Why Trump Keeps Coming Back to Greenland, and What It Could Mean

In the first week of January 2026, the idea that once sounded like a punchline snapped back into the “this is real” category. The White House confirmed President Donald Trump and his advisers were again discussing ways to “acquire” Greenland, and said the use of the U.S. military is “always an option” in pursuit of that goal. European leaders and Canada responded with a joint message that “Greenland belongs to its people,” while EU leadership publicly emphasized Greenlanders’ right to decide their own future.

To understand why Trump keeps circling the world’s largest island, it helps to separate three things that are getting mixed together in the public argument:

- Its genuine strategic value in a warming, more militarized Arctic.

- The legal and political reality that the territory is not a tradable asset, and its people have recognized self-determination rights.

- Trump’s personal and political incentives to frame foreign policy as acquisition, leverage, and dominance.

Those three forces point in different directions. And that mismatch is where the danger, and the story, lives.

Greenland is a “location” story before it is a “land” story

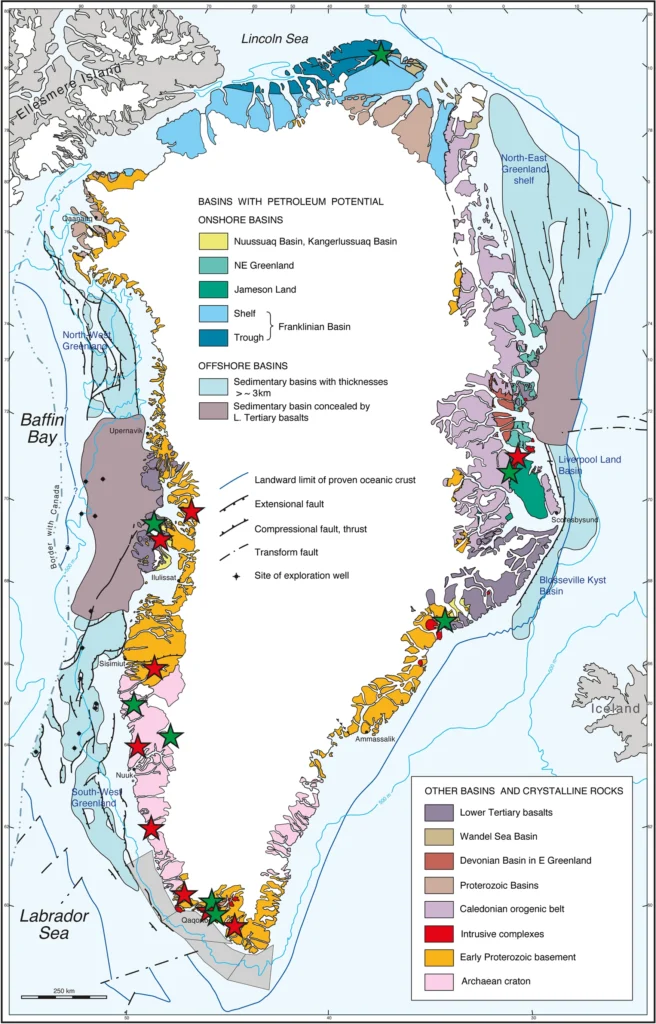

Look at a globe the way a defense planner does. Greenland sits between North America and Europe, on the approaches to the North Atlantic and the Arctic. It is near the Greenland–Iceland–UK gap, a corridor long associated with tracking naval movement between the Arctic and the Atlantic.

The U.S. has treated that geography as strategically relevant for decades, which is why it already has a longstanding defense relationship tied to Greenland. The 1951 U.S.–Denmark Defense of Greenland agreement (and later updates) provides the framework for U.S. defense areas and access, including at what was long known as Thule Air Base and is now Pituffik Space Base.

In the Cold War, this was about early warning and the shortest paths for bombers and missiles. In the 2020s, it is about the same physics with new layers: missiles, sensors, satellites, cyber, and the reality that climate change is making the Arctic more navigable, more commercially tempting, and more contested. The Pentagon’s 2024 Arctic Strategy frames the region as increasingly consequential for homeland defense and cooperation with allies.

If you strip out the theatrics, there is a coherent national security argument that the U.S. should care about Greenland: you can base sensors there, you can monitor air and maritime approaches, and you can coordinate with allies in a region where Russia has invested heavily and where China has sought influence and scientific footholds.

That is the “interest” case. Trump is trying to turn it into an “ownership” case.

The mineral argument is real, but it is also easy to oversell

The White House’s public line, echoed in reporting, is that Greenland matters for both security and resources, including deposits of minerals that matter for high-tech and military applications. Reuters notes those resources remain largely untapped, with real constraints like limited infrastructure and labor shortages.

That resource story fits a broader global reality: supply chains for “critical minerals,” including rare earth elements, have become a strategic obsession for many governments because they feed everything from electronics to defense systems. PBS, in its explainer on Trump’s renewed push, also highlights the territory’s resource potential as part of the “why.”

But “Greenland has minerals” is not the same as “Greenland is a near-term solution.” Mining in the territory is hard: logistics are expensive, permitting is complex, local politics matter, and projects can stall for years. The mineral angle is best understood as a long-term strategic hedge, not a quick win.

This matters because acquisition rhetoric can sound like a shortcut around the slow work of building supply chains, investing in allied mining and refining capacity, and negotiating with Greenland’s government and communities on terms they accept.

The sovereignty problem is not a footnote, it is the whole point

Greenland is part of the Kingdom of Denmark, with extensive self-government. Denmark’s Prime Minister’s Office notes that Greenlanders are recognized as a people with a right to self-determination under international law, and that the Self-Government Act is based on an agreement between Greenland and Denmark “as equal partners.”

In practice, that means Greenland is not “Denmark’s property” to sell in a simple real estate transaction, and it is certainly not something another country can “take” without detonating the legal order that protects borders. Even if Denmark were hypothetically open to a discussion, Greenland’s consent and politics are central.

That is why the most important pushback in this week’s reporting is not just moral outrage, it is the rules-based objection: major European leaders and Canada publicly emphasized that Greenland’s future belongs to Greenlanders, and EU leadership reinforced the same point.

So why does Trump keep returning to it?

Reuters reporting this week captures the basic dynamic: Trump sees acquiring Greenland as a “national security priority,” his team has discussed multiple options (including purchase and even a Compact of Free Association), and a senior official described his preference for “dealmaking,” saying “he loves deals.”

From that reporting, and from how Trump has framed similar issues, you can see a cluster of motivations that reinforce each other:

1) A dominance narrative that plays well in his political style

In Trump’s framing, geopolitical competition is often expressed as control: who “has” what, who “wins,” and who is “strong.” Greenland becomes a symbol as much as a place.

2) A “big, legible” foreign policy move

Arctic security cooperation is technical and slow. Buying an island is headline-sized. It converts a complex policy domain into a single, simple claim: I expanded America.

3) Leverage over allies, and leverage within alliances

Even without an actual deal, the pressure campaign can force Denmark, Greenland, and NATO into urgent conversations about Arctic funding, basing, and investment. That leverage can be the point.

4) The strategic reality he is exploiting is not imaginary

Russia and China are part of why the Arctic has re-entered the U.S. strategic imagination. The difference is that most of the U.S. security establishment talks about access, agreements, and alliances. Trump talks about possession.

In other words, the “obsession” is partly personal brand and partly a bet that the moment is ripe, because the Arctic is changing and great power competition is sharpening.

What could it mean, in practice?

The consequences depend less on what Trump says and more on which pathway, if any, the administration tries to pursue.

Scenario A: More U.S. basing and investment, negotiated normally

This is the least dramatic and most plausible outcome: the U.S. uses the controversy to push for expanded access, more infrastructure, more joint exercises, more sensors, and more investment in Greenland’s economic development, all through agreements with Denmark and Greenland.

That approach is consistent with the existing defense framework and with how allies typically handle strategic geography.

Upside: real security gains with less legal chaos.

Risk: even “normal” expansions can trigger domestic backlash in Greenland if people feel pressured or sidelined.

Scenario B: A Compact of Free Association pitch

Reuters reports that a COFA arrangement was among the options discussed. COFA is a specific kind of relationship the U.S. has with certain Pacific states, involving defense and economic provisions, while the partner remains self-governing.

Applied to Greenland, a COFA pitch would implicitly intersect with Greenland’s long-term independence debate, because it offers a way to deepen U.S. ties without formal annexation. That could attract some Greenlanders who want alternatives to Copenhagen, and repel others who see it as swapping one patron for another.

Upside: creates a structured, negotiated relationship that acknowledges self-rule.

Risk: destabilizes Denmark–Greenland relations and turns Greenland’s independence politics into a proxy contest among larger powers.

Scenario C: “Purchase” talk that functions as coercion

Even if no sale is realistic, repeated “we’re going to get it” messaging can act as pressure. It can chill investment, inflame nationalist politics, and force Denmark and NATO into a reactive posture.

This is already visible in the diplomatic backlash and the public statements of support for Greenland’s sovereignty.

Upside: none, unless the goal is pure leverage.

Risk: long-term alliance damage for short-term theater.

Scenario D: Military threat language becomes a strategic crisis

This is the scenario that turns a dispute into a rupture. Reuters notes that a military seizure would send shock waves through NATO.

Even if nobody believes an invasion is likely, the act of normalizing that language against an ally changes what other states assume about U.S. commitments. Deterrence works on credibility, but so does trust. You can erode one while trying to project the other.

Upside: none that does not come at an extreme cost.

Risk: NATO cohesion, international legal norms, and U.S. global legitimacy.

The deeper stakes: Greenland’s future, not America’s fantasy

There is a tendency in U.S. coverage to treat Greenland as an object in someone else’s drama. The better lens is that Greenland is a society with its own debates: about economic development, environmental tradeoffs, and long-term independence. The international reaction this week keeps returning to the same principle for a reason: whatever happens has to run through the consent of Greenlanders.

If Trump’s fixation has one paradoxical effect, it may be to accelerate Greenland’s search for leverage, whether that means more autonomy within the Kingdom of Denmark, a faster independence timetable, or a new balance among Denmark, the U.S., and other partners.

But that is not a deal to be “won.” It is a political future to be chosen.