How a Surveillance State Gets Built: Palantir, ICE, and Your Private Data

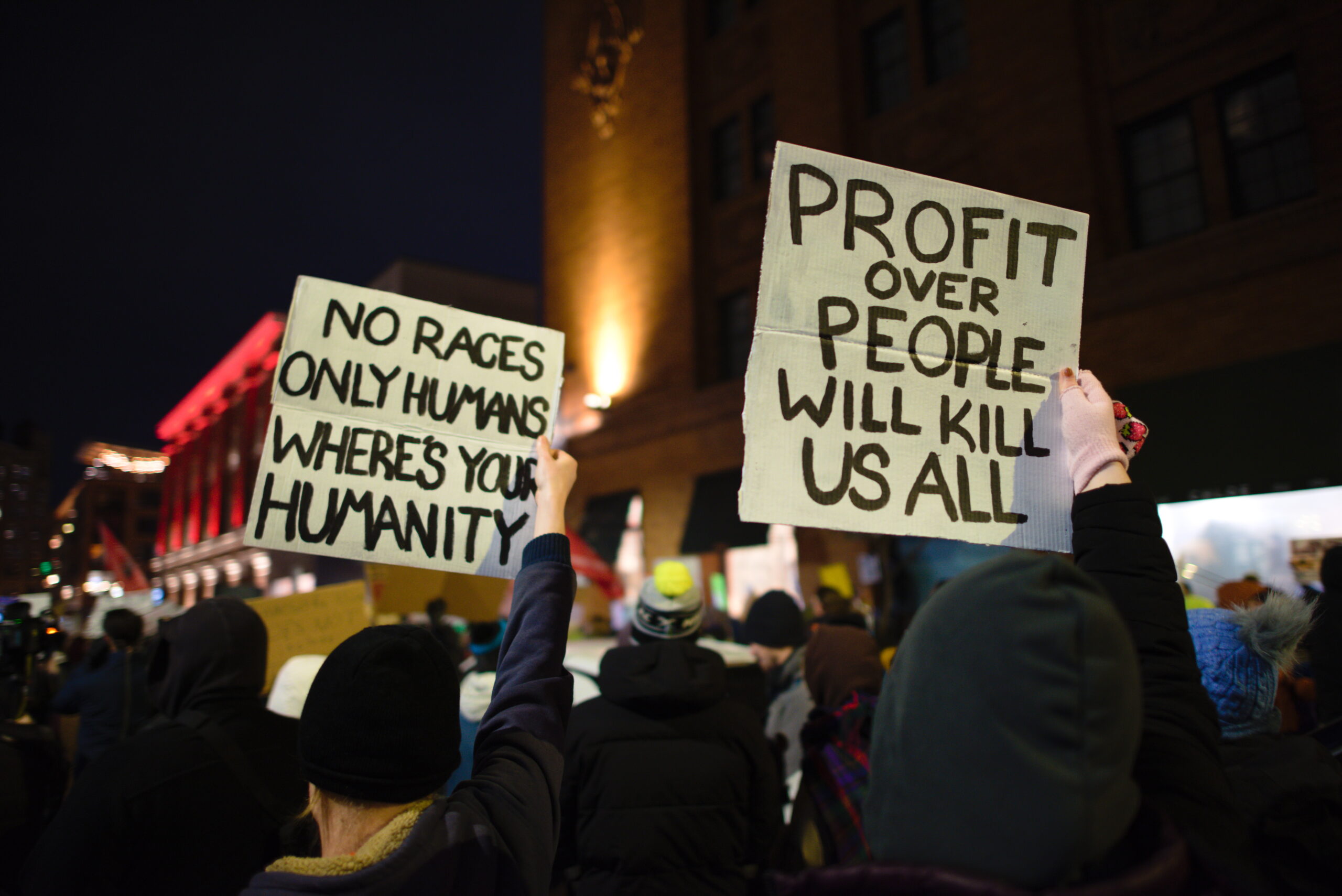

Your private data was never meant to become a map to your front door, but that’s what happens when government power meets private-corporation tooling built for speed and scale. Palantir helps ICE stitch together ordinary records, turn them into searchable profiles, and move those profiles through workflows that end in targeting and arrests, often far beyond the “worst of the worst” story the public gets sold. This is how a surveillance state gets built: not with one dramatic law, but with quiet integrations, automated triage, and systems that make the next knock easier than the last. The question isn’t whether the technology is impressive, it’s what it makes possible.

The knock

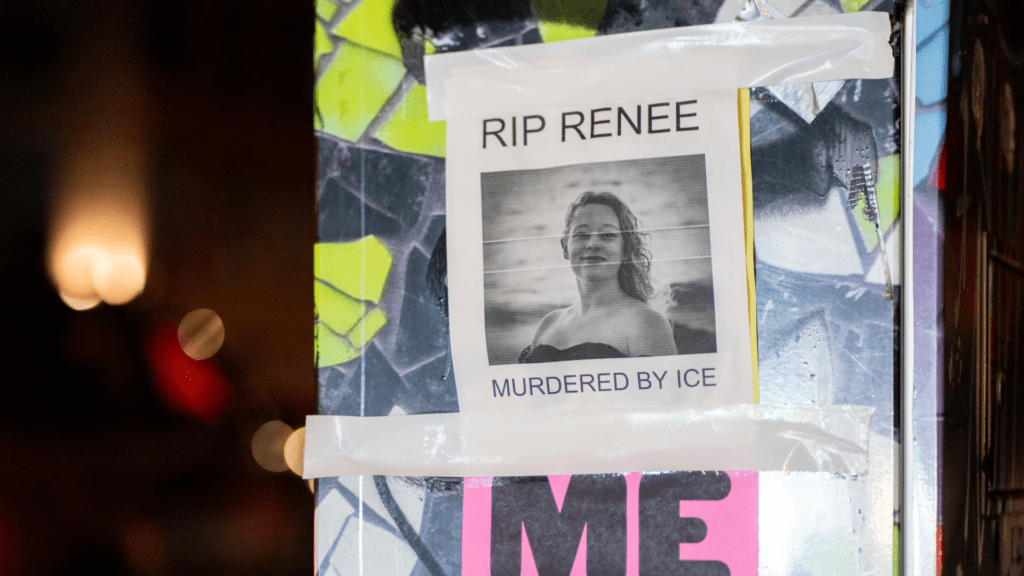

A woman in Chicago checks her phone and sees a missed call from a blocked number. At work, a coworker mentions that “someone was asking questions.” At the grocery store, she hears that an unmarked SUV has been circling the block. She starts to replay every form she has ever filled out, every address she has ever written down, every “normal” interaction with a hospital, a school, a benefits office, a DMV. By dinner, she is rehearsing what to say if a knock comes. Now she’s a “target.”

Not because she is violent. Not because she is hiding in some criminal underworld. Because in 2026, a knock can be the last link in a chain that starts with your private data being stitched together in ways you never agreed to, then routed through software built to turn information into action.

One of the companies most associated with that chain is Palantir.

And one of the agencies it supports is ICE.

That is the human reality sitting behind a very cold sentence you can find in federal contracting language: ICE expects to buy its Investigative Case Management system from Palantir on a sole-source basis.

If you have never heard of Palantir, that sentence will not land the way it should.

So let’s slow down.

What is Palantir

Palantir is a software company that specializes in making lots of messy data usable fast.

Most large organizations store your information in separate systems that do not talk to each other. Different databases. Different formats. Different rules.

Palantir builds platforms that can pull those systems together, so an investigator can search across them, see relationships, and turn your data into a workflow that ends with a decision.

The power of Palantir’s products is not one dramatic feature. It is the way the software makes it easier to connect dots at scale.

And with ICE, “scale” is the point.

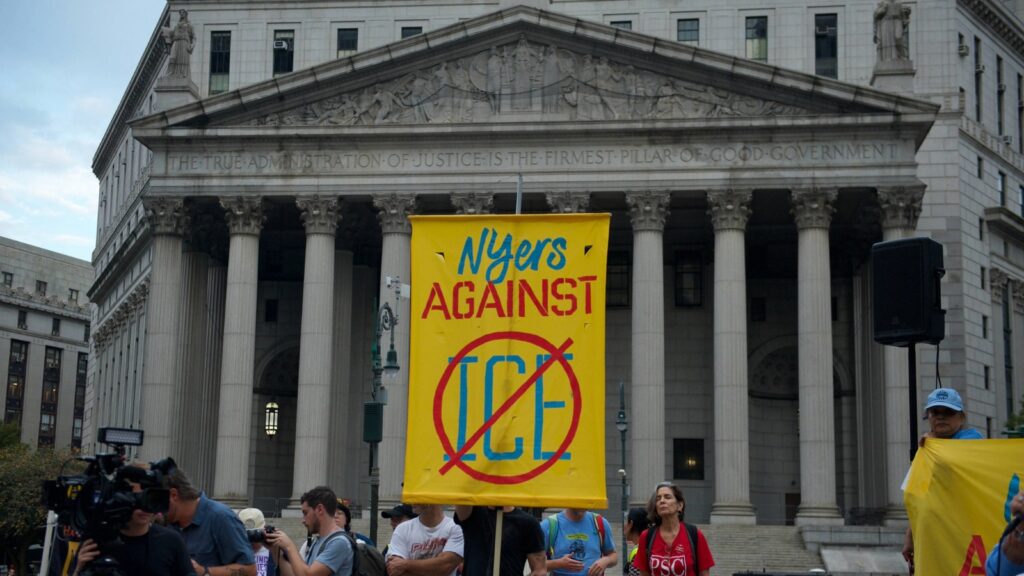

How Palantir connects to ICE

First of all, ICE is not one unit. Two parts matter here:

- HSI (Homeland Security Investigations): investigative work, often with broad law-enforcement data access.

- ERO (Enforcement and Removal Operations): detention and deportation operations

That distinction matters because the knock usually comes from the operational side, but the “case file” can be built across many systems.

Palantir has been tied to ICE for years, but several recent disclosures make the relationship clearer and more consequential.

1) The case management “hub” of ICE work

ICE’s Investigative Case Management (ICM) system is, essentially, the agency’s internal case hub. It is where leads become cases, and cases become operations.

In January 2026, a federal notice said ICE “anticipates” procuring the ICM solution from Palantir on a sole-source basis.

Sole-source means the government is signaling, in effect, that it sees one vendor as uniquely positioned to run a core system. That is how a private company becomes embedded in the daily muscle memory of state power.

Why you should care: case management is not a side tool. It’s the operating system for enforcement. When one vendor sits at the center of that workflow, it’s no longer just “software.” It becomes infrastructure.

2) “ImmigrationOS”

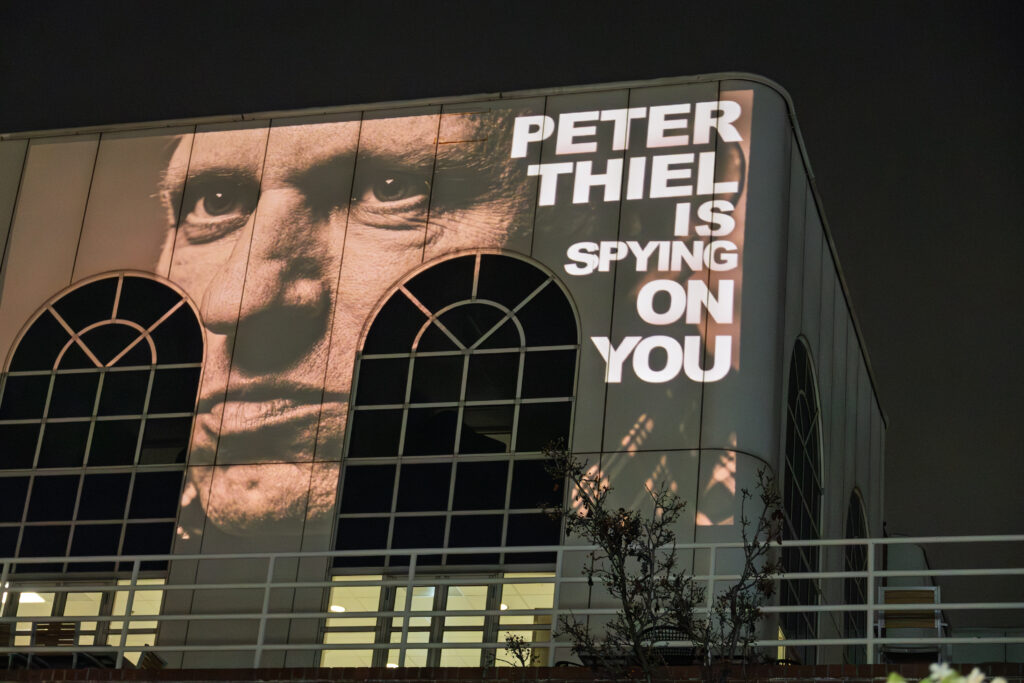

Advocacy and policy reporting describe a Palantir-built platform often referred to as ImmigrationOS, connected to ICE enforcement operations.

It’s the kind of system that can pull together where you’ve lived, who you’ve lived with, what IDs you’ve used, and which databases mention you, then rank you for attention.

The American Immigration Council reported ICE planned a prototype in 2025, with the contract running through September 2027, and described it as using AI and data mining to identify and track people.

Wired previously reported that ICE was paying $30 million for “ImmigrationOS,” aimed at giving ICE “near real-time visibility” on people and helping prioritize deportation targets, based on a contract justification document.

A January 2026 letter from Sen. Mark Warner to the DHS Inspector General references ICE entering a contract with Palantir to upgrade ICM to include ImmigrationOS, describing ICM as having access to information “from across the federal government.”

This is the “your private data” piece that people miss. It’s not only border encounters or criminal cases. It’s the broader reality that once an agency can fuse datasets, everyday interactions can become signals.

3) The tip line: when suspicion gets automated

Now connect the system to the most human, messy thing imaginable: rumors.

In late January 2026, Wired reported that ICE has used an AI-powered Palantir system to summarize tips sent to an ICE tip line since “last spring,” citing a newly released Homeland Security document.

That matters because tip lines are messy by nature. They include real leads, but also misunderstandings, malicious reports, and personal vendettas.

If an AI system is creating “high-level summaries” and triaging urgency, it can shape how a person is framed before a human even looks closely. A summary that flattens nuance is not harmless when the outcome can be arrest, detention, or removal.

Even if the intent is “efficiency,” the cost of being wrong is not a customer-service headache. It is a knock on the door.

The “worst of the worst” story, and why it collapses in practice

The crackdown messaging is often sold as targeted. Violent criminals. “The worst of the worst.” The implication is that ordinary people who are undocumented, or people who are immigrants with complicated status, should not worry.

But real-world reporting keeps colliding with a different reality: enforcement expands, categories blur, and “arrest” gets used as a rhetorical stand-in for “dangerous.”

An AP report on a recent ICE operation in Maine described ICE portraying the effort as targeting the most dangerous people, while court records and legal challenges indicated that some detainees had no criminal record or faced minor issues, and attorneys criticized the way enforcement messaging conflated arrests with convictions.

Once you add quotas, throughput pressure, and a toolchain designed for speed, the promise of surgical targeting was always going to fail.

Systems don’t drift toward restraint on their own. They drift toward what they are optimized to do.

The argument Palantir makes, and why it doesn’t solve the problem

Palantir, and its defenders, tend to argue a few things:

- The tools are used “lawfully.”

- There are access controls and audit logs.

- They are not building a single national surveillance database.

Reuters reported CEO Alex Karp defending Palantir’s surveillance technology by emphasizing built-in safeguards, controlled access, and audit capabilities. Palantir has also published posts pushing back on claims from civil liberties groups and media reporting, framing criticism as misunderstanding what its tools do and how they’re governed.

Some of those points may be true in isolation. But the problem is bigger than the checklist.

The core issue is whether the state has built a practical capability for continuous, scalable targeting (surveillance state infrastructure), with the public largely locked out of how it works.

Because even a perfectly “audited” system can still produce a surveillance state outcome if:

- the data feeding it is too broad

- the enforcement mission keeps expanding

- the public cannot see how the system prioritizes people

- the penalties for error are brutal

- the oversight is too weak, too slow, or too politically constrained

An audit log doesn’t comfort you when the knock is already at the door.

The bottom line

Palantir is not just “helping ICE with software.” It is helping ICE turn data into action faster and, in some cases, automating parts of the pipeline that decide who becomes a “target” and how they are framed inside the system.

In a democracy, the most dangerous upgrades are often the ones sold as efficiency. They feel administrative. They arrive quietly. Then one day, a knock that should have required careful human judgment arrives a little faster, a little more confidently, and with a case file that already looks finished.

This is how that knock starts to feel less like a legal system and more like an algorithm with a badge.