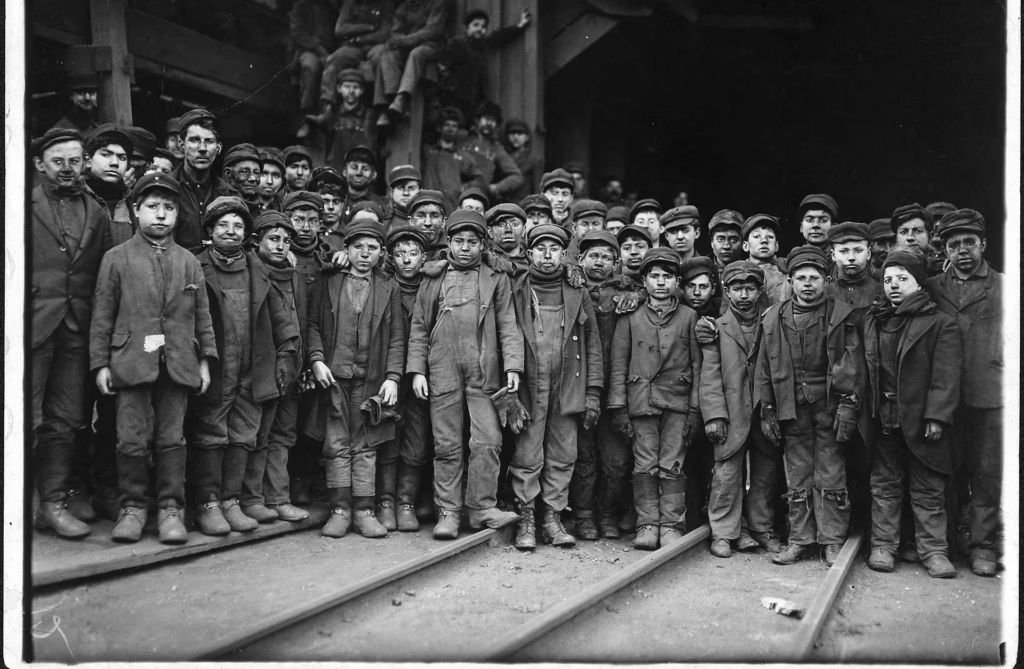

By the mid-1800s, the United States was transforming into an industrial powerhouse. That transformation came with harsh realities: 10- to 12-hour days, six-day weeks, widespread child labor, and few safety rules.

New organizations sprang up to meet this moment:

- National Labor Union (NLU) (founded 1866) — the first national federation of unions, which pushed hard for an eight-hour workday and better conditions for industrial workers.

- Knights of Labor (rose in the 1870s–1880s) — a broad movement that tried to organize both skilled and unskilled workers, including some women and Black workers, and that advocated for a “cooperative commonwealth” rather than just higher wages.

The 8-hour day became a rallying cry. In 1872, a massive Eight-Hour Day strike in New York City involved roughly 100,000 workers. Throughout the late 19th century, workers repeatedly walked off the job to demand shorter hours, better pay, and the basic idea that they should have lives outside of work.

But employers—and often the government—pushed back hard.

When the government took the company’s side

Two notorious conflicts show how violently labor disputes could be suppressed:

- Pullman Strike (1894): About 250,000 railroad workers joined a strike over wage cuts and high company-town rents at the Pullman Company. President Grover Cleveland sent federal troops to break the strike; clashes killed dozens of people. Union leaders were jailed, and the American Railway Union was effectively crushed.

- Colorado Coalfield War and Ludlow Massacre (1913–1914): Coal miners striking over brutal conditions were evicted from company housing and lived in tent colonies. In April 1914, the Colorado National Guard and company guards attacked a tent camp at Ludlow, killing at least 21 people, including children. Violence continued for months; despite the bloodshed, the strike ended without substantial concessions.

Unions were gaining members and visibility, but they were also learning a hard lesson: without legal protection, organizing often meant risking your job, your home, and sometimes your life.

Tragedy and reform: the push for safety and child-labor laws

The early 1900s were filled with images that are now iconic: young “breaker boys” in coal mines, children working 12-hour days in canneries and textile mills, families stitching lace or peeling shrimp late into the night just to survive.

One disaster became a turning point:

- Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire (1911): Locked doors and unsafe conditions in a New York garment factory turned a fire into a catastrophe, killing 146 workers—most of them young immigrant women. The outrage that followed helped galvanize unions and reformers to demand safety regulations, fire codes, and factory inspections.

Unions made workplace safety a central demand, especially in dangerous industries like mining, steel, and manufacturing. Over time, their efforts contributed to:

- Workers’ compensation laws for on-the-job injuries

- Early safety rules and inspections

- A growing understanding that government had a role in setting minimum standards for work

These efforts laid the groundwork for later landmark laws, including the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) in 1970, which empowered the federal government to enforce health and safety standards at work.

World War I and the turbulent 1919 strike wave

During World War I, organized labor gained strength and some recognition from the government, particularly where war production was concerned. But the end of the war unleashed pent-up frustration. Inflation had eroded wages—food prices more than doubled between 1915 and 1920, and clothing costs more than tripled.

In 1919, more than 4 million workers—about a fifth of the U.S. workforce—went on strike. This wave included:

- A general strike in Seattle

- A major steel strike involving around 365,000 workers

- Hundreds of thousands of coal miners walking out

Business leaders and many politicians framed these strikes as radical threats—partly because they happened amid fears of Bolshevism after the Russian Revolution. The result was a backlash: many gains from the war years were rolled back, union membership fell from 5 million to 3 million, and courts struck down child-labor and minimum-wage laws.

It was a preview of a pattern that would recur: periods of union growth followed by intense resistance.

The New Deal era: unions’ “golden age”

The Great Depression and the New Deal fundamentally reshaped the rules of the game.

Facing mass unemployment and economic collapse, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration embraced policies that, for the first time, explicitly protected workers’ right to organize:

- National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) of 1935 – guaranteed private-sector workers the right to form unions, bargain collectively, and strike, and created the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to enforce those rights.

- Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938 – established a federal minimum wage, overtime pay for hours beyond 40 per week, and new restrictions on child labor.

These laws didn’t hand everything to unions, but they shifted the playing field. Combined with militant organizing tactics—like the Flint sit-down strike of 1936–37, where autoworkers literally occupied General Motors factories—unions began winning recognition and contracts in mass-production industries.

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) (later merged with the American Federation of Labor to form the AFL–CIO) led drives to organize entire industries: auto, steel, rubber, and more.

After World War II, unions reached peak strength:

- By the 1950s, more than one-third of the U.S. workforce belonged to a union.

- Union pay and benefits helped create a broad middle class, turning once-low-paid industrial jobs into stable careers with health insurance, pensions, and paid leave.

This was the era when the classic image of the “union job”—good wages, strong benefits, and job security—became real for millions of families.

Rules, rights, and limits: how labor law works

Today’s union landscape rests on a cluster of key laws and institutions:

- National Labor Relations Act (NLRA): Governs most private-sector union organizing and collective bargaining. It bans employers from firing or retaliating against workers for union activity and requires bargaining in good faith.

- National Labor Relations Board (NLRB): Enforces the NLRA, runs union elections, and investigates unfair labor practices.

- Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA): Sets federal rules on minimum wage, overtime, and child labor.

- Taft-Hartley Act (1947): Amended the NLRA, banning some union tactics, allowing states to pass “right-to-work” laws, and placing limits on political activities by unions.

Cornell University]

The right to strike (and its limits)

Under federal law, workers cannot be fired for participating in a protected strike or picketing—though there are important caveats.

- Protected strikes include most strikes over wages, hours, or working conditions, or to protest unfair labor practices.

- Unprotected strikes—for example, certain intermittent strikes, purely political strikes, or strikes that involve serious misconduct or violence—can lead to lawful termination.

- After a strike ends, workers usually have a right to reinstatement, though in “economic strikes” employers can sometimes hire permanent replacements, with returning strikers placed on a preferential recall list.

Public-sector workers are governed by a different patchwork of federal and state laws. Federal employees in many roles—famously, air traffic controllers—are barred from striking. In 1981, when the air traffic controllers’ union (PATCO) went on strike, President Ronald Reagan fired more than 11,000 of them and decertified the union, signaling a tougher era for organized labor.

Decline: deindustrialization, politics, and the shift to service work

If the mid-20th century was unions’ high point, the late 20th century was a long slide.

Several forces converged:

- Deindustrialization and globalization: Many heavily unionized manufacturing jobs moved abroad or disappeared, replaced by service-sector work that was harder to organize.

- Employer resistance: Companies increasingly hired anti-union consultants, used legal delays, and closed unionized plants or reopened them nonunion.

- Legal and political changes: Court decisions and policies narrowed the scope of protected activity in some cases, and more states adopted “right-to-work” laws that undermine union finances by allowing workers covered by union contracts to opt out of paying dues.

By 2022, union membership had fallen to about 14.3 million workers, or 10.1% of the workforce. Only 6.0% of private-sector workers were unionized, compared with 33.1% of public-sector workers.

Some see this decline as a necessary adjustment in a global, competitive economy. Others see it as the erosion of a key pillar of the middle class.

What unions changed: wages, benefits, safety, and inequality

Regardless of where you stand politically, there are some concrete, measurable ways unions have reshaped work in the United States.

1. Wages and benefits

Research from the Economic Policy Institute and others finds that, on average:

- Workers covered by a union contract earn about 13% more in wages than comparable nonunion workers in the same sector.

- Union workers are far more likely to have employer-provided health insurance, pensions, paid sick days, and paid vacation than similar nonunion workers.

Unions don’t just set wage floors; they also negotiate detailed benefit packages and due-process protections. Many union contracts require employers to show “just cause” and follow clear procedures before firing workers, which is much more protective than typical at-will employment.

2. Safety

Safety has always been a central union concern. From coal miners demanding better ventilation and equipment to factory workers pressing for machine guards and fire exits, unions have pushed for:

- Accident reporting and investigations

- Safety committees and training

- Stronger enforcement of regulations, leading up to the creation of OSHA in 1970

A historical review from OSHA-focused educators notes that union pressure helped drive the adoption of workers’ compensation laws, safety inspections, and, ultimately, the OSHA framework that applies today.

3. Equality

Unions have a complicated history on race and gender—many early unions explicitly excluded Black workers, women, and immigrants. Over time, new organizations like the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), leaders like A. Philip Randolph (Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters), and women organizing during World War II pushed unions to become more inclusive.

Modern data show that:

- Black and Hispanic workers receive larger wage boosts from unionization than white workers.

- Women represented by unions earn about 9% higher hourly wages than comparable nonunion women.

Unions also reduce overall wage inequality. One estimate suggests that the decline of unions explains about one-third of the rise in wage inequality among men and one-fifth among women between 1973 and 2007, as middle-wage workers lost the bargaining power unions once provided.

In short: unions tend to compress wage distributions, pulling up the bottom and middle more than the top.

Strikes then and now: from the Great Railroad Strike to Hollywood and health care

Throughout U.S. history, major strikes have marked turning points—not just for specific workers, but for public attitudes and policy.

Historical highlights include:

- Great Railroad Strike of 1877: A wave of walkouts against wage cuts paralyzed rail traffic nationwide and was met with troops and violence.

- Homestead Strike (1892): A bloody clash between steelworkers and Pinkerton guards at Andrew Carnegie’s Homestead plant in Pennsylvania.

- Lawrence “Bread and Roses” strike (1912): Immigrant textile workers in Massachusetts protested wage cuts, coining the slogan that workers deserve bread (decent pay) and roses (quality of life).

- Memphis sanitation workers’ strike (1968): Black sanitation workers demanding dignity and safety marched under signs reading “I AM A MAN”; Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated while supporting them.

A long list of major U.S. strikes by size shows that large-scale work stoppages have never entirely disappeared, from coal strikes in the early 1900s to teachers’ strikes and communication workers’ strikes in recent decades.

The new wave: 2018–2023

After a relatively quiet period, the 2010s and early 2020s saw a resurgence of large-scale labor actions:

- Teachers’ strikes (2018–2019) in multiple states highlighted low pay, large class sizes, and underfunded schools.

- In 2023, according to Economic Policy Institute analysis, 458,900 workers took part in major work stoppages—strikes or lockouts involving at least 1,000 workers—up more than 280% from 2022 levels.

Examples from 2023 include:

- SAG-AFTRA actors’ strike: About 160,000 actors walked out, making it one of the largest disputes in decades, demanding better pay and protections against AI and streaming-era changes.

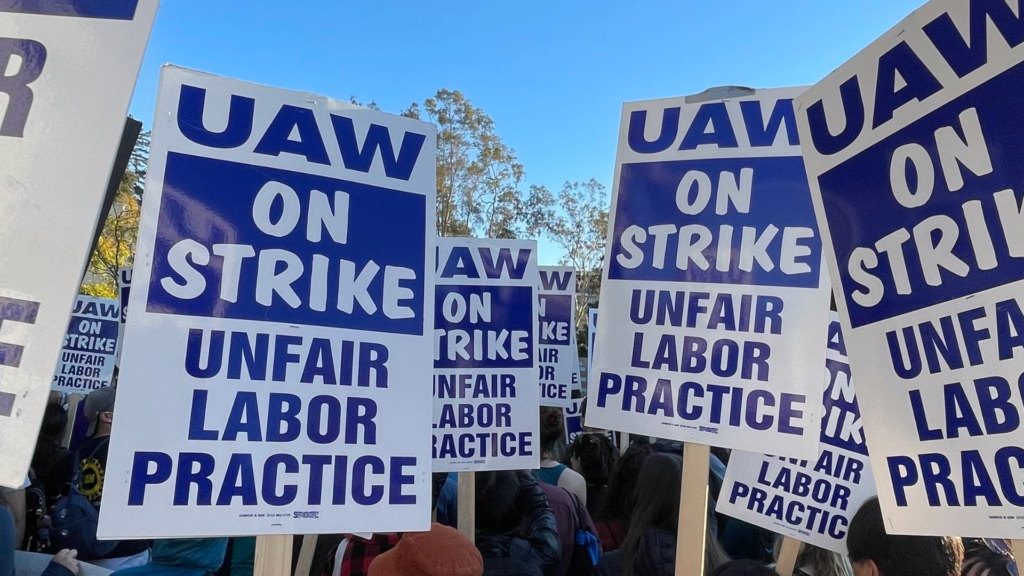

- United Auto Workers “Stand Up” strike: Roughly 53,000 workers at Ford, GM, and Stellantis used a rolling strike strategy and ultimately won raises of 30-plus percent, elimination of a two-tier wage system, and commitments linked to the electric-vehicle transition.

- Kaiser Permanente health-care strike: Over 75,000 workers participated in the largest health-care strike in U.S. history, winning substantial raises, staffing commitments, and new minimum wages in their contract.

These high-profile conflicts were part of a broader pattern: workers in health care, higher education, retail, museums, and even tech and logistics are experimenting with organizing and strikes as leverage in an economy marked by inflation, high corporate profits, and long-running wage stagnation.

The state of unions today: low membership, high public interest

Formally, union membership is far below mid-century peaks. As of 2024, only about one in ten American workers is in a union, and most of those are in the public sector.

Yet public opinion has shifted in a different direction:

- A 2022 Gallup poll found 71% of Americans viewed unions favorably, the highest level of support since the mid-1960s.

At the same time, workers are filing more petitions for union elections and launching organizing drives at big-name employers in coffee shops, warehouses, media, and higher education. Union-contract coverage increased slightly in 2023, with more than 16.2 million workers represented by unions, even though overall unionization rates remained low.

New issues on the table

Modern unions are not just negotiating over hourly pay. Common themes now include:

- Protection against erratic scheduling and forced overtime

- Mental-health support and manageable workloads, especially in health care and education

- The use of AI and automation in creative and tech fields

- Job security and fair treatment for gig workers and contractors

- Diversity, equity, and inclusion within workplaces and within unions themselves

The core mission is familiar—workers seeking a voice and fair share—but the context is very 21st-century.

Challenges unions face

Despite renewed energy, union organizers and members face structural obstacles:

- Legal gaps and weak enforcement

- Penalties for illegal retaliation (like firing union supporters) are often modest, and cases can drag on for years.

- Many workers—such as independent contractors, agricultural workers, and domestic workers—are partially or fully excluded from NLRA protections.

- “Right-to-work” and financial strain

- In right-to-work states, unions must represent all workers in a bargaining unit but cannot require them to pay dues, which can strain resources and reduce bargaining power.

- Fragmented workplaces

- Modern employers often rely on subcontracting, temp agencies, and franchise models, making it harder for one union to bargain with the entity that actually controls wages and conditions.

- Public perception and internal issues

- Historical exclusion of women and people of color, corruption scandals in some unions, and political divisions can all undermine trust.

- Some workers worry about dues, fears of reprisals, or whether a union can deliver concrete improvements.

- Economic and technological change

- Automation, global supply chains, and platform-based work (apps, gig platforms) constantly reshape jobs faster than law and union structures can adapt.

Unions are experimenting with new forms—sectoral bargaining, worker centers, and multi-employer campaigns—but the rules of the game still make organizing a steep uphill climb in many industries.

So… are unions helpful for workers and the economy?

That’s the question at the heart of almost every debate about unions. Looking at the evidence and history, a few things stand out.

The case that unions help workers and the broader economy

Research and historical experience suggest unions:

- Raise wages and benefits not just for their members, but often for nearby nonunion workers too, as employers increase pay to compete.

- Reduce wage inequality, especially between middle- and high-wage workers, and help close racial and gender wage gaps.

- Improve safety and working conditions, lowering injury rates and giving workers a structured way to address hazards.

- Stabilize the middle class, by turning low-wage or volatile jobs into more predictable careers with benefits.

From the eight-hour day and the weekend to child-labor bans and OSHA, many protections people take for granted today were hard-fought demands of union campaigns.

The case that unions can create costs or distortions

Critics argue that unions can:

- Increase labor costs, which may lead to higher prices or push some businesses to mechanize or relocate.

- Make it harder to adapt quickly in industries facing rapid technological or competitive change.

- Cause disruptions through strikes or work stoppages, especially in vital services like transportation or health care.

- Occasionally protect poor performers or resist necessary changes in work organization.

Historically, some unions not only excluded certain workers but also aligned with discriminatory or nativist policies—a real harm that took decades of internal reform to confront.

The bottom line

Whether unions are “good” or “bad” depends a lot on what you value and which outcomes you prioritize. But several conclusions are hard to escape:

- For individual workers, particularly in low- and middle-wage jobs, unions have consistently delivered higher pay, better benefits, and greater voice at work.

- For society, unions have played a central role in building workplace standards—like minimum wage, overtime, safety rules, and child-labor bans—that now apply even in places without unions.

- For the economy, unions tend to reduce extreme inequality and support a broad middle class, though they can also introduce rigidities and sometimes conflict in the short term.

Standing on a picket line today is not the same as striking in 1894 or 1937. But the core questions haven’t really changed:

Who gets to decide what work is worth? Who bears the risk when markets change? And how much say should workers have in the places where they spend so much of their lives?

Labor unions are one answer Americans have been testing, revising, and fighting over for more than two centuries. Whatever comes next—whether unions continue to rebound, reinvent themselves, or recede—the story of work in the United States can’t really be told without them.