Why The Economy Feels Broken: It’s Over-Financialized

How over-financialization quietly turned homes, jobs, and even hospitals into “assets,” and why it’s hollowing out the real economy

A couple in their thirties sits at a kitchen table, staring at three numbers that do not fit together: the price of the starter home, the monthly payment, and the life they are trying to build. The house is not a place to live. It is a “yield.” A “door.” A line on a spreadsheet. In the background, a mortgage broker pitches rate locks, a lender pitches points, and an investment fund pitches the neighborhood itself. Somewhere between the open house and closing day, the American dream becomes a financial instrument.

That is the feeling of over-financialization: when finance stops serving the economy and starts feeding on it.

Finance is supposed to be the plumbing. It moves savings to productive investment, helps families smooth shocks, and spreads risk so businesses can take real-world bets. But in recent decades, the U.S. economy has drifted toward something else: an economy where profit increasingly comes from extracting fees, interest, spreads, and asset-price gains, rather than from making better goods, building new capacity, or improving services.

Economists have a straightforward definition for financialization: “the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economies.” The over- part is the warning light: when the financial sector becomes so large and so dominant that it starts to slow growth, amplify inequality, and pull talent and corporate attention away from the real economy. The IMF’s research has even framed it in threshold terms, arguing there can be “too much” finance, with credit expansion beyond certain levels no longer helping growth and potentially hurting it.

This is not an argument against banks, markets, or investing. It is an argument against an economy organized around financial extraction.

What over-financialization looks like in daily life

Overfinancialization is when finance grows so dominant that profits increasingly come from fees, debt, and asset trading instead of producing goods and services, weakening the real economy.

Over-financialization is not just about Wall Street traders. It shows up as:

- Housing as an asset class first, shelter second. When investors and financial products treat homes like rent streams and tradeable assets, prices and rents can decouple from local wages.

- Debt as a business model. Household debt has climbed to staggering levels, with the New York Fed reporting total U.S. household debt at $18.8 trillion in Q4 2025.

- Public companies run like portfolios. Executives are rewarded for stock price performance, often measured quarterly, which pushes strategies that boost share price quickly, even when they undercut long-term capacity.

- Services optimized for margins, not outcomes. In sectors like health care, private equity ownership has been associated in multiple studies with changes in staffing and measurable shifts in outcomes, fueling concern that the “financial playbook” is damaging patient care incentives.

Over-financialization is what happens when the rules of finance become the rules of everything.

How we got here: a brief, very American story

1) Deregulation and consolidation changed the shape of finance

Starting in the late 20th century, policy choices helped finance expand in scale and complexity. One symbolic pivot was the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999, which eased barriers between commercial banking, investment banking, and insurance and encouraged large-scale financial integration.

This did not “cause” over-financialization by itself, but it reinforced a direction: bigger institutions, broader financial activities, and a system more intertwined with capital markets.

2) Shareholder value became the corporate north star

The modern public company increasingly treats itself like a financial asset whose primary job is to maximize returns to shareholders. One turning point that matters more than most people realize is the normalization of stock buybacks.

The SEC’s Rule 10b-18, adopted in 1982, created a safe harbor for issuer share repurchases, making buybacks easier to execute without manipulation liability when certain conditions are met. From there, buybacks steadily became a dominant method of returning cash to shareholders.

Before 1982, buybacks weren’t categorically “illegal,” but many companies avoided open-market repurchases because the manipulation risk was real and the rules were unclear; Rule 10b-18 made them much safer and more common.

By late 2025, buybacks were still enormous. S&P Dow Jones Indices reported S&P 500 Q3 2025 buybacks of about $249 billion. And reporting in recent years has described shareholder returns at record scale, with buybacks often the largest component.

Buybacks are not automatically bad. Sometimes they are a sensible way to return excess cash. The problem is what happens when buybacks become a default strategy, even when companies are underinvesting in workers, resilience, R&D, or long-term expansion.

3) The financial sector grew faster than the rest of the economy

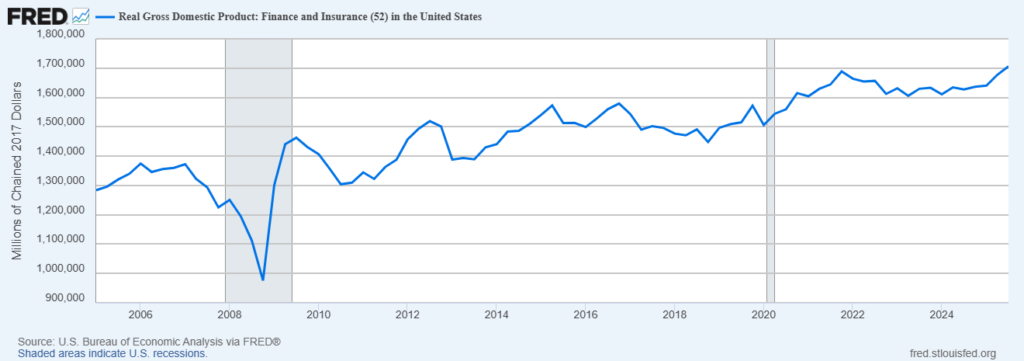

A widely cited line from research on the growth of finance is that the financial sector’s footprint expanded dramatically over the post-war period, peaking at levels that would have been hard to imagine mid-century. Harvard Business School’s Greenwood and Scharfstein note that finance’s measured contribution to U.S. GDP rose markedly over decades, reaching about 8% in 2007 (versus under 5% in 1980).

Even after the 2008 crisis, finance remains structurally central to the economy, and current measures of finance-and-insurance value added are still enormous in absolute terms.

As of Q3 2025, finance alone is about 8% of U.S. GDP, roughly comparable to manufacturing and to education/health combined, and the broader FIRE complex (Finance + insurance + real estate + rental/leasing) is about 21.7% of GDP.

4) The “everything market” made wealth feel like productivity

As more retirement assets flowed into markets (think 401(k)s and index funds) and as households increasingly experienced prosperity through rising asset prices, the economy began to feel like it ran on markets themselves.

This creates a feedback loop:

- Higher asset prices increase household wealth (for those who own assets).

- That wealth fuels consumption and political comfort.

- Policymakers become more cautious about anything that might puncture asset prices.

- Companies lean harder into strategies that support valuations.

It is an economy where the stock chart can feel more “real” than the factory floor.

Why over-financialization is dangerous

1) It pulls money and talent away from productive investment

When high returns are available through financial engineering, fee extraction, or asset flipping, it can be harder for “boring” real-economy investments to compete. The easiest path to hitting earnings targets becomes cost-cutting, leverage, and buybacks.

This shows up as an economy that can appear profitable while becoming brittle.

2) It makes inequality a design feature

If growth is increasingly delivered through asset appreciation, then people who already own assets win first and win most. People who rely on wages feel like they are running uphill, even when the economy is “doing well” on paper.

Over-financialization does not just correlate with inequality. It actively channels income toward capital and away from labor through interest payments, fees, rents, and financial claims on future income.

3) It raises the cost of basics

When the essentials of life become investable streams, the pressure to extract returns can push prices up and quality down. Housing is the clearest example. Health care is another flashpoint, where the private-equity model has raised alarms about staffing, billing, and patient outcomes.

4) It increases instability

Financialized systems tend to be more leveraged, more interconnected, and more prone to cascading failures. That is not a theoretical concern. It is what the 2008 crisis taught, and it is why “too much finance” research focuses on thresholds where credit growth stops helping and starts hurting.

5) It changes what democracy is “about”

This is the quiet civic cost: when large parts of the economy depend on asset prices staying high, policy debates shift. The question becomes less “what improves society” and more “what markets will tolerate.” Over time, public priorities can start to sound like investor updates.

The case for finance, and the honest counterargument

A fair response is that finance can be genuinely productive:

- It can fund startups and innovation.

- It can spread risk and lower borrowing costs.

- It can help households invest, plan, and retire.

All true.

The problem is not the existence of finance. It is the scale, incentives, and political power of finance when it becomes the easiest way to earn money in the economy.

Even the policy response to buyback growth reflects this tension. The U.S. now has a 1% excise tax on corporate stock repurchases (effective for repurchases after Dec. 31, 2022), which implicitly acknowledges that buybacks are not a neutral corporate act when done at massive scale. A 1% tax is small, but the point is what it signals: the concern has entered the mainstream.

What could be done (and what would actually matter)

If we wanted to de-financialize without smashing the plumbing, the most meaningful moves would aim at incentives.

Rebalance corporate incentives

- Tighter rules and transparency around buybacks and executive compensation tied to short-term stock metrics, building on the reality that buybacks are widespread and often used strategically.

- Encourage long-term investment through tax and governance changes that reward retained earnings used for productivity rather than financial maneuvers.

Reduce extraction in essential markets

- Housing: expand supply, limit predatory fee layers, and scrutinize large-scale investor strategies that treat housing primarily as a yield product.

- Health care: enforce transparency and accountability for ownership structures and outcomes where financial strategies can degrade care incentives.

Make credit serve growth, not just balance sheets

- Stronger guardrails against excessive leverage and risk transfer that create “profits now, fragility later,” consistent with the IMF’s warning that finance can pass a point of diminishing returns.

Rebuild the idea of the public interest

This is the hardest part. Over-financialization is not only an economic pattern. It is a cultural one: a society trained to treat asset prices as the scoreboard for everything.

The bottom line

An over-financialized economy can look wealthy while becoming less capable.

It can post strong earnings while underbuilding housing. It can celebrate market highs while families rack up debt. It can turn hospitals, homes, and even public services into revenue streams optimized for extraction.

Finance is necessary. But when it becomes the main way the economy makes money, the economy starts to forget how to make things, how to care for people, and how to invest in the future.

And that is when the plumbing becomes the product, and the rest of us pay the bill.