America’s Public Media Is in Crisis — What We Lose If Local Stations Go Dark

Public media has long been one of the most trusted pillars of American civic life, providing everything from Sesame Street and Tiny Desk Concerts to emergency alerts, local investigations, and essential reporting in communities commercial outlets rarely reach. But over the past year, the entire system that underpins this network of radio and television stations has come under severe threat.

In the summer of 2025, Congress eliminated $1.1 billion in previously approved federal funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), a move that experts warn could lead to the closure of more than a hundred local stations by mid-2026—many in rural, remote, or tribal regions where public media is the only reliable source of news.

This is the story of why public media matters, how deeply embedded it is in American communities, and what is at stake if these cuts go unaddressed.

A National System Built to Reach Everyone

Nearly all public media in the United States operate under the CPB, which distributes federal funding to more than 500 radio and TV grantees representing over 1,500 local stations. Together, they reach nearly 99% of the U.S. population with free programming and essential services. The impact of public media has always extended beyond entertainment; it has pioneered accessibility tools such as closed captioning in the 1970s and consistently provided programming in languages including Haitian Creole, Navajo, and Vietnamese.

These contributions sit on infrastructure deliberately designed to be independent of political influence. When President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967, he emphasized that public media should offer the best in music, theater, and reporting while remaining free from government or party control. To achieve that, the CPB was established as a private, nonprofit corporation—one supported by federal dollars but protected from federal editorial interference.

Yet from its inception, CPB’s annual funding has been dependent on the congressional appropriations process. That dependence has made public media chronically vulnerable to political pressure, and over the past five decades lawmakers have repeatedly attempted to slash budgets, often justified by accusations of ideological bias.

A Long History of Political Attacks

Public media’s first major threat came just two years after the CPB was formed. The Nixon administration attempted to cut the corporation’s funding in half, citing the financial strain of the Vietnam War. That effort prompted the now-legendary testimony of Fred Rogers, who told a Senate committee that public television allowed children to understand their feelings, learn empathy, and recognize their own self-worth. His testimony convinced lawmakers to preserve funding at the time.

But the political pressure never truly relented. Decade after decade, critics—largely on the political right—have argued that NPR and PBS reflect a liberal cultural bias, despite evidence that much of public media content is locally produced and heavily community-focused. These criticisms often rely on out-of-context examples, and hearings in recent years have featured lawmakers misinterpreting individual segments or misunderstanding the purpose of local programming. Nonetheless, such arguments directly shaped the 2025 vote to eliminate CPB funding entirely.

What the Funding Really Supports

One of the central misconceptions about public media is that federal dollars flow primarily to national brands like PBS and NPR. In reality, more than 70% of CPB funding goes directly to local radio and television stations. These stations use the money to:

- Produce local news

- Purchase equipment

- Maintain broadcast towers

- Acquire national programs such as PBS NewsHour or All Things Considered

While on average federal funds represent 14–18% of station budgets, these averages mask enormous disparities. Wealthier urban stations can survive modest reductions—for example, WNYC in New York would lose only about 4% of its annual budget. But stations serving rural, remote, or tribal regions are far more dependent. KLND in McLaughlin, South Dakota, lost half its funding. KSHI on the Zuni Pueblo in New Mexico lost 96%.

In these environments, CPB support is not supplemental—it is existential.

Without federal dollars, many stations will be forced to reduce local reporting, cut staff, scale back emergency alerts, or shut down entirely. Ironically, those cuts will push stations to rely more heavily on the national programming critics claim they oppose, because producing original local journalism is the most expensive part of operating a station.

Local Public Media: A Lifeline for Communities

Public media fills critical gaps left by commercial outlets—gaps that are especially acute in rural and low-income areas. In many places, stations offer services that literally no other institution provides.

Community Announcements and Hyperlocal Information

At a Colorado station, daily public service announcements inform residents of school supply distribution events, community meetings, free meals for veterans, and other local happenings. These are often the only timely notices available to residents.

High School Sports

Public television in states like Arkansas broadcasts high school sports—programming beloved by families but not profitable enough for commercial networks to produce.

Marketplace Exchanges and Community Culture

Some stations run programs like “Trading Time,” a Northern California call-in show where residents sell or trade items live on air. These quirky, hyperlocal features strengthen community identity and preserve forms of civic interaction that are disappearing nationwide.

Local Journalism and Investigations

Public media stations consistently break stories that commercial outlets overlook:

- In West Virginia, local public stations exposed that a prominent coal executive who opposed black lung protections later filed for black lung benefits for himself.

- In Alaska, KTOO uncovered a widespread food stamp processing backlog affecting thousands of residents.

- In New Hampshire, a public radio reporter investigated sexual misconduct allegations at the state’s largest addiction treatment center, continuing her reporting despite being sued, harassed, and targeted with vandalism.

These stories required local reporters who understood their communities and built relationships over time—precisely the kind of journalism that disappears when stations lose funding.

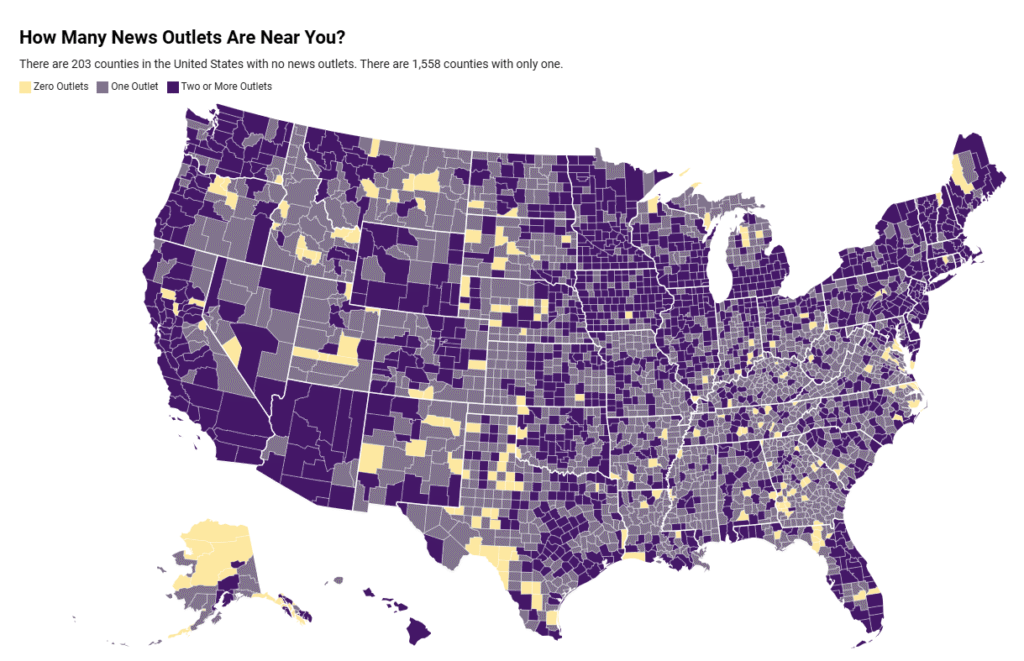

In Some Counties, Public Media Is the Only News

A national analysis found:

- There are 204 counties in the U.S. without any local news outlets.

- In 1,562 counties (50% of counties) in the U.S., there is only one remaining local newspaper, often public broadcasting.

Losing these stations would instantly create dozens of new “news deserts.”

Emergency Broadcasting: The Most Critical Function of All

Beyond entertainment and journalism, public media plays a life-saving role during emergencies. Radio remains one of the few reliable communication methods during hurricanes, floods, and wildfires—especially in regions where residents lack internet, cable, or satellite access.

Louisiana

In Louisiana, where 19% of residents live in poverty and 15% lack internet access, public radio is often the only source of storm warnings and evacuation updates. As one station manager explained: “Radio saves lives. Without it, people would die.”

North Carolina

During Hurricane Helen, Blue Ridge Public Radio—a station with a staff of just seven—broadcast nonstop updates throughout the storm and a subsequent 53-day clean water crisis. Listeners later described the station as their sole source of information.

These examples underscore that public media is not merely a cultural institution; it is emergency infrastructure.

Why the Market Won’t Replace It

Some policymakers argue that private media or the free market could fill the gap left by collapsing public stations. But public media exists precisely because commercial outlets have not found it profitable to provide:

- Rural emergency alerts

- Local government reporting

- Native-language programming

- High school sports

- Hyperlocal community announcements

- Specialized investigative journalism

These services require staffing, expertise, and resources without the commercial return necessary to sustain them.

International comparisons reinforce this point. The United States invests less than $1.60 per capita in public media—far below countries like Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, which invest around $100 per capita. Research consistently shows that strong public media systems correlate with healthier democracies, greater civic participation, and more informed voters.

At a time when American democracy faces unprecedented challenges, weakening one of the nation’s most trusted informational institutions is especially dangerous.

What Can Be Done Now

In a more stable political environment, Congress could adopt long-proposed reforms to insulate CPB funding from partisan appropriations. Ideas have included a permanent tax or a public broadcasting license fee similar to systems used in Europe.

But with no prospect of such reforms being enacted soon, public media’s survival now depends on emergency efforts to fill the funding gap.

Bridge Funds and Emergency Relief

A nonprofit organization, the Public Media Company, has created the Bridge Funds, a national pool dedicated to keeping at-risk stations afloat as long as possible.

Adopt-a-Station

Supporters can donate directly to the stations in greatest jeopardy through adoptastation.org, which lists outlets most threatened by the loss of CPB funds.

Private Philanthropy

Even unusual forms of philanthropy have emerged. Bob Ross, Inc., auctioned three original Bob Ross paintings—raising $662,000 for public TV stations.

The Cost of Doing Nothing

The stakes could not be clearer. Without immediate support, dozens of stations will close, leaving millions of Americans without:

- Local news

- Educational programming

- Emergency alerts

- Community announcements

- Investigative reporting

- Cultural and linguistic programming

- Coverage of local schools, sports, and events

- Systems that connect residents during crises

Public media is more than a broadcaster—it is a civic anchor. Its collapse would accelerate the spread of news deserts, weaken democratic infrastructure, and rob communities of trusted sources of information at a moment when misinformation spreads easily and quickly.

For more than fifty years, public media has given Americans access to accurate reporting, cultural programming, essential warnings, and local stories that no commercial system has ever replicated. If these stations go dark, what disappears is not just the sound of familiar voices or childhood programs, but the informational backbone of entire regions.

This is what the country stands to lose—unless the public decides that public media is worth saving.