When the Labs Go Dark: What Scientific Research Actually Is — And Why Losing It Matters

In late January 2025, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued an “immediate pause” on many public communications and document releases across its agencies, including the National Institutes of Health (NIH), in effect through at least Feb. 1.

In the days that followed, multiple outlets reported knock-on effects inside NIH that reached far beyond press releases, including disrupted or delayed grant review activity and cancelled meetings, in part because required meeting notices were not being posted as usual.

Researchers across the country described the same practical problem: projects that were “next in line” for funding, hiring, and launch suddenly felt stuck in administrative limbo.

Imagine a familiar version of that moment. A pediatric cancer researcher has spent more than a year designing a study, building partnerships, and preparing a clinical pipeline. A grant application clears peer review. Staff are lined up. Families are waiting for timelines. Then the next email is not an award notice, but a pause and a promise of “policy review.”

This is not just about one lab or one disease. It is a collision between political decision-making and something most people do not think about daily: the basic infrastructure of how humans learn about the world.

Which raises a question that suddenly feels urgent:

What actually is scientific research, and what happens when it stops?

The Problem: We Use the Results, But We Don’t See the System

Most people encounter science as a finished product.

A drug works. A bridge stands. A phone connects. A weather forecast warns you before the storm.

But we rarely see what created those things: the multi-year process of testing, failing, retesting, publishing, and peer critique that turns guesses into knowledge.

That invisibility matters now because what can be paused or cut is not just “research funding.” It is the slow, expensive, unglamorous machinery that tells us what is real.

How Did We Get Here? A Very Short History of Why Governments Fund Research

For most of human history, scientific investigation was often done by wealthy individuals or by universities with private endowments.

That changed sharply in the mid-20th century, when governments learned that organized, publicly funded research could produce breakthroughs that no individual or single company would fund alone, either because the timeline was too long, the risk too high, or the benefit too diffuse.

After World War II, the U.S. government built institutions designed to fund science before anyone knew what it would be useful for:

- The National Science Foundation (1950)

- A major postwar expansion of NIH funding and capacity through the late 1940s and 1950s

- DARPA (founded in 1958 in response to Sputnik)

The logic was simple: some knowledge has enormous value, but no immediate customer.

Examples:

- mRNA vaccine technology, supported by decades of research and public investment long before COVID-19

- GPS, initiated as a civil and military program and developed under the U.S. Department of Defense, before becoming a global civilian utility

- The internet’s foundations, including ARPANET, were funded by ARPA (now DARPA) beginning in the 1960s.

None of these would exist if funding required a short-term business case.

But this model, patient public investment in uncertain outcomes, has always had critics. Some argue it is wasteful. Others say it crowds out private innovation. Still others believe it gives unelected experts too much control over national priorities.

Those debates predate the current moment. But they explain why this funding is politically vulnerable, and why disruptions can feel sudden even when the arguments are old.

What Scientific Research Actually Is (And Why It Takes So Long)

Here is what most people do not realize:

Science is not a single activity. It is a process with stages, each necessary, most invisible.

Stage 1: Basic Research (No Application in Sight)

A biologist studies how a specific protein folds.

A physicist examines the behavior of electrons in a new material.

A chemist investigates why certain reactions happen at different temperatures.

None of this has a product attached. It is pure “how does this work?”

Why it matters: This is where future treatments, materials, and technologies come from, often decades later.

Example: CRISPR, now a foundational tool in gene editing and explored in many disease contexts, traces back to work on bacterial immune systems that defend against viruses.

Stage 2: Applied Research (Turning Findings Into Tools)

Once basic research reveals a mechanism, applied researchers ask: “Can we use this?”

This is where:

- Lab findings become drug candidates

- Material properties become engineering specs

- Theoretical models become testable technologies

Why it’s expensive: Most candidates fail. A drug that works in animals might be toxic or ineffective in humans.

Example: A widely cited rule of thumb is that only about 1 in 5,000 compounds that enter early preclinical testing ultimately become an approved drug.

Stage 3: Clinical Trials and Real-World Testing

Even after a drug or technology shows promise, it must be tested in humans, slowly and carefully.

Phase I: Is it safe?

Phase II: Does it work in small groups, and how?

Phase III: Does it work in larger, diverse populations, compared with standard care?

These phase distinctions, and their purpose, are central to the FDA’s described drug development process.

This process often takes a decade or more from discovery to approval.

Why it can’t be rushed (safely): History is full of treatments that seemed safe or revolutionary until larger trials or longer follow-up revealed serious risks. Fenfluramine/dexfenfluramine (fen-phen) was associated with heart valve disease and was withdrawn in 1997. Vioxx (rofecoxib) was withdrawn in 2004 after evidence of increased cardiovascular risk.

The slowness is not just bureaucracy. It is the cost of not harming people.

Stage 4: Peer Review and Replication

Before findings are accepted, they are scrutinized:

- Submitted to journals where experts review methods

- Replicated by independent labs

- Debated at conferences

This is how science corrects itself over time. And it is why science can look uncertain in public, even when it is working as designed.

Who Pays for This — And Why That Matters

There are three main funders of research:

1. Federal Government

NIH is the largest public funder of biomedical research in the world. Federal agencies fund and perform research across fields, including health, energy, defense, and basic science.

2. Private Companies

Businesses are the largest performers of R&D in the U.S. in dollar terms. For example, the National Science Board’s indicators report estimates that in 2022, the business sector accounted for approximately 78% of U.S. R&D.

But private R&D is heavily shaped by product timelines, intellectual property, and expected returns.

3. Universities and Nonprofits

Universities train researchers, host infrastructure, and publish findings, often supported by federal grants.

A reality check on the mix: In 2021, the U.S. spent about $119B on basic research, $146B on applied research, and $540B on experimental development. Those categories matter because different funders tend to specialize in different parts of the pipeline.

Here’s the Critical Thing Most People Don’t Know

Private companies rely on publicly funded basic research.

NIH-supported research is associated with the published science behind nearly all new drugs approved over extended periods, even though industry typically finances the late-stage development and commercialization.

This is not a moral claim. It is a description of how the system works.

And it is why disruptions to public science funding and processes can echo outward for years.

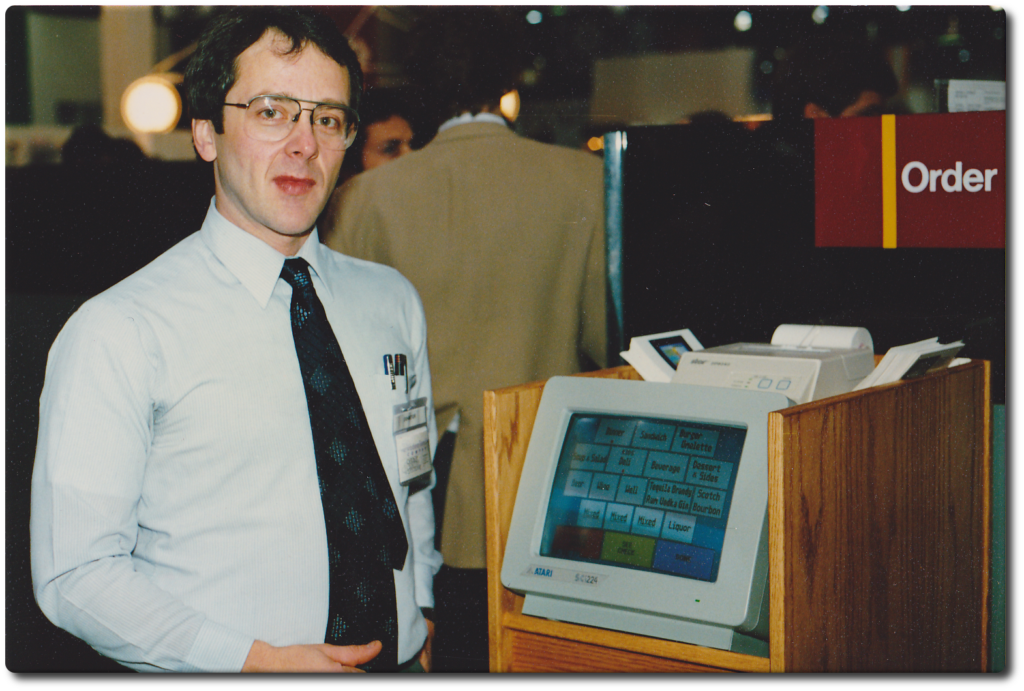

One way to see it is to look at consumer tech. Touchscreen interfaces, for example, emerged through decades of engineering and research, including early work in the 1960s and 1970s and later refinement and mass commercialization by companies.

When public support weakens, private companies do not automatically fill the gap, because they were never set up to fund large amounts of long-horizon, open-ended basic research in the first place. The funding mix has been shifting for years, including a decline in the federal share of basic research funding since 2013.

The Consequences (What Actually Breaks)

When research funding stops or slows, the damage is:

- Slow

- Invisible

- Compounding

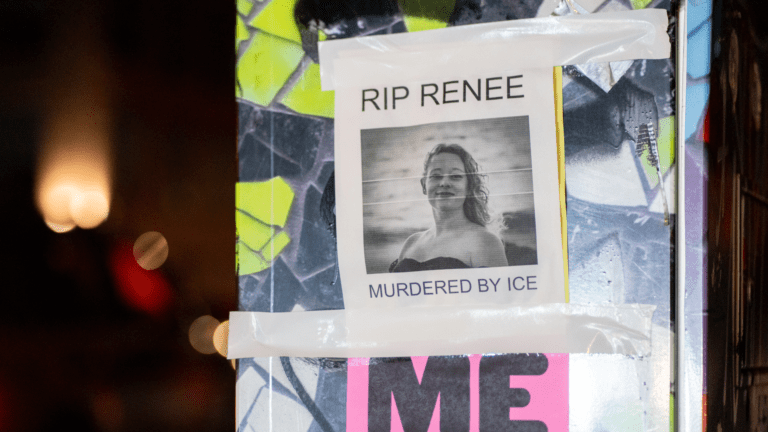

1. Human Capital Drains Away

Graduate students leave for industry.

Postdocs abandon academic careers.

Early-career researchers move to other countries.

Even if budgets later recover, rebuilding teams and specialized capacity is hard, and it takes time.

2. Research Pipelines Freeze

Studies that take years to complete get abandoned mid-stream.

Longitudinal data becomes far less valuable if interrupted.

Example: The Framingham Heart Study began in 1948 and has helped define core cardiovascular risk factors. It is a reminder that some of the most important knowledge arrives only because the work continues for decades.

3. Collaboration Networks Collapse

Science today is global and interdisciplinary.

When U.S. funding becomes unpredictable, international partners can seek more stable arrangements elsewhere.

4. Private Industry Loses Its Seed Corn

Without basic research, the pipeline of future innovations dries up, not immediately, but years later.

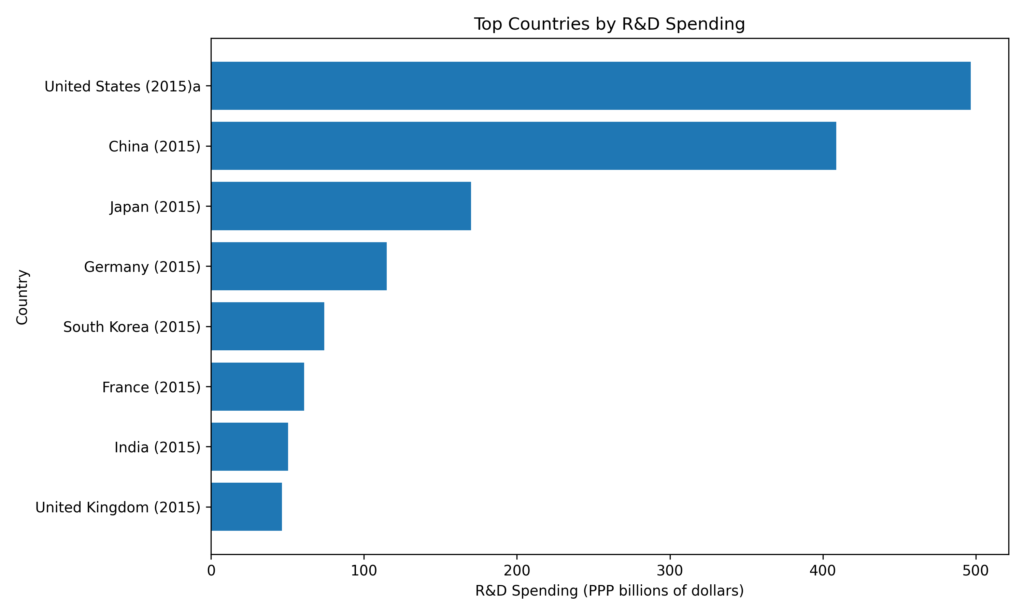

Meanwhile, global competition is real. The United States remains the largest national performer of R&D by internationally comparable measures, but China is close behind and growing rapidly.

5. Public Trust in Expertise Erodes

When research becomes visibly politicized, scientists face an impossible choice:

- Stay quiet and lose public confidence

- Speak up and be labeled activists

Either way, the public increasingly sees research as just another interest group.

Where Things Stand Today

As of January 2026, the situation was fluid, and reporting emphasized process disruptions more than a single clean “funding off” switch.

Some facts were clear:

- HHS imposed a communications and document-release pause that explicitly applied to NIH.

- NIH meetings and grant review-related activity were disrupted or delayed, with reporting tying delays to procedural requirements such as Federal Register notices.

What remained unclear in that moment:

- How long would the disruption last?

- Which projects would resume first?

- What criteria would shape future funding decisions?

What was clear is that researchers were making real decisions under uncertainty.

Some were:

- Seeking opportunities abroad.

- Trying to bridge gaps with private or philanthropic funding (when possible).

- Pivoting away from longer-term projects toward safer, shorter studies.

Each of those decisions is rational for the individual and damaging to the system.

Why This Matters Beyond Research Labs

Here is what is at stake, beyond any one field:

1. National Security

Defense capability depends on advances in materials, computing, biology, and more, which are often seeded by long-horizon research. DARPA’s origin story exists precisely because the U.S. did not want to be surprised technologically again.

2. Economic Competitiveness

Whole industries rest on foundations built over decades. The U.S. remains a leading R&D performer, but leadership is not automatic, and the balance of global investment is tightening.

3. Public Health Preparedness

The next pandemic, the next antibiotic-resistant superbug, the next chronic disease wave will require tools that do not exist yet.

Those tools come from research happening now, or they do not exist when needed. The long arc behind mRNA vaccines is a recent reminder.

4. The Social Contract Around Expertise

For science to work, the public must trust that research is done honestly, that results are not politically predetermined, and that expertise is earned.

When funding and process become visibly ideological, that trust fractures. And once lost, rebuilding it can take far longer than a budget cycle.

Competing Explanations (Why Some Support These Cuts)

It is worth understanding the arguments in favor of reducing federal research support, because they are not all made in bad faith.

Argument 1: Government funding distorts research priorities.

Grant culture is real. It can reward safe, incremental projects and heavy proposal-writing.

Response: That is a reason to improve incentives and review systems, not to collapse the pipeline.

Argument 2: Private industry can fund what’s truly valuable.

If research has real-world value, companies will fund it.

Response: This ignores the time-horizon problem. The parts of research that are most foundational often have the weakest immediate business case. The historical role of public investment in basic research is precisely to cover that gap.

Argument 3: Federal research has become ideologically captured.

Some argue that certain fields produce conclusions that align with political preferences.

Response: This is hard to adjudicate in the abstract. The better answer is stronger transparency, replication, and methodological rigor, not blunt defunding. Cutting funding does not fix bias; it just reduces the production of knowledge and the ability to test claims in the first place.

What Happens Next (Several Scenarios)

Scenario 1: Funding and reviews resume with minor changes

Delays ease, priorities shift slightly, and researchers adapt.

Damage: Real but limited, including lost time, missed hiring windows, and some talent loss.

Scenario 2: Funding becomes explicitly ideological

Certain topics are deprioritized or defunded based on politics.

Damage: Severe. The strongest researchers have options, and global collaboration routes around instability.

Scenario 3: Long-term decline in federal research investment

Funding stagnates while competitors increase investment.

Damage: Slow and invisible, until a crisis reveals the gap.

A Larger Question

What is happening is not just about science.

It is about whether democratic societies can make long-term investments in uncertain goods.

Research is expensive. It is slow. It often fails. Its benefits are diffuse, spread across the whole society.

That makes it vulnerable.

When budgets are tight, it is easy to cut.

When politics are polarized, it is easy to weaponize.

When outcomes are distant, it is easy to ignore.

But the things it produces, vaccines, materials, technologies, and understanding, are what separate modern life from the alternative.

The question is not whether we can afford to fund research. It is whether we can afford not to, and whether we are willing to wait 20 years to find out we made the wrong call.