Socialism: What It Is, Where It Came From, and Why People Still Argue About It

It’s one of America’s most loaded words—tangled in history, fear, and hope. But what does “socialism” actually mean today, and why does the definition matter more than the label?

Check out our concise explainer here.

“Socialism” is one of those words that can mean very different things depending on who’s saying it. In academic writing, it typically refers to economic systems where major resources and productive enterprises are socially owned or controlled—through the state, through local communities, through worker cooperatives, or some combination—often with the goal of aligning the economy more closely with equality, democratic accountability, and meeting human needs.

In everyday politics, though, “socialism” is often used as a label—sometimes proudly, sometimes as an accusation—covering everything from universal healthcare to full public ownership of industries. That gap between the technical definition and the popular use is a big reason debates about socialism can feel like people are talking past each other.

The core idea: “social” control of the economy

Most definitions of socialism share a family resemblance:

- Ownership/control: Instead of private owners controlling most large-scale production, society collectively controls key productive assets (the “means of production”)

- Purpose: Production is oriented less around private profit and more around broad social goals—like reducing poverty, ensuring basic needs, and limiting extreme inequality.

- Coordination: Some socialist models emphasize economic planning; others keep markets but change who owns firms and how power is distributed.

That last point matters: socialism is not one single blueprint. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy calls it a “rich tradition” with many competing schools and definitions.

Socialism vs. social democracy vs. democratic socialism

A lot of confusion comes from the fact that modern countries are usually mixed economies: they blend private business, government regulation, public services, and social insurance. The labels people use for those mixes differ.

Social democracy

Historically, social democracy began as a movement aiming (in theory) for a gradual transition from capitalism to socialism. Over time—especially in the second half of the 20th century—it often came to mean a more moderate approach: regulated capitalism plus a strong welfare state, not necessarily public ownership of most industry.

Democratic socialism

Democratic socialists generally argue for moving beyond capitalism (not merely regulating it) while insisting that socialism should be achieved and maintained through democratic, pluralist politics, not one-party rule. Definitions vary, but Britannica notes that democratic socialism is distinguished from social democracy by its anti-capitalist aim (even if strategies differ).

In practice: Many people use these terms interchangeably, especially in U.S. politics, where “socialism” can function as shorthand for “big government” or “European-style welfare policies.” But in political theory, the distinctions matter.

Origins: from early reformers to Marx

Socialist ideas emerged in Europe during the upheavals of industrialization, when factory labor, urban poverty, and extreme wealth inequality became harder to ignore. Early socialist thinkers and movements often focused on:

- Exploitation and power: Who benefits from industrial production—and who gets stuck with low wages and dangerous work.

- Community and solidarity: The belief that society is interdependent and that economic life should reflect cooperation rather than pure competition.

Karl Marx (and many after him) argued that capitalism contained internal conflicts that would drive social change; other socialists pursued cooperative experiments, trade union politics, or parliamentary reforms. The tradition quickly split into multiple branches—revolutionary, reformist, anarchist, and later, democratic socialist and social democratic currents.

Different “models”

Because socialism is a tradition, not a single policy package, it helps to think in families of models:

1) State socialism (public ownership through government)

This model emphasizes nationalization of major industries and centralized coordination. It’s the kind of arrangement many people picture first, especially because of 20th-century examples. Critics often worry about bureaucracy, inefficiency, and—most importantly—political concentration of power.

2) Democratic/participatory socialism (power dispersed, politics pluralist)

Here, the emphasis is on ensuring that economic power is democratically accountable—through elections, strong unions, public oversight, and institutional checks—rather than concentrated in private owners or a single ruling party.

3) Market socialism (markets stay, ownership changes)

Market socialism keeps buying and selling in markets (prices still exist), but enterprises may be publicly owned, municipally owned, or worker-owned/cooperative. Think of it as trying to combine market coordination with a more egalitarian ownership structure.

4) Cooperative socialism (worker ownership and workplace democracy)

Some visions of socialism center on the workplace: firms are run as cooperatives, where workers share control and profits, aiming to reduce hierarchical employer–employee power dynamics.

Real-world systems can blend these approaches—and most countries blend socialist and capitalist elements in some form.

Socialism and communism: related, but not identical

People also commonly mix up socialism and communism. Even among theorists, the boundary can be debated. Britannica notes that Marx sometimes used the terms in overlapping ways, while later traditions treated communism as a more “advanced” stage beyond socialism.

In everyday usage today, a simple way to frame it is:

- Socialism: social ownership/control of major economic resources can exist in multiple political forms (including democratic ones).

- Communism: often refers to a system aiming for a classless society and, in historical cases, became associated with one-party states that claimed to rule in the name of the working class.

That historical association is why many people react to “socialism” with concern about authoritarianism—even when a speaker means a democratic welfare-state model.

The case for socialism: what supporters emphasize

Supporters typically argue that socialism addresses problems they see as baked into capitalism:

- Inequality and insecurity: Markets can generate wealth, but also sharp inequality, volatile employment, and unequal bargaining power between employers and workers.

- Public goods and basic needs: Healthcare, education, housing, and infrastructure may be treated as rights or necessities that shouldn’t depend heavily on the ability to pay.

- Democracy beyond politics: If a small group controls most economic resources, supporters argue, political equality can be undermined by economic power.

Even many non-socialists accept parts of this critique, which is why policies like public education, Social Security-style programs, and certain regulations exist in otherwise capitalist societies.

The case against socialism: what critics emphasize

Critics’ concerns vary depending on which model is being discussed, but common arguments include:

- Incentives and innovation: If profits are limited or ownership is diluted, will people invest, take risks, and innovate at the same pace?

- Efficiency and information: Central planning can struggle to process complex, fast-changing information that decentralized markets capture through prices.

- Bureaucracy and capture: Large public systems can become rigid, politically manipulated, or dominated by insiders.

- Power concentration: The biggest fear is political: if the state controls much of the economy, it may become harder to challenge the state—especially without strong democratic institutions.

Notably, some socialists share the “power concentration” worry—just aimed at private concentrations of wealth—and push models like cooperatives or market socialism to reduce both corporate and state domination.

Why the word still sparks intense debate in the U.S.

In the United States, socialism’s meaning is shaped heavily by Cold War history, modern partisan politics, and the fact that many people use “socialism” to describe policies that political scientists might call social democracy or welfare-state capitalism.

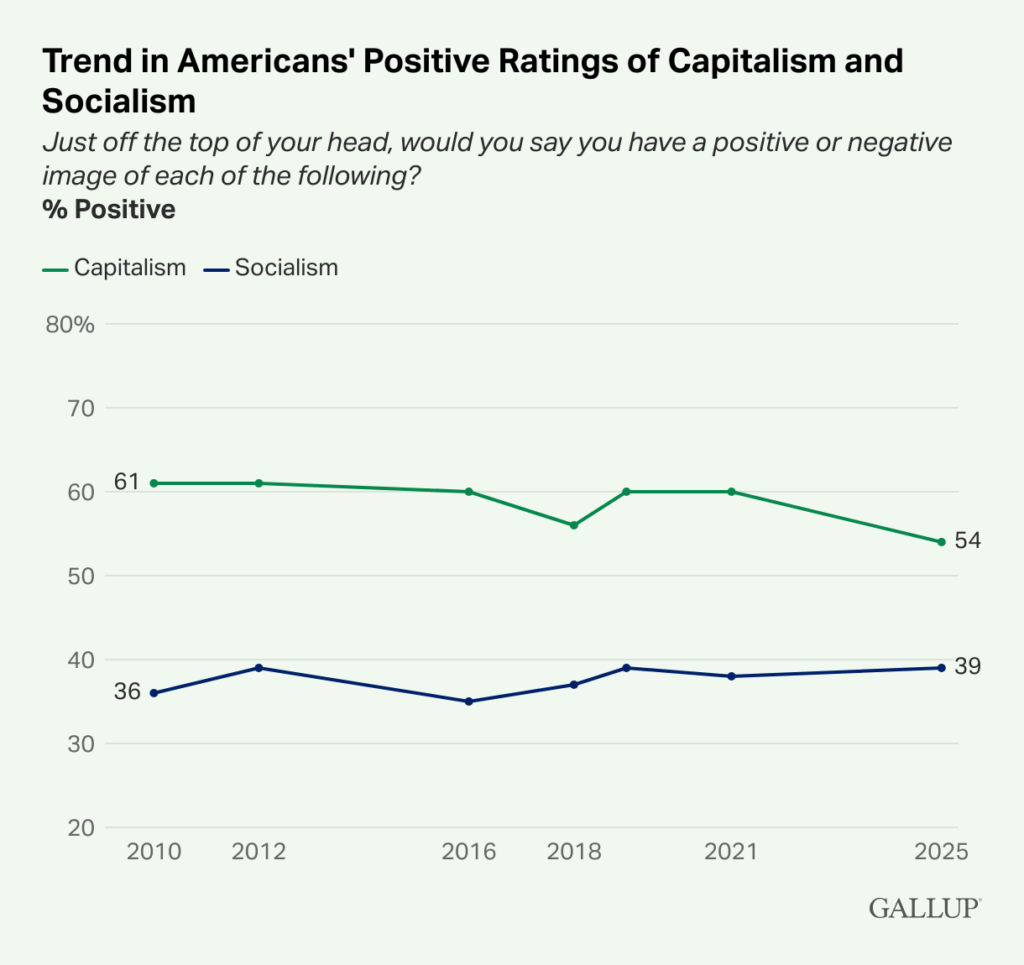

Polling captures this ambivalence. A Gallup report in September 2025 found Americans remained more positive (54% in favor) toward capitalism than socialism overall, while attitudes toward socialism were sharply polarized by party. A Pew Research Center survey has similarly found that Americans often associate capitalism with opportunity and freedom, and socialism with meeting basic needs—again with large partisan differences.

In other words, “socialism” persists not only as a set of theories about ownership and power, but as a live cultural symbol: a stand-in for deeper arguments about fairness, freedom, security, and the role of government.

Bottom line

Socialism isn’t one thing. At its core, it’s a family of ideas and systems built around social control of major economic resources and a belief that the economy should serve broad human needs—not only private profit.

Whether people see socialism as a path to greater freedom and equality or a recipe for inefficiency and dangerous power depends on which version they mean—and on how much trust they place in democratic institutions to keep economic power accountable.